Though Burbank, California, lies only a few miles from the epicentre of the Western film world, it seemed all too far away for the adolescent Ron Cobb. His parents had moved there from Los Angeles in 1940, when Cobb was three years old, in search of a better life promised by the area’s mid-30’s property boom – when the Cobbs relocated in 1940 the city’s population stood at 34,337; by 1950 it would rocket to 78,577. But a middle-class life in a burgeoning Burbank appeared to Cobb to be “bleak and unexciting.”

He saw worse ahead of him, remarking that, “The future held even less promise,” but fortunately he had an escape in his nascent imagination: “I began to notice out of the corner of my eye distant vistas of fantasy, of a world out there glimpsed through the wonderful window of television and E.C. comics. I daydreamed and nurtured my fantasies, and to make them more real I drew. At the same time I became introverted, a terrible student, and waited for something to happen.”

It was science fiction that provided inspiration and spurred Cobb’s enthusiasm for the wondrous. “When I was a little kid I would sit out in the back yard,” Cobb said in 2015, “and I swear I could see people signalling me from the moon. And I knew it was important somehow, but you know, you might say I had a science-fictional childhood, because I always thought about science as adventure, nothing more than adventure, and when it started to appear in movie pictures I was transfixed. I said, ‘I want to do that somehow.'”

Cobb found like-minded friends at Burbank High School with whom he formed C.D. Inc. (the C standing for Cobb, and the D for co-founder Tad Duke), a small club whose members held common interests in pranksterism, atheism and sci-fi — their first official club act was a trip to see War of the Worlds (1953). The group also busied themselves creatively by drawing and conceptualising a fictional history of fictional European country Donovania, along with its fictional prince, Chesley Donavan (apparently named after Cobb’s early influence Chesley Bonestell, whose 1949 speculative sci-fi book The Conquest of Space can be seen in C.D.’s hangout.) Chesley Donavan retroactively became the namesake of the group, with C.D. reconfigured into the ‘Chesley Donovan Science Fantasy Foundation’, which was, according to Cobb, “a deliberately pompous and satirical name for a group of introverted and eccentric students.”

“Our mutual fascinations with science, astronomy, philosophy and theology kept us together until we were in our early twenties,” he explained. “Our involvement in C.D. drew each of us out of our introversions, while we nurtured and entertained each other.”

Ron Cobb, far right, with C.D. in 1954. The group crafted their own uniforms and insignias.

After graduating from Burbank High School in 1955 Cobb, having been a poor student with an aptitude for art and imagination, sought work at Disney, who had opened their lot in Burbank in 1940 on the proceeds from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937). “I had always been fascinated by Disney and deeply influenced by Fantasia. The studio was clearly advancing the art of film animation, in those days, and I was very excited about being a part of it.” After spending two years working as an in-betweener and breakdown artist (notably on Sleeping Beauty, released 1959) Cobb realised that many of the animation giants and geniuses that had attracted him to the field had “retired or died off” and, after being let go by Disney, he decided to seek out opportunities in live action film. “I just didn’t feel like waiting 30 years to become an animator,” he told Starlog magazine. But first was a series of odd jobs and a stint in the US Army and a brief posting in Vietnam.

“I was a prime target for the draft,” said Cobb. “I had to decide whether to evade it as most of my friends had done, or become a member of the military, one of the truly evil institutions of the state, according to the tenets of C.D. This became my great confrontation/escape. I allowed myself to be drafted. It confirmed that my basic anti-militarism was correct, but let me recognize some of my prejudices were unfounded. I gained confidence in the army, but I hadn’t reckoned on spending a year in Vietnam.”

It was during the turbulent Sixties and specifically within the American counterculture that Cobb first found himself attracting artistic acclaim. His political cartoons, at first rejected by Playboy but disseminated through the underground newspaper The Los Angeles Free Press, presented future visions of the ultimate law and order state, the destruction of the American landscape and dark lampoons of Cold War-era doctrines like M.A.D.

One early fan was a USC film student from Missouri named Dan O’Bannon, who reached out to Cobb after appreciating his work in the underground presses. “[Dan] had been following them and had wanted to meet me,” explained Cobb. “We shared an enthusiasm for film, science fiction and filmmaking.” O’Bannon and Cobb’s lives would not intersect again for several years, and in the meantime the artist kept penning celebrated political cartoons that were widely redistributed.

