“If I have a space ship worth god knows how much money and I’ve got to have a Company man onboard and that Company man is going to be a goddamn secret […] He is going to be a perfect looking robot. So that was the Ash thing […] I just wanted to have the same idea that the corporation would have a robot onboard every ship, so that when you are asleep in hyper-sleep for three or four years going at 250,000 knots an hour, you will have a guy wandering around like a housekeeper. He’s a housekeeper and he’s got full access to everything. He can look at all of the films. He can go into the library… he can do whatever he wants, and that’s David.”

~ Ridley Scott, collider, 2012.

Fondly remembered as one of Prometheus’ better parts, if not the best part, the android David inhabits a middle-ground between Ash and Bishop – he is malfeasant, but is not an antagonist; he valets the Prometheus crew, but is ultimately not beholden to them.

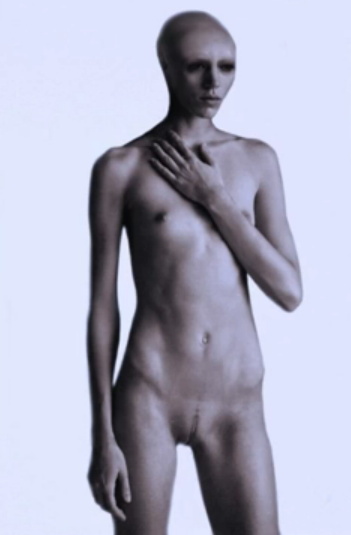

In Jon Spaihts’ Alien: Engineers David is first introduced aboard Weyland’s Wheel, where he acts as a concierge. “He’s cunningly built,” it reads, “but no one would mistake him for a real human being.” When Weyland is introduced, he elaborates a little more on his creation. “He’s a prototype,” he tells Watts. “Our 80 series. One of a kind for now, but if he performs, he will be legion.” This is obviously different in the film, where David appears very much human and, in the promotional materials at least, is said to be mass-produced already. Another divergence in the story is that Weyland does not board the Prometheus ship in secret, but instead sends David along as his “eyes and ears”.

There is also a very interesting exchange where David speaks with Watts and Holloway about his design specifications and capabilities:

David: My design’s not intended to convince. Simulating humanity is a complex task that diverts resources. My designers dispensed with that burden to optimize for intelligence.

Watts: Why look like a man at all? Why not be a box on wheels?

David: Being shaped like you, I can use spaces and equipment designed for you. But I’m not so limited. I hear frequencies you can’t hear. I see wavelengths of light invisible to you. I move faster. Exert greater force.The scientists look at David in wonder.

Watts: You see yourself as a superman.

David: No.He turns his unearthly eyes on them.

David (cont’d): Not a man at all.

David, overall, is very much an antagonist in Spaihts’ script. At first, he still serves the same function he does in the film: he decodes the alien hieroglyphs and quickly grasps the Engineer technology, and he still rescues Shaw after she is swept away in the storm, but by the midpoint he starts to display contempt for the human crew and, in one scene with Watts, he reveals a hidden agenda:

David: I was given two operating protocols for this mission. I was to render you every assistance – until you discovered what Vickers would call a “game-changing technology.” I was given a specific list. Then I was to go to protocol two […] Under protocol two I was to make sure that you and Holloway never spoke to anyone about this place. Various acceptable ways of making sure of that.

When he finally assaults Watts he does so with palpable malice, and when he gives chase he “runs like a demon, his legs steel pistons.” When he captures her it is in a grip akin to “iron manacles”. He then impregnates her with Alien spore. Interestingly, when the facehugger emerges, David strokes it gently – the facehugger ignores his touch and reaches for Watts.

“Subsequently, David, fascinated by these [Engineers], begins delaying the mission and going off the reservation on his own, essentially because he thinks he really belongs with the Engineers. They’re smart enough and sophisticated enough, great enough, to be his peers. He’s harboring a deep-seated contempt for his human makers.”

~ Jon Spaihts, Empire, 2012.

