As we pointed out in the snippets provided throughout Bad Alien Reviews and the letters from Fan Reaction to Alien, 1979, the critical reception that Alien received upon release in 1979 was somewhat mixed: though some prophesied, somewhat understatingly, that the film could perhaps become a cult favourite in time, many reviewers were simply unimpressed with the film’s unapologetic B-movie roots and its sheer single-mindedness. A few others wrung their hands, fretting that the film was indicative of the sickness of both society and its creators (you know, the old “the cinema is our modern-day Coliseum/Grand Guignol” sort of tracts).

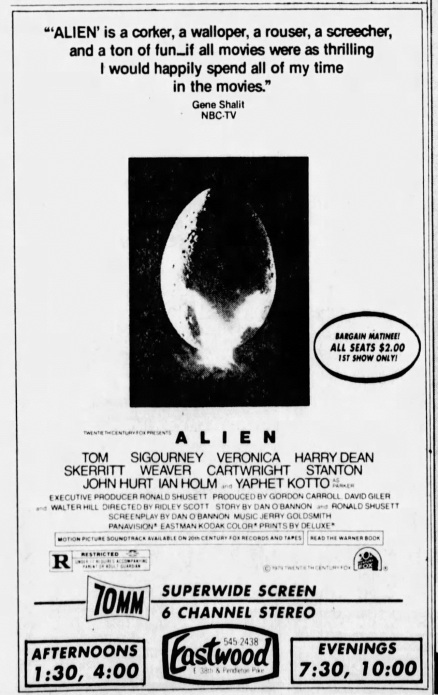

The following are selections from a range of American newspapers that reviewed Alien in the summer of ’79…

Great Galaxy! Won’t these space explorers ever learn?

~ by Dick Shippy

The Akron Beacon Journal

Thursday June 28th 1979.

Ancient mariners could have told ‘em: You don’t mess around with another guy’s spooky space, even if it looks deserted, because you might find what you don’t want to find, and… phht!… there you are, stuck with an albatross, or the plague, or some other scourge of mankind.

But the future voyagers of Ridley Scott’s Alien exist solely for the purpose of locating the horrifying unknown in the deserted mansion of outer space. It means they’re a lot less smarter than ancient mariners, and a lot more commercial.

For if Alien is punctuated by blood-curdling shrieks and screams, there’s at least one other noise it engenders: The clanging of a cash register. Every time The Alien gobbles up one of God’s living creatures, another $8 to $10 million changes hands.

This is not creative filmmaking, but you might make a case for Alien representing a slick mixing of movie metaphors through movie technology.

What is Alien, after all, but a primeval terror (Jaws) expressed in gory special effects, surrounded by the mock-technological gadgetry of outer space hokum (Star Wars) and aimed at reducing, under fearful circumstances, the population of a floating, zero-gravity charnel house (which is only a substitute for any movie house of horrors you could care to mention!)

Maybe director Scott and his colleagues, including scenarist Dan O’Bannon and the special effects folks with their marvellous techniques with flesh and spewing blood (Linda Blair’s vomit in Exorcist being almost tame by comparison), have created the definitive scare-0the-pants-off-‘em, science-fiction monster to date.

But as The Alien had its antecedents —The Thing, the Blob, and let’s never forget the popular Whatchamacallit Which Made Mincemeat of Walla-Walla— so will it have progeny even more petrifying. Isn’t that the true test of American technology!

Before then, though, we’ll have to settle for the hideous business aboard SS Nostromo, sailing from Out There to Back Here. It is a space tug towing an oil refinery through galactic seas — which at least gives us hope they’ll have found a substitute for Iranian oil 200 years hence.

There are seven crewmen aboard SS Nostromo, including the black gang which works the engine room and complains about long hours and low pay (one of them literally black, Yaphet Kotto having integrated space.)

The ship’s captain (Tom Skerritt) and the scientific guru of SS Nostromo insist on poking into a mysterious signal emanating from a seemingly deserted planetoid. If only they would listen to the ship’s resourceful, no-nonsense executive officer (the winsome Sigourney Weaver) who thinks they should not mess around with the unknown. She heeds ancient mariners!

