Tracing Alien to its origin leads us to many disparate and far-flung places: one is 1940’s Chur, where Hans Ruedi Giger is stumbling upon the museum mummies and dreaming the claustrophobic nightmares that would inspire his art. Another is Teesside, an English chemical and steel hub where the industrial landscape was being soaked up and stored in the imagination of a young boy called Ridley Scott. And another leads to the Ozarks of Southern Missouri, where Dan O’Bannon relegates himself to the back of a school bus with the tomes of HP Lovecraft on his knee and stacks of Weird Fantasy by his side. There are many people whose contribution to Alien is indispensable, but for now these three are the most central, recognisable and pertinent.

As for Alien’s beginnings, they lie rooted, undoubtedly, in Dan O’Bannon — removing the film’s director or conceptual artists would have made for a very different movie, but without O’Bannon’s involvement there would have been no grand collaborative effort between this trio, no mind for the Alien to germinate and spring from, and no film at all.

Dan…

Daniel Thomas O’Bannon was born September 30th, 1946, in Shannon County, Missouri, to parents Thomas Sidney O’Bannon and Bertha Lowenthal O’Bannon. “I grew up in a small town in Missouri named Winona,” Dan told The Washington Post in 1979. “A dreadful place. We moved to St. Louis during my adolescence. That was even worse. If I had my finger on the button, the first place I’d blow up would be St. Louis. The whole medium of social interaction in St. Louis is games of humiliation. The ambience is depression, despair. For me the world is shaped like a funnel and St. Louis is at the bottom. It’s a fight to keep out of it.”

“My father was a carpenter with an IQ in the genius range,” he continued. “He was multi-talented in the arts, but he’d grown up too poor to be able to express himself. He always put people ahead of principles, but my mother was the reverse. She was physically violent. She’d throw me to the wolves for a principle.” Thomas O’Bannon kept a running journal (a habit that Dan would also pick up) that documented the formative years of his son’s life. Within its pages he recounts his son’s birth (Thomas checked his wife into hospital and passed the time seeing a Marx Bros. movie) as well as his flowering imagination:

“This morning we were discussing the green cheese and the man in the moon and kindred subjects. During the discussion the boy came up with the startling information that the man in the moon so loves green cheese (of which the moon is composed) that he eats up the whole moon every twenty-eight days or so and has to order a new one. So far as I know this little notion is original with him. He says he never heard it anywhere. Not bad, huh?”

~ Thomas O’Bannon, ‘The Book of Daniel’, excerpt from Jason Zinoman’s Shock Value.

Danny, as he was known at school, grew up without a television and with Hollywood itself seemingly “as remote as the moon”; the O’Bannons therefore entertained themselves by visiting the local cinema several times a week. “There was one theatre, and a drive-in outside of town,” Dan explained. “Movies were probably the single most important influence of my childhood; I loved them and wanted to make them, but I had no idea how one would go about getting to be a filmmaker.”

Meanwhile, he busied his childhood with filmmaking games (his friends serving as stuntmen and actors) and scanning the night skies for UFOs. His father encouraged his wonder for the inexplicable, running a tourist trap outside Winona known locally as Odd Acres that sold magic tricks and promised alien sightings and other celestial phenomena. Dan’s widow Diane O’Bannon told bloodsprayer.com that, “Odd Acres also included things like a stream of water that flowed uphill and an off-kilter room where you could have a picture of yourself taken standing at a gravity-defying angle.” One sign on the Odd Acres property read: ‘Impossible Hill! That strange place! You are tall. You are short. You can’t trust your eyes. And gravity goes crazy!’

In addition to running shop, Dan’s father also encouraged extracurricular mischievousness. “He also helped his father fake UFO landing sites on their acreage and watched as his father took UFO believers and the press around and told them about the landing he had witnessed!” (apparently, a Tom O’Bannon is listed as the witness of a 1957 UFO sighting in Winona, MO — the UFO was revealed to be a chicken brooder. The photograph can be seen in the publication Man-made UFOs 1944-1994.) In other photographs displayed at the Shannon County genealogical website a young Dan can be seen grinning as he seemingly suspends from a ‘gravity-defying angle’ and Bertha O’Bannon’s legs magically depart her torso.

Even from a young age Dan was discerning what did and didn’t work for him concerning the horror and sci-fi films that revolved through the local drive-in and theatre. One thing that turned him off was incessant gore and scenes of pointless torture. “There was a lousy, crummy little film called Horrors Of The Black Museum,” he said in 2007, “whose high point was a pair of binoculars that shoved needles into someone’s eyes. I saw that as a kid and I just found it sort of disturbing in the wrong way, just disgusting and unpleasant. You can divide horror movies into two general categories: sadistic or masochistic. In the sadistic films they invite you to enjoy the mutilation and to empathise with the monster. In the masochistic film you are invited to empathise with the victim, and to not like mutilation. Well, I make masochistic horror films.”