Watts expels the embryo in the Med-Pod, and she, Vickers and the rest of the crew attempt to stop David from re-activing the Juggernaut. He has gone rogue and has prohibited the Magellan ship from leaving the planet. The Juggernaut ship, David hopes, will resume its mission and annihilate mankind. It is revealed that he is fitted with behavioural inhibitors that will bend him to Vickers’ command, should she be able to reach him in time, but unfortunately, David harnesses the Engineer technology to override these countermeasures. “To interface with the Engineers’ computers,” he explains, “I had to learn to think in trinary code. Hardest thing I’ve ever done. And most unexpectedly…it delivered me from slavery. My behavioral limits were circumvented. I’m free.”

He awakens the last surviving Engineer and the encounter goes essentially the same way it does in Prometheus:

The Sleeper turns in astonishment. He looks down at David and answers in the same tongue. He is angry, accusing. He points at David, at the humans. Tones of accusation.

David cajoles, soothes, pleads. The Sleeper descends toward David. David spreads his arms in welcome – undeniable emotion on his face. Joy. The Sleeper lays his hands on David’s head as if blessing him. David is rapturous. The Sleeper speaks a single phrase

– – and tears David’s head off.

In the end, David’s decapitated head solicits Watts for rescue, claiming that he will need her. The script never tells us if she does set off with him, ending on a note similar to John Carpenter’s The Thing. “It was plain that David and Shaw were going to have to work together and deal with one another if they were to survive,” Spaihts told Empire. “That one shot of the ship taking off in the finished film really focuses you on a particular outcome, whereas my ending was much more open as to what was going to happen next. But it was very much about this shattered android and this scarred woman being left with no-one but each other to carry on with.”

Of course, the script underwent some drastic overhauls when Damon Lindelof was given rewriting duties on the project. In addition to removing the Aliens, eggs and facehuggers, he also remolded the role of Spaihts’ android. “I also became obsessed with David as the central character of the piece,” Lindelof told mtv.com in 2012, “and did everything I could to think of the movie through the robot’s point of view. Mostly because robots are awesome, but also because robots are awesome.”

He told The Hollywood Reporter that “I was really interested in and catalyzed by the robot, David — I felt like he was going to become the central figure of the movie. Because in the genealogical chain of things, there are these beings that may or may mot have created us, then there’s us, and then there’s the being that we created in our own image. So we’re on a mission to ask our creators why they made us, and he’s there amongst his creators, and he’s not impressed. Oddly enough, the one nonhuman human on this ship — that’s sort of a prison — exists to question why it is we’re doing this in the first place.”

“The idea that by creating a being in their image, humans can become gods. In the film, it is clearly stated that David, the android played by Michael Fassbender, ‘has no soul.’ I was interested in showing that as the film [progressed] the character is showing more and more feelings. Especially when one of the characters points out that he is not a ‘real boy’. David is upset, even angry, but he keeps his cool. In this, he is more human than the humans…”

~ Ridley Scott, leFigaro, 2012.

David’s role in Prometheus should be familiar to readers, but there is some interesting, if not contentious, background information to be gleaned from the promotional materials for the film regarding David and his android ilk. The Weyland Industries timeline, which again arguably has a tenuous connection to the actual series canon, details the creation and development of various David models beginning 2025 A.D.

The first David is ‘born’ on 7th January of that year (according to the Nostromo Crew Profiles, he shares a birthday with Ripley) and the timeline provides an interesting detail: “He is affectionately called David, a name Sir Peter Weyland had initially reserved for his own human son.” The next year Weyland patents “a chemical composition of classified properties able to almost perfectly replicate the biological features and textures of human skin.” From thereon, the development of David-type androids rolls on: David 2 is ushered into the world in 2028, and David 3 in 2035. The timeline notes: “After android regulations are lifted, the third generation David is deployed internally to test human acceptance of cybernetic individuals. Results are encouraging.” Further models appear in 2042, 2052, 2062, 2068, and model no. 8 follows sometime between 2073 and the opening of the movie.