Ron also dabbled in science-fiction and fantasy illustration, drawing covers for Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine including images of Lon Chaney Jnr. and Bela Lugosi’s Frankenstein and Wolfman, two-headed golems, the hunchback of Notre Dame and bulb-headed alien beings. He also provided the cover art for San Franciscan rock band Jefferson Airplane’s 1967 album After Bathing at Baxter’s, (Cobb’s involvement with musical endeavours continued throughout the following decades; he won an MTV music video award in 1986 for his art direction on ZZ Top’s Rough Boy.)

His political work continued to attract acclaim and was showcased in an issue of Cavalier magazine that called him ‘The Toughest Pen in the West’, though Cobb denied being a political cartoonist (“because politics is too superficial”) preferring instead to be called a ‘social commentator’. “But whatever he calls himself,” Cavalier read, “he’s the only artist we’ve seen recently who has the force of conviction, the draughtsmanship, the intelligence and the necessary harsh insight into these harsh times to be a cartoonist in the great tradition.”

But Cobb was becoming disillusioned. He began to notice clichés and recycled content in his peers, and then recognised it creeping into his own work. An artistic block came over him. “I couldn’t paint or draw or think straight. I couldn’t snap out of it. I couldn’t finish anything. I was taking amphetamines. It was really an awful time. And I didn’t know what it was.” Cobb would later reflect that, “I had truly become sloppy with the content of the cartoons while conversely, growing in my attraction to the film medium. It wasn’t an interest in animation that pulled me. My two years at Disney taught me that animation lacked spontaneity. It was the writing, and possible directing, of live action short films or maybe features that intrigued me now.”

A break came when he received a phone call from Robin Love of the Australian Aquarius Foundation, the ‘cultural wing of the 170,000 strong Australian Union of Students’ that primarily helped organise university festivals and counter-culture events. Cobb recounted that Robin had told him that his “cartoons [were] very well-known here” among the Australian counter-culture, and “would [he] be interested in coming to Australia?” Still in a slump in the States, his answer was enthusiastic: “I said, ‘Yes, I’ll come! I’ll come!'”

Cobb’s political cartooning however earned him the scorn of Australia’s Liberal government, who made attempts to ban him from visiting and touring universities, but thanks to Love and the AUS his Visa was not revoked and the tour commenced with protest singer Phil Ochs in tow (and occasionally supported by The Captain Matchbox Whoopee Band). “I discovered a country on a human scale: unpretentious, hardy and social,” Cobb said of his tour. “I began to come out of a non-productive, post-sixties slump which had lasted two years. The exuberant and colourful political scene intrigued me, the air of anticipation of a change in government after over twenty years of conservatism was infectious.” He certainly was not missing the American counterculture. “It should be said,” he clarified in 2005, “I never identified that much with the counter-culture, the new left or ‘The Sixties’. I fully expected flower power to wilt and teach-ins to teach out. Some of what happened was partially effective like the women’s movement, but most of it was too faddish, emotional and self-indulgent (read, American) to really fit the complex mix of world events and thus, change things in all the intended directions.”

At the end of his stay in Australia, Ron and Robin moved in together, married, and moved to Los Angeles in ’73, living on Robin’s dime while Cobb sought involvement in the film industry. “I never expected Ron to make any money,” Love told the LA Times in 1988. “Ron could have been doing everything he wanted to do a lot sooner if he had hustled. But he is not an ambitious person.”

Ron’s first foot into film came way of old acquaintance Dan O’Bannon, who was toiling to assemble his student film Dark Star with director John Carpenter. “I met Dan some years back because of his interest in fantastic films, then didn’t see him again for a number of years,” said Cobb. “He contacted me next when he was in the middle of Dark Star, and wanted to know if I’d be interested in giving him some of my comments on it. When I got there, he had an exterior design for the spaceship, and I started suggesting things.”

“I tried to reach Cobb to get him to design the whole film, but he was unreachable,” said O’Bannon. “For weeks his phone rang without an answer, and then it was disconnected, and then I got his new unlisted number but it was invariably answered by one of the girls who were living with him, who always told me he was out. It was impossible. It took another year and a half to track him down and get him to agree to design us a nice, simple little spaceship for our simple little movie. Finally, one night about ten pm, Carpenter and I drove over to Westwood and roused him out of a sound sleep. He was hung over from an LSD trip and I felt kind of guilty, but I had to have those designs. We took him over to an all-night coffee shop and fed him and got him half-way awake, and then he brought out this pad of yellow graph paper on which he had sketched a 3-view plan of our spaceship. It was wonderful! A little surfboard-shaped starcruiser with a flat bottom for atmospheric landings. Very technological looking. Very high class stuff.”