In addition to critique, he was soaking up whatever he could from the great filmmakers of the 40’s and 50’s. “[Filmmakers] these days [have] the monster doing terrifying things, but there ends up being too much of it,” he explained. “The terror still comes from the ‘in between.’ [Howard] Hawks obviously understood the whole idea of the ‘Terror in Between’, because the creepiest moments of [The Thing From Another World] arose from the interaction of characters between appearances of the monster. You weren’t sure of what the people trapped in that camp would do to each other when faced by the threat from outside.”

Other influences were literary. Specifically, pulp literature and comics. At twelve, Dan came across an anthology of horror tales (“Science Fiction Omnibus, edited by Groff Conklin,” he recalled) that included HP Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space, and a lifelong obsession with Lovecraft’s unique brand of cosmic horror took root. “I stayed up all night reading the thing, and it just knocked my socks off,” he later enthused. “One of the elements in the story is of course, vegetation growing out of season, and when I read it , it was mid-winter and we were living down in the Ozarks. Next day when I got out, the whole ground was covered in snow, and when I went out to look around, I found a single rose growing up through the snow, and it really spooked me, ‘Oh my god.'”

His adoration for Lovecraft would find its ultimate expression in Alien which, as he expressed in his essay ‘Something Perfectly Disgusting’, “Went to where the Old Ones lived, to their very world of origin. That baneful little storm-lashed planetoid halfway across the galaxy was a fragment of the Old Ones’ home world, and the Alien a blood relative of Yog-Sothoth”; but, for now, he contented to dream about being a filmmaker, an actor, or an artist. He would later comment that exerting his creative energies by writing helped him process feelings of anger about his surroundings: his mother was allegedly harsh, and school became unbearable when the affable, playful Dan felt the spotlight suddenly turn against him in a dreadful epiphanic moment.

“I could always make people laugh, in high school,” he told The Washington Post. “Then I began to discover that people were laughing at me rather than with me. I got angry. That anger has accelerated. I used to make a lot of jokes, I could stand up on a stage and make people laugh. But I mistook the laughing for people liking me, and I began to get angry … All through my childhood and my teens I was constantly picked on, attacked, assaulted.”

Despite these struggles, O’Bannon was averse to retorting with violence: when a classmate smeared shaving foam in his eyes he gave chase, held him against a locker, but was unable to bring himself to physically strike the bully; years later, an angry girlfriend would point a gun at him (“a .22 Colt varmint pistol”) but all he could do was disarm her and then beat himself with his fists. “I abhor violence,” he explained in ’79. “I don’t think I could portray it if I didn’t abhor it so much.”

The great turning point was 10th grade, I’ll never forget it. I was sitting at a play rehearsal, and I asked an upperclassman why I didn’t have more friends. He said, “If people don’t like me, fuck ’em.” That’s when it began. I went home to think about that. Fuck ’em.”

~ Dan O’Bannon, The Washington Post, 1979.

As a young man Dan enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis, the school of fine arts, where he studied with the intention “to be the next Norman Rockwell”, an artist famed for his depictions of American domestic scenes: cozy grandmothers, slumbering mutts, apple-cheeked Boy Scouts and the like. “I soon learned that the world only needed one Norman Rockwell,” he realised, “so I decided to try for the movies.” He enrolled at the University of South California film department, typically acronymised as USC, in 1968.

… Dark Star…

USC at the time was a hotbed of ambitious young would-be filmmakers including, among others, John Milius, Robert Zemeckis, and George Lucas, “who was a year ahead of me and therefore not of my tribe.” Francis Ford Coppola had graduated before O’Bannon’s enrolment, and Steven Spielberg had been rejected admission for poor grades, but graduates tended to hang around after completing their studies (usually to capitalise on the filming equipment and eager volunteers) and they brought similarly talented friends into USC’s orbit, which all coalesced to create an energetic environment that was spilling out as one contributory arm of what would be called ‘New Hollywood’ — it was a revolutionary movement in American cinema, and O’Bannon was in the thick of it.

“[W]hen I was studying there the auteur theory was the big thing – the director has to do it all. And I believed them, and in fact I taught myself how to do every job on a movie.” His first student films included 1968’s ‘Good Morning Dan’ (“Set in the then distant future of 2006, an old man reminisces on his days at USC”) and 1969’s ‘Bloodbath’ (“A slovenly young man commits suicide out of curiosity and boredom”); the latter film was shown in a class that included student John Carpenter, who decided to seek out and befriend O’Bannon — the two had already worked together on ‘Good Morning Dan’, on which Carpenter operated the camera, but it was O’Bannon’s later project that compelled Carpenter to strike up a creative relationship.

Carpenter, like Dan, had been exposed to science fiction and horror films as a kid, visiting the cinema to check out the latest in the big wave of monster movies that were besieging the screens throughout the 1950’s. Later, his enrolment at USC would further expand his interest and awe. “We had directors like Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks and John Ford come down and lecture us,” Carpenter told Deadline in 2014. “It was unbelievable! Roman Polanski was there with his bride, Sharon Tate, in 1968, with Fearless Vampire Killers. To sit and listen to Orson Welles … man, oh, man.”

