Creation and destruction… when the Engineer awakens from his aeonic slumber he immediately re-kickstarts his mission to wipe out humanity.

When Dan O’Bannon was twelve years old he stumbled across an old anthology of stories in a book store. He paid the nickel and took it home. Inside was a story titled The Colour Out of Space, by HP Lovecraft. “I stayed up all night reading the thing, and it just knocked my socks off,” O’Bannon said.

In Lovecraft’s fiction the universe is a source of both awe and terror. Humanity’s dominion over the world is illusory. Revelation is destructive and victory is often paltry, if attainable at all. Humans are beleaguered by demons, devils, minor and major gods, and chthonic beings. Lovecraft would go on to inspire O’Bannon’s creative life, with HR Giger telling Cinefantastique in 1988 that Dan was “definitely one of the greatest Lovecraft experts around.”

In 1979 Giger and O’Bannon brought their own form of Lovecraftian terror to the screen with Alien, which according to Dan, “went to where the Old Ones lived, to their very world of origin … That baneful little storm-lashed planetoid halfway across the galaxy was a fragment of the Old Ones’ home-world, and the Alien a blood relative of Yog-Sothoth.” Whilst Lovecraft’s influence on Alien was expressed as a very palpable undertone, in Prometheus Lovecraft’s notions of alien creators would be embodied further through the daemonic Engineer race.

Both of Lovecraft’s parents were at one point in their lives confined to mental asylums, and the writer himself suffered from frequent bouts of severe illness, semi-invalidism, alienation and eremitism. These difficulties apparently influenced and cemented his dim view of humanity. His fiction married supposedly dichotomous Enlightenment (reason) and Romantic (the irrational) ideals. Most, if not all, of his protagonists are investigators, professors, and scientists who happen to stumble across the Infernal. Other influences included the macabre writing of Edgar Allan Poe and Lord Dunsany; the latter of whom wrote of a slumbering god (Mana-Yood-Sushai) who creates before he sleeps and destroys upon waking, with existence being merely an endeavour to let sleeping gods lie.

Lovecraft’s interstellar gods were no kinder. Arguably at the top of Lovecraft’s hierarchy of gods sits Azathoth and Yog-Sothoth. Azathoth is a being of cosmic immensitude who lies beyond understanding: he is unseen, unspeakable, and ultimately unknowable. In addition to this, he is completely inimical or indifferent towards our existence. Yog-Sothoth, called “the lurker at the threshold,” is equally beyond human scope but, unlike Azathoth, makes contact with humanity, if only to guide their destinies, to demand devotion and worship, and sometimes to breed. Most famous of Lovecraft’s dark gods is of course Cthulhu, the submerged, dreaming god whose inspiration can be drawn back to Dunsany’s likewise sleeping Mana-Yood-Sushai. Though Prometheus’ title and central metaphor points towards Greek myth, it also parallels, perhaps even more strongly, the work of Lovecraft.

“They worshipped, so they said, the Great Old Ones who lived ages before there were any men, and who came to the young world out of the sky. Those Old Ones were gone now, inside the earth and under the sea; but their dead bodies had told their secrets in dreams to the first men, who formed a cult […] hidden in distant wastes and dark places all over the world until the time when the great priest Cthulhu should rise and bring the earth again under his sway. Some day he would call, when the stars were ready…”

~ HP Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu, 1928.

An example: in Prometheus it is revealed that an ancient race of alien beings, the Engineers, inhabited the Earth in its prehistory and were responsible for the creation of its first life-forms. Humanity owes their existence to the Engineers, who created them for reasons unknown. The Engineers also created an amorphous, tar-like substance to manipulate life and death; this substance is deadly, and is essentially a form of bioengineered weaponry. However, the Engineers are ultimately annihilated by their creation. The characters in the film muse on ancient gods who came to Earth to create and instruct mankind for purposes unknown.

In At The Mountains of Madness, it is revealed that an ancient race of alien beings, the Elder Things, inhabited the Earth in its prehistory and may have been responsible for the creation of its first life-forms. Humanity may owe their existence to the Elder Things, who created them to be slaves or playthings or for consumption. The Elder Things also created amorphous, tar-like creatures known as Shoggoth to serve as a slave race; the Shoggoths are deadly, and are essentially a form of bioengineered weaponry. However, the Elder Things were ultimately annihilated by their creations. The characters in the story muse on “Great Old Ones who filtered down from the stars and concocted Earth life as either a joke or mistake.”

The Elder Things & Engineers: one key difference between Lovecraft’s Elder Things and Prometheus‘ Engineers is that, despite being the creators of Mankind, the Elder Things remain completely alien in shape – we were certainly not made in their image. The Engineers by comparison are anthropomorphic.

Both Prometheus and At The Mountains of Madness dispel the notion that Man is a divinely inspired creation. We are not “Creation’s pampered favourites”. Instead, we are simply the experiments of god-like creatures with little interest in our spiritual or physical well-being. If anything, Man is an accident, a mistake, or perhaps even a joke; subject to arbitrary extermination for little or no reason at all.