The brief collaboration was encouraging enough for O’Bannon that he kept Cobb vigorously in mind for future projects. When he was hired by Alejandro Jodorowsky to oversee the special effects for Dune, he recommended that Jodorowsky add Cobb to his artistic stable, which already included eminent artists like Chris Foss, Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, and HR Giger. “I tried to get Cobb on to Dune,” O’Bannon told Fantastic Films in 1979, “but it never worked out.”

“Transatlantic phone calls [to Cobb were] made,” O’Bannon said of the arrangements to get Cobb on board, “and a date is set for Cobb’s transfer to Paris. Cobb and his wife pack their bags, the date arrives, but no plane ticket.” While waiting to officially join the project, Cobb managed to submit designs for the film, but Jodorowsky apparently thought they were too Earth-bound, too realistic, “too NASA.” Still, efforts were being made to fly him out to. “A new date is set,” O’Bannon goes on, “it arrives, and passes. More phone calls. Altogether, Cobb and his wife were packed and ready to get on a plane for about three months. They had terminated the lease on their apartment. This was the position I had gotten Cobb and Robin into when Dune collapsed completely, like a pile of rotten sticks.”

For his part, O’Bannon felt incredible guilt for leaving Cobb in the lurch. When he too ended up back in LA, broke and despondent, he managed to bounce back with a position on George Lucas’ Star Wars and, while there, he put in a word about Cobb. Allegedly, Lucas, visiting his friend John Milius, saw one of Cobb’s paintings on the wall called ‘Man on Lizard Crossing Over‘, depicting a proto-dewback carrying a mysterious traveller over a desert landscape. “Lucas said that he had the idea [for the dewback design] before he saw the painting,” Cobb said in 2015, “and Milius said, ‘No you didn’t. I remember the night you came here and pointed at the wall.'” Cobb laughed, “But that’s Star Wars for you!”

Either way, the image must have tapped into Lucas’ own imaginative ideas for his space opera, and he agreed to a meeting with Cobb on O’Bannon’s recommendation. “It was Dan who was working on this crazy space opera that we had all heard about,” said Ron. “It was costing so much money and George [Lucas] was convinced it was going to be a flop because the budget had blown out so much.”

Some of Ron’s designs for Star Wars‘ Cantina aliens.

“George had been unhappy with what they had shot, which was mostly people with bits of foam stuck to their face as the aliens. So he called me in and I sat down across from him with these pages of designs where the aliens were more biological. He looked at each one and went, ‘Okay, okay, okay. These are good.’ When I left the meeting all the production staff were waiting at the door. They asked me what he said, I told them, and they were all flabbergasted. One of them said, ‘That’s the most excited he has been about anything!’”

~ Ron Cobb, ninemsn.com, 2014.

Dan rushed to Cobb again when his long-gestating screenplay for Alien was picked up by Brandywine Productions and then greenlit by Twentieth Century Fox. “The first person I hired on Alien,” said O’Bannon, “the first person to draw money, was Cobb. He started turning out renderings, large full-colour paintings, while Shusett and I were still struggling with the script – the corrosive blood of the Alien was Cobb’s idea. It was an intensely creative period – the economic desperation, the all-night sessions, the rushing over to Cobb’s apartment to see the latest painting-in-progress and give him the latest pages.”

“So basically, it’s all been Dan,” said Ron. “He went to work on Star Wars and Dune, and each time he tried to get me on those projects. But since I didn’t have a great deal of film experience, producers were quite reluctant to hire me—except for George Lucas, who’d been familiar with my cartoons … Then Dan finally sold his script, and Alien was underway. He suggested that they use me, and the same problem arose, but I was taken on sort of a trial basis for about seven months in California, before the entire production moved to London.”

“We were put through shed after shed after shed,” said Chris Foss, whom O’Bannon had hired for Alien after having previously met in Paris while working on Dune, “and they were going through director after director after director.” Cobb himself told Den of Geek that “I soon found myself hidden away at Fox Studios in an old rehearsal hall above an even older sound stage with Chris Foss and O’Bannon, trying to visualize Alien. For up to five months Chris and I (with Dan supervising) turned out a large amount of artwork, while the producers, Gordon Carroll, Walter Hill and David Giler, looked for a director.”