Dan also found the frequent celebrity drop-ins to USC useful, passing his first script, a Western titled ‘The Devil in Mexico’ (which centred around “the disappearance of Ambrose Bierce into Mexico during the Revolution of 1917”) into Welles’ possession. “I had in mind it would be directed by David Lean,” Dan reminisced. “Orson Welles did see it, liked it, and passed it around, but nothing came of it.”

William Froug, a TV writer and producer whose credits included The Twilight Zone and Gilligan’s Island, also met O’Bannon on campus when the young student was passing out copies of his script. “One morning after my USC class was over, one of my students approached me,” he wrote. “Thin, emaciated, skin too pale, he looked like death lurking. He said his name was Dan O’Bannon. His cheeks were sunken, color pallid, his eyes dull. He handed me a screenplay and asked if I would read it.”

The screenplay was, again, ‘The Devil in Mexico’. Froug suggested changes and O’Bannon agreed. Froug spent some time reworking and trying to sell the script, but, according to his autobiography, it was quickly picked up by Peter Ustinov, who claimed it as his own, and the film was never made. Still, O’Bannon remained friendly with his former tutor and managed to pay direct homage to him in Dark Star, when his character Sgt. Pinback draws up to the camera and says, “I should tell you my name is not really Sgt. Pinback, my name is Bill Froug.”

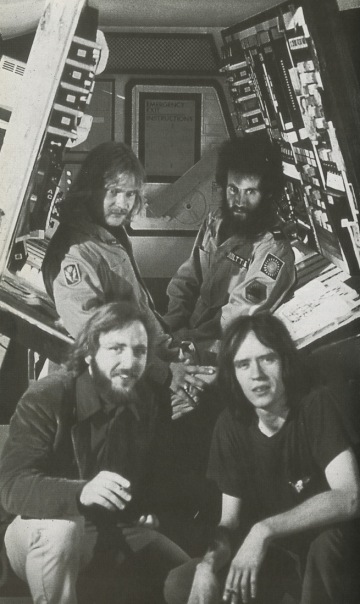

In August 1970 Dan met John Carpenter for dinner at the International House of Pancakes on Jefferson Boulevard, just across from USC’s cinema complex. “John told me that he wanted me to act in his graduate 580 project,” Dan explained. “It was to be a science fiction film called ‘The Electric Dutchman’, about four seedy astronauts in a small spaceship who are bombing a sun that is about to go supernova … It was to be twenty minutes long, in black-and-white.” Dan, whose interest in science-fiction had lapsed during his time at Washington University (“I let that kind of fall by the wayside. I was interested in experiencing a ‘real life’”) now jumped at the opportunity: “I said, not only did I want to act in it, I wanted to help him with a lot of other things, like the script and special effects. He accepted, and we embarked.” He now had a project, a collaborator, and a forte. After all, he knew the science-fiction genre “Like the back of my hand.”

In addition to finding a use for his repository of science-fiction know-how, Dan was also happy to get in front of the camera as a performer. “I’d always acted from childhood on,” he told Den of Geek in 2007, “and I was always in theatrical productions at school and then college. It was an obvious thing to do in Dark Star. Since we weren’t paying anybody, the other actors were unreliable in terms of showing up. And I was there and so I acted in the thing.” Dan had also performed in several student films, playing a proto-Michael Myers in Terence Winkless (who later penned The Howling) and Alec Lorimore’s 1971’s Judson’s Release (“A young man returns to a small town and begins to torment a girl who is babysitting a little boy”), a small feature that apparently presaged Halloween. Decades later Carpenter, when told that Dan had once joked about giving up writing to pursue the easier task of acting, replied with earnest that, “O’Bannon’s actually a very good actor. He should pursue it, he could be really good.”

Trouble arose when Dan’s parents decided to cut him off financially and told him to return to Missouri. To keep him in L.A. Carpenter invited the penniless Dan to move into his apartment, and it was there that they bashed ‘The Electric Dutchman’ into shape. Dan had a few ideas to contribute: a cryogenically frozen Captain was one, as was the star-struck Talby’s obsession with the mythical Phoenix Asteroids and the sentient and argumentative bomb from the film’s closing moments. “The way we wrote together was: We would go off separately and write the scenes we liked best, and then John would assemble all the material into its final form.” For his part, Carpenter found his new partner’s input indispensable. “Dan contributed mightily to the tone of the film; many of the funniest moments are his ideas.” They also settled on a new title for their movie: ‘Planetfall’.

The two began searching for a crew to help bring their film together. “I composed the score for my first film Dark Star because I was cheap and fast,” Carpenter told thequietus.com in 2012. “I talked to a couple of other composers but they all seemed weird. One guy had glitter all over him. Not that wearing glitter is a bad thing… it just didn’t inspire confidence.”

Though O’Bannon was a confident DIY effects man, he sought greater artistic talents to design the spaceship needed for their movie. For this, he sought cartoonist Ron Cobb, whose bitingly satirical strips for the Los Angeles Free Press had found cult appeal, having been reproduced in counterculture magazines and papers like the Underground Press Syndicate, and who had recently turned to drawing up frightening lizardmen and two-headed golems for magazines like Famous Monsters of Filmland.