Also for the promotion of the film, mock commercials were made to advertise the new David 8 line of android:

The Weyland Industries website offered all sorts of specifications and blurbs for the David 8 line. “David 8 is guaranteed to surprise you,” it promises. The model is “fluent in all known languages through a dialectic implant and can infer the linguistic components of entirely new languages if encountered. Communication between humans and David 8 should feel entirely fluid and natural.”

The site also proclaims that “His cadmium endoskeleton is guaranteed for the life of the product”, that he can blend “seamlessly into human environments” and instills a “strong sense of trust in 96% of users.”

Additional feature specs:

- Multi-degree range of motion greater than human capacity

- Micro-distributed accelerometers

- 30x visual magnification with increased depth of field

- Low-light auto-adapting feature (with assisted low-light focusing)

- Non-reactive Polyurethane coating

- 700-lb lifting capacity

- Polymer-encased brain stem component

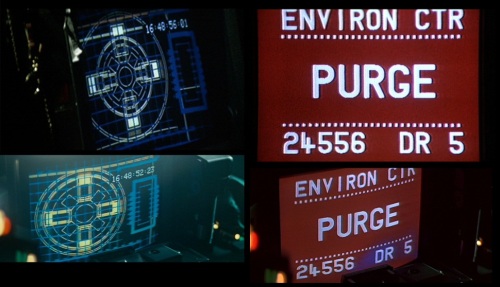

Then of course there is his maker’s signature, so prospective customers know he is the genuine, Weyland-approved product:

In terms of his physical appearance, Fassbender told Time that “the inspiration we used was David Bowie and The Man Who Fell to Earth, and for films there were the replicants in Blade Runner. Greg Louganis, in terms of physicality. Lawrence of Arabia of course, and Peter O’Toole as Lawrence, and Dirk Bogarde. They were the ingredients.”

“I watched Blade Runner and I looked at the replicants. Well, I looked at Sean Young. There was something in her character, a quality there that I kind of liked for David, this longing for something or some sort of a soul at play there, a sort of vacancy also, a sort of vacant element. I don’t know exactly what, I just knew there was a quality there that I liked.”

~ Michael Fassbender, collider, 2012.

When it came to dressing David they decked him in a grey Zhongshan suit, also worn by Vickers, and inspired by the spartan Communist uniform popularised by Sun Yat-sen and famously worn by Mao Zedong and also by pop culture dandies like Andy Warhol and David Bowie. David’s green fatigues also square him up with Bowie’s appearance in 1983’s internment camp drama Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.

David also exhibits peculiarities (for a supposed machine who only simulates human behaviours for their comfort) like vanity and obsession. One thing close to his heart, so to speak, is David Lean’s opus Lawrence of Arabia. “Ridley and I are both Lean fanatics,” said Lindelof. “and it seemed appropriate thematically.”

“David seems to have some fascination with that film and the character Lawrence,” Fassbender adds, “and I always attributed it to the fact that Lawrence has got a very clear vision and he’s very pure in his pursuit of it. There’s not much questioning. He’s a very decisive character, and I think David sees elements of that in Shaw as well. That’s why he finds her so fascinating. He’s also an outsider like David; he’s an Englishman, but he’s not accepted really by the English or the Arab nations, so he’s kind of somewhere in the middle.”

“He’s got a life history of his own,” Fassbender told Time in 2012. “It’s just probably not relationship-affected. A lot of the time doing the biography is interesting because you can think about what was the character’s relationship with other kids in school, with parents, all that sort of stuff, but David was a programmed entity obviously. So it’s more about how his programming has stayed intact. Are his objectives truly programmed objectives, or has he started to develop his own motivations?”

“While the rest of the crew is in suspended animation, David is enjoying himself, tinkering with the ship’s many technical wonders,” Fassbender explained in 2012. “And like a child, David enjoys watching the same movie over and over again. Additionally, David’s views on the human crew are somewhat child-like. He is jealous and arrogant because he realizes that his knowledge is all-encompassing and therefore he is superior to the humans. David wants to be acknowledged and praised for his brilliance, yet nobody gives him the time of day.”