“And he was doing some incredible stuff,”O’Bannon continued. “Wow! I was really happy during this period, seeing the movie appear under Cobb’s fingers. Of course, we usually had to go over and sit on his back to get him to do any work -otherwise he would just party on with his friends- but how beautiful were the results.” Cobb accompanied O’Bannon to England when Alien’s production went into full swing, having been personally recommended to director Ridley Scott by O’Bannon. “O’Bannon introduced me to Ron Cobb,” Scott told Fantastic Films in 1979, “a brilliant visualiser of the genre, with whom he’d worked on Dark Star. Cobb seemed to have very realistic visions of both the far and near future, so I quickly decided that he would take a very important part in the making of the film.”

“I made the two-hour round trip [to the studio] with [Cobb] every day in a miniscule red Volkswagen Golf,” said O’Bannon. “I hate to drive, so the first time I got behind the wheel I took off for London at about 70 mph and made it back in record time, through the most horrendous commuter crush and with all the traffic going the wrong way as well. Toward the end there, Cobb actually screamed, and cried out something about how I was going too fast. The next morning when he picked me up in the Golf, he told me firmly that he would be doing all the driving from here on out, so that took care of that.”

Cobb with Giger at the King’s Head Pub, Shepperton, England, 1978.

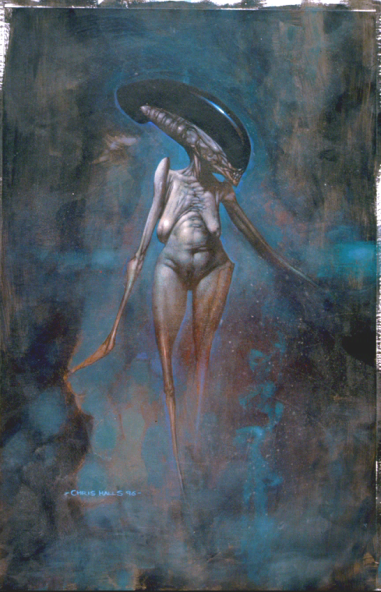

Cobb, along with Foss, was tasked with realising the human elements of the film, but he also took a crack at the Space Jockey, Alien, and the Alien temple from O’Bannon’s version of the screenplay. In Cobb’s conception of the Alien temple, a hieroglyph depicts, in a Mayan-esque fashion, an insect-like creature prone on its back as another being erupts -depicted in glorious fashion- from its midcentre. Above the new lifeform’s head is an image of an Alien egg, deified and ensconced within an aureola. The pyramid was ultimately cut due to budgetary and time constraints, and Giger was tasked with its design when the silo was incorporated with his derelict craft (which Ron also took a shot at). Ron’s concepts for the planetoid, which hewed close to O’Bannon’s Mars-esque description in his screenplay, were also ‘ignored’ by the production when the planetoid was given a grey colour scheme (Dennis Lowe’s early effects work for the planet depicted it as a turbulent orange and red swirl, akin to the surface of Jupiter.)

Though O’Bannon loved Cobb’s other designs for the Alien and derelict ship, they were lacking what only Giger was able to provide: a tangible nightmarish quality. Cobb’s Alien was rejected in favour of Giger’s almost from the get-go. “I’m afraid Ron Cobb’s ego was sorely wounded when he didn’t get to do the monster,” O’Bannon told Cinefex in ’79. “He was endlessly frustrated because he could design aliens without number and they were all convincing and all unique and all startling to look at … His designs just weren’t as bizarre, or as bubbling up from the subconscious as the stuff Giger was doing. Cobb’s monsters all looked like they could come out of a zoo—Giger’s looked like something out of a bad dream.”

But Dan did love his concept for the Space Jockey, which he described as “Just perfect! Very small jawbone – no teeth to speak of. Of course, I expected it to look horrible when you first see it in the film; but if you looked at it a bit closer you’d discover that it didn’t have the large teeth or mandibles or any of the other things that are characteristic of a carnivore – and then maybe you’d begin to imagine it as some totally nonviolent herbivorous creature sailing around in space.”