“I tried to reach Cobb to get him to design the whole film, but he was unreachable,” said O’Bannon. “For weeks his phone rang without an answer, and then it was disconnected, and then I got his new unlisted number but it was invariably answered by one of the girls who were living with him, who always told me he was out. It was impossible. It took another year and a half to track him down and get him to agree to design us a nice, simple little spaceship for our simple little movie. Finally, one night about ten pm, Carpenter and I drove over to Westwood and roused him out of a sound sleep. He was hung over from an LSD trip and I felt kind of guilty, but I had to have those designs. We took him over to an all-night coffee shop and fed him and got him half-way awake, and then he brought out this pad of yellow graph paper on which he had sketched a 3-view plan of our spaceship. It was wonderful! A little surfboard-shaped starcruiser with a flat bottom for atmospheric landings. Very technological looking. Very high class stuff.”

Casting the film with friends and building the sets themselves, Dark Star was completed as a short but expanded into a feature length film. “We were approached by a friend of ours named Jonathan Kaplan, who subsequently produced most of John Carpenter’s movies,” O’Bannon explained. “He was also in film school then and had a somewhat wealthy family, and he said that he would put in some additional money if we would expand it to feature length.” New scenes included some mania with an alien (in reality, a beachball) in addition to other ancillary material that padded out the length. Unfortunately, the extra expense and effort seemed for naught: when the film was released Carpenter and O’Bannon drove to a theatre and asked the manager if they could observe the audience. The manager replied: “What audience? There’s eight people in there.”

Of his Dark Star days, Carpenter told esquire.com in 2014 that “I was a punk. I didn’t know anything. I thought I did, but I didn’t. That was a baptism of fire, of sorts […] Back in those days I didn’t know anything. We thought we were hot shit, but we weren’t. We were sadly mistaken. I remember getting my first bad review on that film. I’ve had many since, but that was the first one. It was so shocking. That shows how naive I was then […] They said something like, ‘It betrays its dingy origin.’ I remember that line. I thought, Really? Jeez, man.”

In 2014 Carpenter told Deadline.com that, “After my first film, Dark Star, I expected the movie industry as a whole to greet me as a savior, pick me up in a limo and take me to a soundstage and anoint me as a director. That didn’t happen. I got an agent out of the first screening of Dark Star, and he said to me, ‘What you need to do is write your way into this business.’ So I started churning out ideas and writing screenplays.” But amid the ego-busting was a silver lining: “Dan O’Bannon and I were almost blinded at the time,” Carpenter told rollingstone.de. “We thought everything was quite simple, and we made a great feature film. Thank God, because if we had not indulged in this illusion, then we would have also failed in the film business.”

That audiences -whenever they actually gathered- did not laugh at the film’s jokes perturbed O’Bannon, who, in his despondency and dissatisfaction with how Dark Star turned out, decided to take the same premise -a beleaguered and bickering space crew, the meniality of interstellar life, an alien intruder, etc- and infuse it with scares rather than laughs. He had already started preliminary note-taking for Alien in 1972, apparently anticipating at the time that Dark Star would not satisfy him. Other creators would look on Dark Star as a sort of unmined resource. Red Dwarf co-creator Doug Naylor commented that it was a viewing of O’Bannon’s film that spurred the idea of a dingy space comedy. “We’d seen Dark Star,” Naylor told Starburst magazine, “I remember remarking to Rob [Grant, co-creator] at the time that I couldn’t believe no-one had done a sitcom like that because it seemed like such a good thing to do. So it was the old memory of Dark Star.”

While Dan was at least encouraged by Dark Star enough to revisit and remold it into Alien, Carpenter, for his part, was so disappointed that he abandoned its premise altogether. “I don’t think I ever want to get near that idea again” he told CraveOnline.co.uk in 2013. “Oh brother, once was enough.”

…and Dune

Dark Star’s greatest legacy wasn’t its lacklustre release and reception, or even its modern popularity (it remains firmly cult) but how it engendered Dan’s fruitful artistic collaborations with Ron Shusett, with whom he would write both Alien and Total Recall. Shusett told midniteticket.com that, “When I saw [Dark Star] I said, ‘Wow, I should be working with this guy’. I hadn’t made any movies and I had been struggling for four or five years at that point.” Shusett tracked O’Bannon down, finding him living in an attic at USC, and the two agreed to work, firstly on Dan’s own project, Star Beast, later titled Alien, before tackling Total Recall, which Shusett had optioned and brought to the table.

The process of scripting the film has been covered extensively in Writing Alien, but in brief before it was finished Dan was contacted by Chilean avant-garde director Alejandro Jodorowsky, who had seen Dark Star and, impressed by O’Bannon’s ability to multi-task and concoct low-fi visuals, decided to hire him to take charge of the special effects on his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s opus, Dune. O’Bannon accepted, and set off for Paris.

O’Bannon’s time in Paris introduced him not only to Swiss artist HR Giger but also to English artist Chris Foss and French comic artist Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, all of whom would later work on Alien. In HR Giger Dan found an utterly unique artistic sensibility that, he reckoned, if brought to the cinema could be transformative. And in Moebius he found another collaborator with whom he would, with no inkling at the time, influence science-fiction for decades to come.

