“Then the friendless man wakes up once more, sees before him fallow waves,

sea-birds bathing, spreading their feathers, frost and snow falling mingled

with hail. Then the heart’s wounds are harder to bear, sore in the wake of loved ones. Sorrow is renewed.”

~ The Wanderer, author unknown, circa 8-10th century C.E.

This post does not delve into the making of Alien 3 in any particular way, but instead focuses on an element in the film that I personally find interesting – the concept of an apocalyptic ecclesiastical order suddenly imperiled by an eldritch terror in some backwater of space. Mixing a Medieval aesthetic with Alien might not seem immediately congruous, but they do manage to neatly intersect. The Dark Age influences in Alien 3 are an inheritance from Vincent Ward, who wrote and was slated to direct one iteration of the script. In his story the hell of Fiorina 161 is instead a heaven called Arceon; a jerry-built orbital colony with a population of 350 political prisoners who, in their exile from Earth, have all converted to a Ludditic monasticism. When David Fincher came aboard he pushed for a grimier, more traditional environment, and so the script was rewritten, setting the action on a prison planet inhabited by a skeleton crew of convicts and custodians. Though Vincent Ward’s vision of a Medieval-themed Alien film was not realised his tenure on the project left residual elements that inform the film as it was finally made and are certainly worthy of examination…

It was once commonplace to believe that as the world neared the first millennium it would begin to display signs of decline or decay – clear evidence of the impending Doomsday. Fiorina itself is a wasteland of creaking cranes, black waves, grey cliffs, flinty beachheads, abandoned tractor cabs and shacks and a creaking webwork of chains and pulleys. In this universe corporations have long usurped government institutions as world powers, the wonder of space exploration has become the monotony of long-haul truck driving, and the discovery of extraterrestrial life is not revelatory, but destructive. To the outcasts stranded there, a Fiorina sunset must look like the dying heat at the end of time.

The implied but undefined backstory to the Alien series suggests a human civilisation that has reached out into the depths of the universe yet cannot tame its most selfish and destructive qualities. A final note on the stagnant state of the Alien universe: when asked to explain how Ripley could adapt to the technology of 2179 after nearly six decades in cryosleep, James Cameron offered several possibilities, including the fact that “there have been 57-year periods in history where little or no social or technological change took place, due to religious repression, war, plague or other factors”.

The prisoners, with their stubbled domes, prickly demeanors and thrawn appearances, seem as far as you could get from the meek political dissidents of Ward’s script, but his monastic touches were not dropped completely. “This script has retained the look of a religious community,” explained Charles Dance, who played Clemens. “The men have embraced a sort of strange religious cult in this prison … All the costumes are very monk-like, colored in grays and browns. We have these wonderful hooded coats which reach right to the floor, and which are made out of government surplus tents. The look is both monk-like and menacing.”

In Giler and Hill’s October 1990 draft the prison complex retains much of the Wooden Planet’s architectural make-up including wooden beams, windmills and extensive candelight, used to “augment minimal electric light” in the facility. Candles feature heavily in the film’s foraging sequence where the Alien kills Rain and Boggs, and Rex Pickett’s script even features a Candle Room where boxes are stored and the Assembly Hall is known as the Library – as it was in Ward’s script.

Some famous poems from the Early Middle Ages, like The Wanderer and The Seafarer, focus on lonely figures in blasted landscapes, bereft of companionship or warmth, their minds despondent with the knowledge of bodily and earthly decay, their spirits only upheld by a belief in an imminent and glorious posthumous existence. Of all the prisoner characters, Clemens, despite his irreligiosity, fits this Old English melancholic temperament the best. “[Clemens is] very much a loner,” explained Charles Dance, “and not at all popular with the other members of the staff.” His introductory scene, featuring him wandering the bleak landscape alone with his thoughts, could have been lifted from any number of Old English poetry. “Often, at every dawn, I alone must lament my sorrows,” reads The Wanderer. “There is now no one living to whom I might dare reveal my heart.”

Michael Swanton, in his book English Literature before Chaucer, writes that: “Voluntary exile was a familiar ethic in secular life … for many it would seem sufficient to withdraw from the world into one or other burgeoning eremetic communities.” In the same way, Clemens, in shame, shuns any notion of returning to Earth or any other populated colony after his sentence has been served, and elects to bunker down with the close-knit outcasts on Fury. And yet, by his own testimony, he remains an outsider.