Ridley however was enamoured with Giger’s Space Jockey, and elected that the other conceptual artists focus on other areas of the film, namely the Nostromo, which had to have all the appearance of a functional and plausible 22nd century ship, but also had to convey the idea of being a haunted house, or castle; its comm towers and satellites would have to evoke a conglomeration of cathedral spires and other Gothic shapes. “I wanted the ship to look like a gothic castle,” Cobb explained, “but resisted that approach—it might have been a bit too much … I grew up with a deep fascination for astronomy, astrophysics, and most of all, aerospace flight. My design approach has always been that of a frustrated engineer (as well as a frustrated writer when it came to cinema design). I tend to subscribe to the idea that form follows function.”

Cobb, who was later quoted in the Book of Alien explaining that he preferred to “design a spaceship as though it was absolutely real, right down to the fuel tolerances, the centers of gravity, the way the engines function, radiation shielding, whatever,” found himself struggling to maintain a balance between his aesthetic preferences and Ridley’s more fantastical ideas. “They pressured us a lot to bend the technology to have a somewhat similar look to Star Wars,” said Cobb. “Sort of half-believable, but rather highly stylized—or perhaps a better word would be romanticized. The interior of the ship finally looked like a deco dance hall, or a World War II bomber, and a genuine projection of what a space ship of the future might really look like—or a combination of all of them. The theory was to give Alien more of a horror look, but I never personally agreed with that, and I didn’t have as much influence as I’d like to have had.”

Cobb’s strident rationalism impeded his attempts at the alien technology. “The only problem was that he was a rationalist,” O’Bannon explained. “I noticed this when we first started designing the picture. All these different things he as doing were coming out so well that I decided to have him take a crack at the derelict spaceship. But when I asked him to come up with an irrational shape he got very disturbed. He couldn’t handle that. He kept coming up with convincing technology for a flying saucer or some other kind of UFO.”

For his part, Ridley also found that his flashes of artistic license caused consternation with Cobb’s more realistic design philosophy. For one, Cobb insisted that every detail on the ship be accounted for: how doors opened, where the screws went and how the pistons pumped, etc. Scott however tended to find himself fighting to retain ‘illogical’ images like the ‘rain’ during Brett’s death in the Nostromo’s leg room, reconciling it to dissenting voices as condensation from within the ship. He found similar resistances when it came to getting across his ideas of the Nostromo’s outer shell. “The concept was to have the hull covered with space barnacles or something,” said Scott. “I was unable to communicate that idea, and I finally had to go down there and fiddle with the experts. We gradually arrived at a solution.” It seemed that removing any ‘space barnacles’ was a concession Scott made to the artists. “I would have liked to see it covered with space barnacles or space seaweed,” he told Fantastic Films, “All clogged and choked up, but that was illogical as well.”

Cobb meanwhile figured that the resistance to exploring the stark reality of space travel came from disinterest or inexperience on the part of the production. “There’s a certain awkwardness in the naturalistic portrayal of the space flight,” he said, “Partly because most of the people involved in this film had never made one before. They didn’t understand what they were getting into, and were put off by concepts like no sound in space, and all the gravitational effects.”

“When I met Ron, he was very adamant that they were very realistic. He wanted a heat shield on the underside of the Nostromo lander. He wanted a contrast between the smooth underside of the heat shield and the detailed upper surface. However this was not to be. Our instruction was to encrust the whole craft. When it came down, we weren’t seeing a craft come through an atmosphere; there was no re-entry. Ron was concerned that it should be there if that type of action was present. Ron is very much into the believability of things. He created wonderful background histories about his designs.”

~ Bill Pearson, Sci-Fi & Fantasy FX magazine, Aliens Collector’s Issue (#48)

“I’ve always done future designs as though they’re real,” Cobb said, “and I’ve found the more realism you put into it, the more original they look, and most of the time you don’t do that you’re just recycling a lot of silly props from every idiotic movie that’s ever been made. We just covered the walls with drawings and, slowly but surely, Alien emerged.” The amalgamation of all these various aesthetics allowed for Alien to present a very believable environment with little bearing on issues like faster than light travel or time dilation: instead, the Company’s armada of commercial ships flit from one side of the galaxy to another in short spans (the film tells us the return journey to Earth from the planetoid would take “Ten months”) and the crew do little to expositise on the ship’s technology.