“After a while [Moebius] got tired of me looking over his shoulder,” explained Dan, who had been impressed by the talents Jodorowsky had managed to summon for the film, “so he asked me to go and write him a comic-book story, a graphic story that he could publish in his magazine, Metal Hurlant.” The strip that he concocted he called The Long Tomorrow. “It was of course a film noir in the future. I didn’t think about it for many months until an American publisher decided to publish Metal Hurlant in an English-language edition, and call it Heavy Metal.”

“Dan came to Paris. Bearded, dressed in a wild style, the typical Californian post-hippie. His real work would begin at the time of shooting, on the models, on the hardware props. As we were still in the stage of preparations and concepts, there was almost nothing to do and he was bored stiff. To kill time, he drew. Dan is best known as a script writer, but is an excellent cartoonist. If he had wished, he could have been a professional graphic artist. One day, he showed me what he was drawing. It was the story board of The Long Tomorrow. A classic police story, but situated in the future. I was enthusiastic.”

~ Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, The Long Tomorrow introduction.

Dan had originally drawn The Long Tomorrow himself, but Moebius, impressed, asked for free rein to redesign the strip. “I scrupulously followed Dan’s story,” said Moebius, though he admired Dan’s artwork enough that he claimed, “One day I wish we could publish our two versions side by side. As the strip has pleased everyone, I asked Dan about a sequel, but it did not get his attention, so was simply an adventure I never designed.”

Their work, initiated as a distraction, would become the visual inspiration for later landmark science-fiction movies and comics, including Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira and William Gibson’s Neuromancer, and some have pointed to what looks like the imperial probe droid from The Empire Strikes Back tucked away within The Long Tomorrow as well. The most obvious and touted influence is 1982’s Blade Runner. Indeed, Ridley told Film Comment journalist Harlan Kennedy in 1982, “My concept of Blade Runner linked up to a comic strip I’d seen [Moebius] do a long time ago. It was called The Long Tomorrow, and I think Dan O’Bannon wrote it.” Ridley again mined The Long Tomorrow for imagery in 2012’s Prometheus and an alien from the comic known as an Arcturian may have informed a gag in Aliens.

“It’s entirely fair to say,” stated Gibson, “and I’ve said it before, that the way Neuromancer-the-novel ‘looks’ was influenced in large part by some of the artwork I saw in Heavy Metal. I assume that this must also be true of John Carpenter’s Escape from New York, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, and all other artefacts of the style sometimes dubbed ‘cyberpunk’.” Dan commented on The Long Tomorrow‘s influence in a 2007 documentary on Jean Giraud. “Ridley kind of did an unauthorised borrowing of that city for Blade Runner, and he’s right – it does make a good image!” Moebius himself was asked to contribute to the film, but couldn’t, stating that he is “very happy, touched even, that my collaboration with Dan became one of the visual references of the film.”

Jodorowsky’s Dune fell apart before production could begin, with Jodorowsky blaming American theatre managers who balked at the thought of a European film sharing as many screens as an American one, and Chris Foss elaborating that the French production company pulled funding after it became apparent that American co-financers were not likely to be found after failed attempts by Jodorowsky to procure them. The budget was already extraordinary, the imaginations of the filmmakers seemed beyond reining in, and Camera One lost the nerve to bankroll the project. Dune would later find its way to the screens in 1984 under the auspices of David Lynch; though he succeeded in making the movie, Lynch would write it off as a failure, as did audiences and critics. But the Dune days, though they seemed like yet another stumbling block, would turn out, as Dark Star did, to be a stepping stone for greater opportunities.

Upon returning to the United States O’Bannon found himself broke and living on Ron Shusett’s couch, but a phonecall from Gary Kurtz, who was producing Star Wars, gave him enough money to rent his own apartment. Kurtz had been impressed by O’Bannon’s whizz-kiddery on Dark Star (which included what is cited to be the first ‘hyperspace’ effect as the stars rush past a spaceship entering lightspeed) and had wanted him to come aboard Star Wars earlier, but Dan had already committed himself to Dune. “Kurtz called me again and said, ‘Well, Star Wars is just about finished, but we still need some people to do special effects work, to do clean-up. Are you interested?’ Since that time I was absolutely flat-broke, I was very interested. So I went to work on Star Wars for a few months doing computer graphics.”

Eventually, Dan and Shusett managed to finish the Alien screenplay and brought it to Roger Corman, who offered to finance the project. “Everybody would think a goddamn lizard coming out of somebody’s chest is nuts,” said Shusett. “Corman said, ‘Yes, I’ll give you $750,000 to do it right now.’ Right before we signed the contract we accidentally got the movie from Fox, which was the first studio we showed it to. Corman was fine, he said, ‘God bless you! If you can do it on a big budget. It will be someone else I’ve discovered. Dan and Ron. I don’t resent you.’ It did turn out to have a huge impact on cinema and we were ready to do it for $750,000.”