A note on Clemens’ backstory: in the film he reveals that his crime was manslaughter via severe negligence. Both pre-shoot scripts by Giler and Hill, from October and December 1990, tell the same story, but Rex Pickett’s January 1991 draft tells us that Clemens euthanised his pregnant wife after an accident put her into a coma. “The authorities gave me a choice,” he says. “The reason I came here is I wanted to go some place far enough away in order to forget.”

Regarding the prisoners and their religion, though their exact tenets are lacking any real exploration in the film, one aspect of their belief system was present in one early draft. When Ripley asks that Hicks and Newt be cremated, Aaron and Superintendent Andrews are wary:

Aaron staring at Newt’s body.

Aaron: The prisoners believe defiling a body is a sin…

Clemens: Yes. When one of our prisoners dies, they want the body whole, so he can be resurrected during the coming apocalypse.

A funeral and cremation for Newt and Hicks is arranged when Clemens warns Superintendent Andrews that the bodies may carry a contagion.

Meanwhile Dillon, the leader, pastor and prophet of the inmates, shares with two other prisoners that the scheduled cremation is completely fine by him so “long as it isn’t one of us,” (prisoner Murphy being shredded in a duct fan must have been particularly troubling for the others to stomach, since it likely quashed any chance of a bodily resurrection.) Dillon tells the other inmates to attend the funeral to collectively “show our respect,” and he even goes so far as to officiate the service. Later in the canteen Ripley learns more about the prisoners’ beliefs:

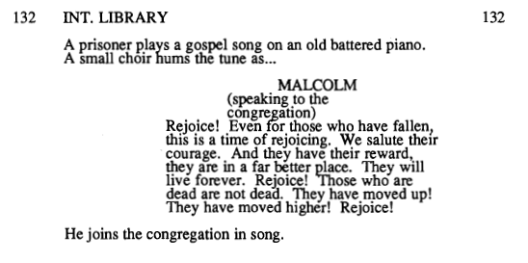

Dillon is the quintessential fiery proselytiser; a Malcolm X type (as you can see, he was even originally named Malcolm in early scripts) his voice is naturally stentorian and his language also heavily apocalyptic. Ine one draft he beats the prisoners for their attempted rape of Ripley and exclaims as he swings, “You will not fornicate! You will not rape! You will live up to your vow! You are too close to heaven to turn around!” In a later script the death of one prisoner makes him comment that “Deep shame fills my soul”; not far removed from the “frozen heart” and shamed melancholy of the Old English exile.

Later, as the Alien closes in, Dillon exhorts his fellow prisoners that “This is what we have been waiting for. This is the sign. This means the last days are near. This is The Beast from the book.” When he peptalks the others into trapping the creature he exclaims that “Those who die first go straight to the promise!” The prisoners then “Roar in approval of Jihad” and await the Alien, the dragon, “The One Who Will Come” from their prayers. “For I will be safe on The Day of the Beast. My body will be taken, but never my spirit. I am ready to be judged!”

Even Ripley cannot talk of the Alien and its implications on the wider universe without invoking religious metaphors. “I get to be the mother of the apocalypse,” she tells everyone when discussing the Queen embryo inside her.

Golic, the Judas of the story if there is one, shares an interesting relationship with ‘The Beast’ (or ‘the dragon’ as he calls it) that owes more to the relationship between Dracula and Renfield than anything particularly Medieval or theologic, though early scripts did feature a religious angle. After the Alien has killed Rain and Boggs he tells Dillon, “You pious assholes are all gonna die … The beast has risen … Nobody can stop it.” He later tells Morse that “I got to see it again. It’s the dragon of God. It’s in the book.”

Of course, I am not claiming that Walter Hill and David Giler or any of the other intermittent writers read any Old English or Medieval works and instilled them into Alien, with the exception of Vincent Ward. What is more likely is the inspirations behind Ward’s story trickled through into the final film through a long process of being trimmed, dressed over, and distilled. Though some of it shines through (most obviously, the religious nature of the prisoners along with some costuming and imagery) most of their deeper implications can only be inferred upon. Alien 3 is a film that is not greater than the sum of its parts. But some of its many constituent pieces, when inspected, can sometimes reveal an embarrassment of riches as well as missed opportunities.

In you are, by any slim chance, interested in Early Medieval/Old English attitudes towards millenarian apocalypticism, I have written about it here.