In At The Mountains of Madness, the expedition team find the remains of their creators, the Elder Things, within the bowels of an Antarctic ruin. Also lurking in the ancient city are the black, amorphous Shoggoth…

In Lovecraft’s The Nameless City the narrator uncovers an ancient pre-human city on the Arab peninsula. “It must have been thus before the first stones of Memphis were laid, and while the bricks of Babylon were yet unbaked.” The narrator enters and deciphers the history of a long-lost civilisation through their remaining murals and hieroglyphics. In the end, this shrieking, apparently human-hating race returns from the bowels of the Earth to snatch him.

Ridley Scott frequently referenced Erich von Daniken, rather than Lovecraft, as an influence on Prometheus, with Lovecraft being an inheritance from Dan O’Bannon’s unfilmed Alien material. It’s somewhat ironic that the work of von Daniken, whose books were referred to as exercises in “sloppy thinking” by Carl Sagan, is purely a pseudo-scientific pilfering of the fiction that Lovecraft jokingly referred to as “Yog-Sothothery.”

In The Cult of Alien Gods: HP Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture, author Jason Colavito writes: “To add a layer of reality to his story, Lovecraft drew on existing pieces of myth and legend as well as the sensational claims of amateur historians and philosophers. Here he threw in a bit of the myth of Atlantis, there a dollop of Theosophical philosophy. He never believed in any of it himself, committed as he was to science, reason, and materialism. However, he recognised that dropping in bits of dark legends made for a sensational story.” Von Daniken also could not resist these same literary flourishes.

Prometheus can also lend itself, interestingly, towards Gnostic creation myth. The Gnostics had a simple solution for solving the problem of evil: the Creator of the world was himself evil, or at least imperfect; not a God, rather a Demiurge. Whilst the Supreme Being (God Itself) exists within the Absolute (the world beyond the tangible), the Demiurge exists in a plane where he is unaware of both the Supreme Being and the Absolute, and concludes that he is the only thing in existence. With this in mind, he creates the physical universe as we know it. Because this Demiurge is not God (though he may consider himself so), his universe is intrinsically imperfect. The Demiurge, essentially, has usurped the name of God. The Engineers can be seen as a race of Demiurges who colonise and seed planets with life, utterly ignorant of their own Creator, or perhaps in defiance of him. These creator-beings seem benign, but as the characters of the movie find out, they are in fact interstellar warmongers with an apparently atavistic tendency towards violence. The Prometheus research crew “find an establishment which is not what they expected it to be,” according to Scott, continuing: “it’s a civilization, but what we find in it is very uncivilized behaviour.”

As we see in Prometheus, the Engineers are not, or were not, annihilators per se. The aptly-named Sacrifice Engineer donates his body to a young planet (not necessarily Earth, according to Scott) and seeds the waters with DNA that presumably goes on to form that particular planet’s first cells and creatures. The notion that “to create, you must first destroy,” is also tied into cyclical creation myths. According to the Rigveda, an ancient Hindu scripture, Creation is unknowable, even to the gods: “Who really knows, and who can swear, how Creation came, when or where! Even the gods came after Creation’s day …”

“It’s everything…”: Whether the Engineer creates all life or simply human life is a muddled and murky affair; it does not make sense biologically nor narratively either way—though the film wants to play at science, it comes completely unarmed; mythology is its stronger suite. Shaw however does note that, “it’s us, it’s everything,” and Arthur Max stated that humanity in particular were further enhanced and modified -made distinct from other life, as it were- throughout Earth’s history post-seeding. None of this is implicit in the movie, however.

Indian mythology posited that the Universe is subject to a constant cycle of death and rebirth. Where Lord Dunsany’s wicked god creates, sleeps, wakes, then destroys, the Hindu conception sees the living Universe as Brahma’s day: when Brahma slumbers/dies, the Universe ends, only to be born again once he awakens/is reborn (reassuringly, Brahma’s day/lifespan lasts many billions of years according to the text).

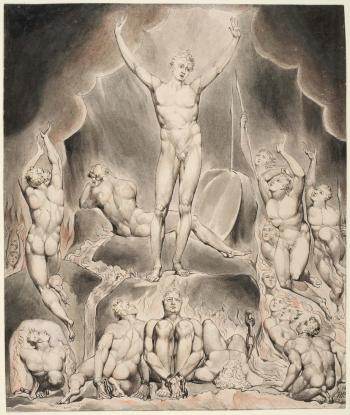

Of course, though a direct line can be traced from the Engineers to Cthulhu to Mana-Yood-Sushai, the parallels to Gnosticism and Hinduism are largely speculative. Ridley Scott himself invoked the fallen angels of John Milton’s Paradise Lost. “If you look at the Engineers,” said Scott, “they’re tall and elegant … they are dark angels. If you look at Paradise Lost, the guys who have the best time in the story are the dark angels, not God.” (The allusion to angels personally evokes the opening line of Rainer Maria Rilke’s The Second Elegy: “Every angel is terrifying …”) Scott drew on the art of William Blake to illustrate the Engineers, along with a dash of Greco-Roman sculpture to suggest nobility, power, and empire. Blake, famously, provided illustrations for Milton’s epic poem, and his images of the Adonic, alabaster-skinned fallen angels were referenced for the unsuited Space Jockeys.