Alien had been brought to the attention of Twentieth Century Fox by Brandywine producers Walter Hill and David Giler. The duo rewrote the original script, changing the names and removing the alien elements, all in an effort to craft a visceral, stripped down space thriller. The pyramids, alien hieroglyphs and civilisations were, Hill thought, too hokey, too von Däniken. They excised these elements and their redraft saw Fox greenlight the film. O’Bannon was hired as a ‘visual design consultant’ for the film, a position that Giler mocked but which paid dividends for the production: O’Bannon was able to insist that Ron Cobb, Chris Foss, and HR Giger be hired to design the film’s environments, characters and creatures. Moebius would later briefly join at director Ridley Scott’s behest.

The studio happily accepted Cobb and Foss, but balked at Giger’s artwork. O’Bannon had already taken the initiative to pay Giger for some conceptual designs, but the Swiss artist would not be formally hired -or it seems, accepted- by the studio until Ridley Scott came aboard and Dan rushed to show him Giger’s work.

“He’s great,” Scott said of O’Bannon in Fantastic Films. “A really sweet guy. And, I was soon to realise, a real science-fiction freak … He brought in a book by the Swiss artist HR Giger. It’s called Necronomicon … I thought, ‘If we can build that, that’s it.’ I was stunned, really. I flipped. Literally flipped. And O’Bannon lit up like a lightbulb, shining like a quartz iodine. I realised I was dealing with a real SF freak, which I’d never come across before. I thought, ‘My god, I have an egg-head here for this field.’”

Not only did O’Bannon introduce Ridley to the artwork of HR Giger, but he also, according to Cobb, rewrote much of the script on the set. The initial pre-production rewrites by Walter Hill and David Giler removed many of the elements from Dan’s script that wound up in the film, such as the Space Jockey (a human pilot in their version), the alien pyramid and egg silo (government installations in their version; combined wth the derelict craft in the film) and the Alien was retooled as an experimental biological weapon. Other purported rewrites were bizarre, pitting the Alien against a variety of historical figures.

“I think that the real problems were in Dan’s sphere,” said Cobb, “because of what [Giler and Hill] did with the rewriting. It’s terrible, sloppy revisions, some of them pointless. It was very difficult for Dan to tighten the thing back up to keep it consistent and have it make sense.” Both Shusett and O’Bannon were alarmed at the content of the rewrites, but had little to no say on such issues, so, they took the original draft to Ridley himself. Of that attempt, Shusett said, “Ridley read [the original script] and went, ‘Oh yes. We have to go back to the first way. Definitely.’”

Once the film was in production at Pinewood Studios O’Bannon revealed that David Giler “left for mysterious reasons”, apparently having left script rewrites unfinished and, since Walter Hill had stayed in the States, left the film with no on-set writer to untangle any problems with the script, which was in a state of fluctuation due to time and budget concerns. “And finally at the last minute,” said O’Bannon, “I saw that everyone, including Ridley, was so fed up with Giler and Hill’s failure to make any of the promised revisions that they said they were gonna make, that a little sliver of opportunity was created. I was standing there, I said, ‘You know, I’ll fix it if you’ll let me.’ [So] there were two weeks of frantic mutual work between all of us, trying to put the script into a shape that they liked. By the time we got done, it was maybe 80% of the what the original draft was. What we got on the screen was actually very close to the original draft.”

Cobb told Starburst magazine at the time that, “The whole film is in a constant state of flux. Script revisions are going on every day. Things that haven’t been shot are still being rewritten and that’s why Dan is feeling better, because he and Ron Shusett are having substantial input into these last minute script changes. They’re fixing it quite well, strengthening it considerably.”

Years later Cobb would add that, “The final film is not the film that Dan and I would have made, or Dan, Giger, and I or Ron Shusett. It’s not exactly that film, but it is close enough to Dan and Ron’s. They stayed there and fought for it inch by inch, day by day to keep it from going too far from the original concept.”

A 1979 Washington Post interview found O’Bannon pained but gleeful that Alien had shocked audiences so thoroughly — “O’Bannon meant the movie as an ‘attack’ on the audience,” it read. “He wanted to ‘get even,’ he says, for the way they scorned him for his first movie, Dark Star. He wanted to ‘beat the stuffing’ out of us, he says. He means it.”

The aftermath of Alien’s release saw Dan cut a solitary, frustrated figure in the media. His propensity to say what he thought, belligerently if need be, alienated him from many in Hollywood. “I’m used to being alone now,” he told The Washington Post. He also added that despite managing to turn one failure around into a bona fide success by coming at it from a different angle, Dark Star was still “a trauma from which I have yet to recover.”