Most of the crew do seem disinterested in David. Vickers seems to begrudgingly tolerate his presence. Despite claiming David as a son, Weyland dismisses him as nothing more than a conglomeration of inorganic pieces and personal ingenuity (Fassbender commented that “It’s all about Weyland. He is the creator, you know? So when he goes ‘The son that I never had,’ it’s not because he has affection for David, it’s that he has such affection for himself and self-affirmation that he created this.”) Similarly, the supercilious Holloway treats him as an object of amusement. “I think synthetic life is inevitable,” Marshall Logan-Green told i09 in 2012, “and along that line bigotry and racism (if you will) will be inevitable as well. Although I can’t approach a role thinking of [my character] as a racist or a bigot. Certainly now I can look back and explain his disdain for Michael in that way.”

There are interesting parallels here between David and Aliens’ Bishop. Aside from the similarity between David’s wandering the Prometheus ship and Bishop’s scripted introduction (where he roams the Sulaco as the Marines lie in hypersleep) Lance Henriksen also frequently referred to Bishop as being “child-like” and how he was often hurt by how others receive him (one version of the script details that Bishop looks “wounded” when Ripley rebuffs his kindness.) “When I did Bishop,” Henriksen explained, “I was using the fact that I was 12-years-old. I was using my 12-year-old emotional life and thought of myself as a black kid in South Africa. That if I made a mistake anything could happen. So, that’s what I was using through that whole role. There was a certain innocence about Bishop that I created that way. And of course when you’re 12 you forgive adults because you know you’re going to outlive them.”

On David’s poisoning of Holloway, Lindelof explained, “That’s his programming. In the scene preceding him doing that, he is talking to Weyland (although we don’t know it at the time) and he’s telling Weyland that this is a bust. That they haven’t found anything on this mission other than the stuff in the vials. And Weyland presumably says to him, ‘Well, what’s in the vials?’ And David would say, ‘I’m not entirely sure, we’ll have to run some experiments.’ And Weyland would say, ‘What would happen if you put it in inside a person?’ And David would say, ‘I don’t know, I’ll go find out.’ He doesn’t know that he’s poisoning Holloway, he asks Holloway, ‘What would you be willing to do to get the answers to your questions?’ Holloway says, ‘Anything and everything.’ And that basically overrides whatever ethical programming David is mandated by, [allowing him] to spike his drink.”

Logan-Green chipped in that, “My definition of a robot, or at least a self-sustained robot, is to put together information. As much information as possible and data. To build on data. The only way they’re going to grow is to build on data. You meet David collecting data instantly. I think he probably hit a wall (so to speak) with this mission. They all hit a wall, at first, with this mission. And going back to his father, Weyland, and he’s told to ‘try harder.’ I think he understands that he will have to sacrifice a human life in order to achieve that collection of data.”

Prior to the release of the film Ridley teased that it may feature two androids. Speculating fans immediately zeroed in on Vickers, whose costuming and seemingly robotic poise singled her out from the rest of the cast. “Yes, she does look like David,” Lindelof told mtv. “Yes, this was intentional. What better way to piss off your daughter than to build the male equivalent of her?” Vickers’ scorn for David is evident throughout the movie: first, in a brief cut when Weyland describes David as being like the son he never had, and later, and far more obviously, when she slams him against the wall in frustration as David and Weyland plot without her.

As for David’s future, Lindlof told Time that by Prometheus’ end he has aligned himself with Shaw. “I think they’re going where she wants to go. His fundamental programming has been scrapped. Weyland [the man who built and programmed him] is dead and so now his programming is coming from God knows where. Is he being programmed by Elizabeth, or is it his own internal curiosity now that Weyland isn’t telling him what to do any more? He’s always been interested in Elizabeth, remember that: He’s watching her dreams when she’s sleeping in much the same way that he watches Lawrence of Arabia. He’s a strange robot that has a curious crush on a human being, and when Weyland is eliminated, I think he is genuinely interested in what she’s interested in. He reaches out partly for survival, but partly out of curiosity, and I think he’s sincere that he’ll take her wherever she wants to go.”

As for Ridley’s thoughts on the sequel, “You’ll probably have to go with Shaw and David – without his head,” he told Yahoo in 2014. “Find out how he gets his head back on!”