In the end, the Nostromo’s design was not coalesced from various concepts by its artists, but by frustrated technicians tired of waiting for something to build. Cobb explained that “Brian Johnson, the special effects supervisor under pressure to build the large Nostromo model, went into the deserted art department and, out of frustration, grabbed all the Chris Foss designs off the wall and took them to Bray Studios. There he would choose the design himself in order to have enough time to build the damn thing … Well I soon found out that Brian found and took all of my exterior design sketches as well. About a month later I was told that Brian had used my sketch, ‘Nostromo A’, as the basis for the model, even to the extent that it was painted yellow. Ridley found the colour a bit garish and had it repainted grey.”

Some of Cobb’s interiors were replicated from the page directly onto the screen, so his sketches for a passage on the Nostromo’s A deck–

–was rendered faithfully as below:

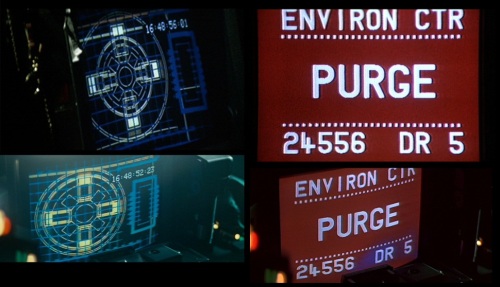

Cobb’s creative contributions extended beyond the look of the film: he also inspired O’Bannon to give the Alien acidic blood, coined ‘Weylan-Yutani’, and crafted with costume designer John Mollo all manner of fictional corporate insignias and emblems intended to give the film additional depth, even though the majority of their work would not be seen or even referenced on screen.

“One of the things I enjoyed most about Alien was its subtle satirical content,” explained Cobb. “Science Fiction films offer golden opportunities to throw in little scraps of information that suggest enormous changes in the world. There’s a certain potency in those kinds of remarks. Weylan-Yutani for instance is almost a joke, but not quite. I wanted to imply that poor old England is back on its feet and has united with the Japanese, who have taken over the building of spaceships the same way they have now with cars and supertankers. In coming up with a strange company name I thought of British Leyland and Toyota, but we obviously couldn’t use Leyland-Toyota in the film. Changing one letter gave me Weylan, and Yutani was a Japanese neighbor of mine.” The Company would be called Weyland-Yutani in the following movies, with the ‘d’ added sometime during Aliens’ production by Cobb for an unspecified reason – perhaps it was an error, or he was no longer shy about the ‘Weyland/Leyland’ allusion.

For the Company’s logo Ron figured that “It would be fun to develop a logo using the W and Y interlocking. We tried a lot of variations and came up with some very industrial looking symbols, which were to be stenciled all over the ship. By that time though Ridley was already set on using the Egyptian wing motif. We tried some combinations, but they didn’t really work. Weylan-Yutani now only appears on the beer can, underwear and some stationary, so the joke sort of got lost.” Though it’s not obvious at a glance, Cobb’s Egyptian motif logo appears on virtually every piece of equipment on the Nostromo, including dinner bowls and coffee cups. The crew wear blue Weylan-Yutani wing emblems on their chests, except for Kane, who wears a silver patch, and Dallas, whose gold patch is possibly coloured to denote his captaincy.

Cobb and Mollo also conceived a pseudo-historical backdrop over which Alien takes place, creating space corporations like Farside Lunar Mining and Red Star Lines that went virtually unseen and absolutely unmentioned in the film, but which, for its creators, helped flesh out the unseen universe permeating the movie frame. Cobb also designed a flag for the United Americas -the union of South, Central and North America which took place in 2104, at least in the Alien universe- which is essentially the stars and stripes with one unitary star rather than fifty.

“I think Dan will be pleased. You know, for a while they strayed pretty far from his original concept, but eventually they found their way back into the primary science-fiction/horror framework. By the time the principal photography was finished, everybody was looking forward to seeing how all the pieces fit together. At the very least, Dan won’t have to sleep on anyone’s sofa for a while—I hope.”

~ Ron Cobb, MediaScene, 1979.

“On the whole, I’m pretty happy with the way my ideas were eventually realized,” Cobb told MediaScene on the film’s release. “It was fascinating to watch the process all the way through, even some of the set dressings. I was pleased with things I had a fair amount of control over, but those I didn’t oversee were a little disappointing … Then there was always surprising contributions from draftsmen and other people who would occasionally design a set that would turn out very, very well. It was a mixed bag of many styles and many approaches.”