More concerning was his health: journalists and filmmaking friends occasionally detailed Dan’s struggle with what was eventually revealed to be Crohn’s Disease, for which he underwent extensive surgeries and periods of convalescence. For many years he suffered with no diagnosis or alleviating treatment. “O’Bannon explained that he suffered from a rare disease that produces severe abdominal inflammation and accompanying pain,” noted his former tutor, William Froug. “Doctors had told him it was inflammatory bowel syndrome, and it was genetic … For O’Bannon, poverty and pain were nuisances he would endure as the price of success. ‘Every dime I can scrape together goes to pay doctors,’ he told me with some bitterness.”Jason Zinoman writes in Shock Value that Dan’s doctors convinced him his bouts of agony were due to appendicitis, but a subsequent surgery didn’t stop the pain. “It wasn’t diagnosed correctly until 1980,” Zinoman writes, “but for years the incurable condition disrupted the normal process of digestion, inflaming his bowels, shortening his gut, cutting off the transit of food through his belly.”

Chris Foss likewise related to Den of Geek that Dan had suffered a particularly agonising incident after eating junk food, but he also added that O’Bannon , as he had with his everyday frustrations, managed to derive some creative output from his painful experiences. “Long before he came to Paris,” Foss said, “he ate some fast food and woke up in the night in incredible pain and actually had to be taken to hospital; and he imagined that there was a ‘beast’ inside him. And that was exactly where [the chestburster] came from.” HR Giger corroborated this in an 1999 interview, saying, “Dan O’Bannon, when he was writing the script, had a stomach pain and he wanted the pain to go away and came up with the idea of the pain leaving through the stomach, so he invented that.” According to The New York Times, O’Bannon also told them: “The idea for the monster in Alien originally came from a stomach-ache I had.” Much of his initial wage from Twentieth Century Fox was used up paying off his medical expenses. “I’d been under much stress and other problems plus not taking care of myself,” he said, “that I came down with a very bad stomach ailment in 1977. I was sick a great deal of that year, I was in and out of the hospital.”

Alien’s production had provided a brief respite; O’Bannon suffered little ill-health during his time in England, having been invigorated by the process of making a film that he himself had imagined. “I was stricken with a debilitating stomach disease still undiagnosed and spent most of ’77 in hospital making decisions by phone,” he told Media Scene in ’79. “So I was feeling really miserable and in intense pain when Gordon Carroll called up and says, ‘We’re all going to London to make Alien. Let’s go!’ I groaned and bitched, but everybody persuaded me I’d better do it. I’d already spent thousands of dollars from my Alien option and preliminary money on medical bills, and it looked like I’d need more, so I went to England.”

“Lo and behold,” he continues, “in the process of working, I made what appears to be a complete recovery. It was the first time I’d felt normal in better than a year.” In the time between the film’s completion and release O’Bannon revealed that loneliness, dissatisfaction, and possibly the pain of his stomach ailment sent him somewhat off the track. “Sometimes, I like to get totally stoned out of my mind,” he said. “Liquor, marijuana, everything. Just get completely stoned, and go to some sleazy strip joint and spend all night watching the girls dance.”

“So he’s rich. Famous. Vindicated. If it weren’t for his stomach attacks, he might get his first shot at happiness; but they started coming on during the last year of work in the movie, incredible gut pain and nausea that the doctors, after endless scans and probes, found no cause for, whatsoever. The only cure is to shoot him full of Demerol and feed him intravenously. He just got out of the hospital a few weeks ago after one bout, but his worst attack came during the sneak-previews – one of the preview cities being his hometown of St. Louis, ironically enough.”

~ Henry Allen, The Washington Post, July 29th 1979.

During his interview journalist Henry Allen noticed that O’Bannon sat with his trousers unzipped; this was to ease the pain he felt from doubling over or sitting in a prone position. When Froug interviewed Dan for his 1991 book The New Screenwriter Looks at The New Screenwriter, he noted that he was “hooked up to a morphine drip while agitatedly pacing his UCLA hospital room.” But despite the agony, O’Bannon kept busy, all the whole plotting his next script. “O’Bannon continued to write,” said Froug. “Writers write because they can’t not write, they don’t waste time thinking about what sold or what didn’t. Regardless of the outcome, they put the seat of their pants back down on the seat of the chair and keep writing.”

His struggles with Crohn’s made travel difficult; stress only exacerbated his condition, and assuming the mantle of director in such straits would have been to invite tremendous physical agony and humiliation. In the 1980’s British journalist Neil Norman interviewed him and related that “Dan O”Bannon is a sick man. Shortly after my visit he had a date with a surgeon who was going to remove a large section of his bowels. Drawn and grey with pain, he was describing in minute detail the plot of his next film to someone on the other end of his radio telephone.”

But the 1980’s also saw Dan find equilibrium in his personal life, marrying his wife Diane in 1986 after first meeting at USC back in 1971. “Dan was too wild for me in the early days,” Diane said of their early years, “and he was completely focused on his career. By the time he had directed Return of the Living Dead he’d calmed down a bit so when he asked me to marry him I said yes.” His resolve to work, to exert and express himself creatively, never waned. “I’m not tough,” he told The Face in 1986. “God did not mean for me to be a physical man of iron. He meant for me to be a mind. Anything I do in life is a compromise because whatever I do that I like, there will be something about me that makes it difficult. My health problems do not affect my ability to work. No matter how much pain I’m in it never stops me writing and it never affects the quality of my work. Part of this is because writing is a narcotic. When I don’t feel well, it is a way to escape from the pain.”