William Blake’s rendition of Milton’s Satan, who is calling upon the other fallen angels to raise their parliament in Hell. “[Ridley] wanted the aspect of the naked Engineer to recall the characters of William Blake’s work,” revealed creature prosthetics supervisor, Conor O’Sullivan. “The other main references for these characters was Michelangelo’s statues, like his famous David.”

Whether the Engineers are genuinely heavenly outcasts or awakened gods is not revealed in the film. Arthur Max, in Prometheus: The Art of the Film, did note that the Engineers “play the role of God in the universe” and “have visited Earth many times over the millenia and given Mankind genetic upgrades, both physical and intellectual.” The Engineers then, with their advanced technology and knowledge of biology, are simply playing at god. Their “upgrades” may settle the debate on why humans are so close to them in physiology, and yet other life from their colonised worlds (dogs, cats, birds, our ape cousins, etc.,) are not. They seed worlds with life and then craft select organisms in their image. Presumably.

When Lord Dunsany learned of the Greek Pantheon, he felt pity “for those beautiful marble people that had become forsaken.” Though mankind had discarded these gods in favour of new ones, in Prometheus it is humanity that is forsaken, and the Engineers strive for unknown cause to destroy us, just as the gods of innumerable mythologies condemned and attempted to destroy mankind before. Whatever their motive, we can ascertain that the Engineer culture revolves around the notion of sacrifice.

“All he’s doing is acting as a gardener in space,” explained Scott when describing the actions of the Sacrifice Engineer in the movie’s beginning. “And the [resulting] plant life, in fact, is the disintegration of himself. If you parallel that idea with other sacrificial elements in history –which are clearly illustrated with the Mayans and the Incas– he would live for one year as a prince, and at the end of that year, he would be taken and donated to the gods in hopes of improving what might happen next year, be it with crops or weather, etcetera.”

The didactic nature of the Space Jockeys as arbitrary creators and destroyers remains the film’s most intriguing element. Though Scott raised the thought that humanity was due punishment for the crucifixion of Christ (a thankfully deleted element) a more haunting prospect could be the proposition that we are due to die for nothing at all, but are merely caught in an impersonal cycle of death and rebirth. To invoke Percy Bysshe Shelley: “Worlds on worlds are rolling ever/From creation to decay/Like the bubbles on a river/Sparkling, bursting, borne away …”

“The primary take away from the myth of Prometheus is that the Gods were nervous about mankind. They were nervous about what they would be capable of if they had fire. Fire was a big piece of technology that they would build off of. And the story of any creation is eventually a child will try to destroy its parents. It’s a very paranoid world view, mythologically-speaking it pops up a lot. Especially for us Star Wars aficionados. So the essential story is: I don’t want to give my kid this toy because eventually he will develop it into a weapon that will kill me. So I will therefore withhold it from him. And what is the price I must exact on somebody who betrays me?”

~ Damon Lindelof. Collider, 2012.

I love your blogs on the Alien series. Please keep them coming!!!

Very interesting read! Thanks! 🙂

Pingback: Gods & Monsters | Strange Shapes

Brilliant! Best trivia site ever.

Thank you very much for this piece.

A very informative article with a lot of little known facts. Thank you for your amazing work.

I feel the decision to move away from a story based on Lovecraft’s works was one of the biggest weaknesses of the film. There were two aspects that made Ridley’s first Alien great: Giger and the script following O’Bannon’s original Lovecratian storyline. When Ridley was named as the director of Prometheus we all assumed that he would bring these aspects back to the Alien universe. Unfortunately, that was not the case…………

Prometheus is patently Lovecraft-ian enough to discourage Guillermo Del Toro from pursuing his own big-screen adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness.

Not sure what Guillermo Del Toro and his misunderstanding of the Lovecraftian influence in Prometheus adds to the conversation but thanks none the less

I didn’t really see any lovecraft in prometheus.

You might see it if you TRIED to see it, the same way you could see almost anything in the haphazard, deliberately blurred goo blot that is prometheus.

Any lovecraftian images or references in prometheus are almost surely either unintentional just from ripping off so much stuff from Alien and its production materials,

or callously tossed against the wall by lindelof while he spent a weekend scouring wikipedia to fill his rewrite with references to random things that he thinks will add up to mime the appearance of intellectual sophistication.

If prometheus is patently anything its patently lindelofian.

Sorry, beyond your first sentence. you are upside-down wrong.

You might NOT SEE it if you TRY not to see it. Apparently you need not to see it. The reason, of course, it’s totally your personal business.

Wow, I was sure till this moment that the film is called Prometeus because the initial ‘sacrificial engineer’ has actually stolen the gift of life from the rest of the pantheon thus his descendants are sentenced to death.

Good stuff. We need more Lovecraftianism in the next Alien/Engineer film.

Pingback: Инженеры Мифов Ктулху • LOVECRAFTIAN

Pingback: Memory: The Origins of Alien

Pingback: Memory: The Origins of Alien | CENSORED.TODAY