Alien’s success unlocked doors that had been frustratingly barred to Cobb for more than a decade and the eighties saw a boon for him: he designed Conan the Barbarian’s Hyborian age in John Milius’ film of the same name as well as Conan’s weaponry and armour. He was a production artist on Raiders of the Lost Ark, contributing concepts for the Nazi airplanes, designed the interior of the Mothership in the Close Encounters special edition, and he created the initial concepts for the time-travelling DeLorean in Robert Zemeckis’ Back to the Future.

Cobb in costume for his cameo appearance in Conan the Barbarian.

While working on Conan the Barbarian in Spain Cobb would visit Steven Spielberg, who was down the hall working on Raiders of the Lost Ark. “I first met Spielberg when I was working on Alien,” Cobb told bttf.com. “At one point Spielberg was considered as a possible director for the original Alien. It was just a brief thing, he could never work out his schedule to do it, but he was interested.” With Spielberg Cobb would find himself able to express his directorial ambitions. “I would suggest angles, ideas,” he said, “Verbalize the act of directing — ‘Let’s do this and do that, and we could shoot over his shoulder and then a close-up of the shadow.’ Steven used a lot of my suggestions. I was very flattered.” One day, Spielberg told him, “I think you can direct. I want to back a film for you.”

The film, a sequel to Close Encounters of the Third Kind built around a nebulous idea that Spielberg had about the Kelly-Hopkinsville UFO Incident, was quickly nixed when the family at the centre of the event threatened to sue. The desire to make the film remained, but it was in need of a new story and characters around which to frame the tale of a terrifying alien visitation. Cobb then pitched a concept to Spielberg and John Sayles wrote the script, titled Night Skies. However, Spielberg hired screenwriter Melissa Mathison (soon to be Harrison Ford’s wife of nineteen years) to rework the story with a new title: E.T.

“I realized that Steven had changed the script a lot,” said Cobb. “He went back to a story he had told me about years before: An alien is abandoned and protected by a little boy. It wasn’t scary anymore. It was kind of sweet. Finally, [Spielberg producer] Kathleen Kennedy called to say, ‘Steven doesn’t know how to tell you this, but E.T. is very close to his heart, and he wants to make that his picture next year, and he’s decided to direct it himself. So what we would like to do when you get back is work out another picture for you. Because Steven really wants to back your career.'”

In truth, Cobb was relieved: the new script was far too different from his pitch, far more “cutesy”, and the final film itself too saccharine for his tastes. Spielberg did allow him a cameo in the movie as one of E.T.’s doctors (“I got to carry the little tyke out”) as well as a generous take of the resulting profits. The first cheque to drop through the door amounted to $400,000. “Ron spent all those years doing cartoons and not getting paid,” Robin Love told the LA Times, “and then he gets a million for not doing anything. Friends from Australia always ask, ‘What did you do on ‘E.T.‘?’ And Ron says, ‘I didn’t direct it.'”

In 1985 James Cameron enlisted Cobb to design Hadley’s Hope, the Atmosphere Processor, and some of the Colonial Marine gadgetry for Aliens. Though many Alien stalwarts returned for the sequel (including Brian Johnson, Adrian Biddle, and stuntmen like Eddie Powell among others), Cobb was the sole conceptual artist to provide continuity with the first film.

“Jim always had a strong vision with all his scripts and features,” said Cobb. “However, he was always open to good ideas from just about anyone (but they had to be damn good ideas). If I could submit an idea or design that collaboratively enhanced his vision (something I always endeavored to do on any film project) Cameron was quite receptive.”

Cobb found working with Cameron fruitful and straightforward enough (“his talent spanned smoothly from science to art, a mix I have always aspired to,” he told JamesCameronOnline) that he also drew concepts for The Abyss (1988) and True Lies (1994). He continued to design for film throughout the nineties and the new millenium, with Total Recall, The Rocketeer, Schwarzenegger’s late nineties effort The 6th Day, the animated Titan A.E., Joss Whedon’s Firefly and Neill Blomkamp’s District 9 being added to his already impressive oeuvre.

Ron Cobb’s contributions to science fiction and fantasy films from the 70’s onwards has been profound, though he remains relatively obscure in comparison to celebrated figures like Ralph McQuarrie or Stan Winston, and even his early cartooning career remains an often unknown element to fans of his film work — probably due to the immense success of his reinvention from an underground social commentator to a visualiser of some of the most evocative and memorable science-fiction environments, creatures and contraptions of the last four decades.

Ron Cobb at the Offis eClub Xmas Party, December 2015.