“I may write another script, to direct myself,” he had told Fantastic Films in ’79, “but I’m never going to get into hassle I got into Alien.” Despite this disavowal, and despite his misgivings about sequels, O’Bannon would further cement his cult success when he directed 1985’s ‘off-shoot sequel’ The Return of the Living Dead; the producers, for legal reasons, encouraged him to make it as different from George Romero’s original Dead films as he could. O’Bannon gave the film a comedic tone that distanced it from the doomy atmosphere of the original Dead films and introduced zombies that hungered for brains and ran after their victims instead of shambling, decades before Danny Boyle and Zack Snyder featured similarly athletic zombies in 28 Days Later (2002) and Dawn of the Dead (2004) respectively. “I was watching TV and there’s some young director who has done a zombie movie very recently,” Dan told Den of Geek in 2007, “he was congratulating himself on inventing the idea of swiftly-moving zombies. And I thought, ‘Hmmm, I guess he’s never seen Return Of The Living Dead.’ Apparently we both invented it.”

The long-gestating Total Recall, released in 1990, some fourteen years after its writers first met (Ron Cobb was also involved) would not be the last film that Dan contributed to, but it certainly topped off his achievements with aplomb; the film was critically and commercially successful, is considered one of Paul Verhoeven and Arnold Schwarznegger’s best films, and is, perhaps appropriately, thought of as one of the last of its kind –a science-fiction action spectacle with brain, brawn, and the last to use many ‘extinct’ practical effects and one of the first to utilise many digital effects that are common today.

Dan O’Bannon’s fascination with the macabre may be said to have originated in his discovery of Lovecraft -his sense of wonder and love of science fiction seem to have already been there, instilled in him by his father- and the story which ignited his fascination, The Colour Out of Space, certainly stuck with him. HR Giger told Cinefantastique in 1988 that Dan kept “telling me he would like to do Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space with me as soon as he’s able to raise the necessary funds. That could be interesting because he’s definitely one of the greatest Lovecraft experts around.”

Unfortunately, the passion project never materialised. John Carpenter likewise had trouble selling the idea. “I tried to pitch an NBC mini-series, The Colour Out of Space, and they didn’t really care,” he told denofgeek.com in 2008. “They’d read it and say, ‘What is this shit?’ They don’t get it. They don’t dig it.” Despite Lovecraft’s immense influence on filmmakers, Carpenter opined to CraveOnline.co.uk in 2013 that “There really hasn’t been a good Lovecraft movie. Well, mine [Mouth of Madness], but that wasn’t really picked up.” In summer 2009 Dan recieved the Howie Award, presented “for his lifelong promotion of the work and themes of writer HP Lovecraft.”

Dan O’Bannon passed away December 17th, 2009, after a prolonged struggle with Crohn’s Disease. For much of his life his forthrightness and unapologetic honesty rubbed many the wrong way and reduced many bridges to smoke and rubble, and though he was not a familiar name like Spielberg or Lucas, his death prompted odes from science-fiction and horror fans and outlets who testified to his work and efforts on Dark Star, the aborted Dune, Star Wars, Alien, The Return of the Living Dead, and Total Recall. “Jason Zinoman,” says Diane O’Bannon, “who interviewed Dan for Jason’s upcoming book ‘The Monster Problem,’ told me after he died that Dan had said to him ‘my wife understands me.’ I think that is the greatest compliment a wife can hear.”

“I would say Dan O’Bannon is probably one of the most important and most overlooked individuals, especially in horror, but in movies in general,” says Dino Everett, the archivist at USC who uncovered many of O’Bannon’s student films. “From the research I did compiling this project I soon learned that O’Bannon was this unsung hero, not only of modern horror, but also for his time here at USC. His work here in the 1960’s was really quite advanced and ahead of its time compared to many of his classmates, and he seemed to not only be a jack of all trades, such as writer, director, actor, makeup and effects, but also seemed to be a one man creativity catalyst contributing often to his fellow classmates’ projects.

The other thing I learned through all of this was that he was a fiercely loyal individual and showed a caring side that many might not suspect. In the 1990’s an old classmate of Carpenter and O’Bannon’s named Charles Adair (who made the zombie film The Demon, included in this project) was in failing health and in need of funds for his medical bills. O’Bannon co-wrote a script with Adair for a horror project called Bleeders (1997) and gave Adair all of the profits made from the writing job to help with the bills.”

Matt Lohr, who helped shepherd Dan O’Bannon’s Guide to Screenplay Structure to print in 2012, said of his mentor, “I always thought it was ironic that Dan died the morning Avatar came out. Several months later, Avatar went on to become a Best Picture nominee at the Academy Awards. If there was no Dan O’Bannon, or people like Dan, then Avatar wouldn’t get nominated at the Academy Awards. Dan elevated a genre through his respect for it. He elevated it in the eyes of others so they could say, ‘Yes, this movie has spaceships, monsters, and aliens, and it’s one of the best pictures of the year.’ And Dan’s one of the reasons we have that.”

See also: Interview with Dan O’Bannon