What is found on that planetoid is the wreck of a space vehicle from another galaxy, and what is found in the eerie interior of the wreckage is an egg-like substance (it’s as ominous as Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack can manage) and —PHHT!— the fat is in the fire. The Alien has struck some poor sap!

Now, what form does The Alien take? Let’s say that, initially, it looks like a big chicken liver with tentacles, and the poor sap is wearing this thing like a helmet.

So, back to SS Nostromo where the chicken liver can be lugged inside, in violation of quarantine. It is learned the whateveritis does not bleed; it emits an acid substance. One tough turkey!

Suddenly, The Alien is gone; just as suddenly, it is back again — this time bursting through a crewman’s chest in a bloody froth. And this time it looks like either a small dinosaur or small snake, and it had a voice like Johnny Ray and it’s definitely a challenge for an up-and-coming mongoose.

Well, there’s a cat aboard, but no Rikki Tikki Tavi!

Thereafter, The Alien continues to change shapes, looming larger and larger in the blackness and eventually getting to a size which makes it eligible for the National Basketball Association draft.

And thereafter, amid screams and howls attendant to butchery, Alien plays down-you-go with its cast of seven.

It is gross foolishness and grievous horror-mongering, the grisly nonsense done expertly, maybe, but will the last man out please turn off the projector? We’ve had enough.

If gore is your cup of tea, see Alien

~ by Randy Hall

The Anniston Star Sun

June 24th 1979.Well, summer is here, and it’s silly season at the movies.

Last summer it was Grease and Jaws II. This summer, it’s Alien, hands-down the monster movie with the most revolting monster you ever saw in your life.

Even though it borrows spiffy special effects technology from Star Wars and Close Encounters, the film is put together with all the wit and taste and subtlety of an ax murderer. Still, if it’s screams you want, Alien has got ‘em.

The film is set aboard the Nostromo (name for the Joseph Conrad novel), an outer-space freighter about the size of Manhattan returning to Earth with 20 million tons of mineral ore. The ship is a bit clunky and used-looking, borrowing the ‘used future’ concept from Star Wars.

Awaking from deep sleep is a grousing, non-heroic crew (Tom Skerritt, John Hurt, Veronica Cartwright, Harry Dean Stanton, Yaphet Kotto, Ian Holm and Sigourney Weaver) who are more concerned about their shares in the voyage than investigating a radio signal from what appears to be the surface of Saturn.

But investigate they must, and in one of the film’s more spectacular visual sequences, borrowing from the fantasies of Frank Frazetta’s outer space landscapes, discover an abandoned space ship. There they find the Horror which they bring back aboard the Nostromo, nuch against the intelligent objections of warrant officer Sigourney Weaver.

Alien is the kind of film that can’t be described without giving away too much of the plot. Suffice it that when the monster actually does appear, it sends the audience into gales of laughter — the monster is just so gruesomely, disgustingly AWFUL, especially when it shrieks and goes running off. The rest of the film is spent watching the monster munch down members of the crew like Pop Tarts while they try to kill it.

Is it worth pointing out the improbabilities?

Alien is the kind of film in which people go wandering off alone into dark rooms, disobey rather elementary rules of quarantine, and stop and worry about the safety of pussycats while the monster is chasing them.

Fully conscious of how the filmmaker is manipulating the viewer, one sits in the dark theatre thinking, ‘Oh, get up and run, dummy!’ but glued to the long, slow panning shots of the camera. You never know what is going to turn up at the end of one of them.

Director Ridley Scott, previously known for his art film, The Duellists, has learned his lessons in suspense-making from Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, but hasn’t bothered taking notes on Spielberg’s carefully constructed storyline.

But who cares? It’s summer silly season at the movies.

Faint praise: Alien succeeds in the scare department.

~ by Gene Siskel

The Chicago Tribune

Friday 25th May 1979.A veteran filmgoer friend has been slightly amused at all of the hoopla surrounding the new outer space horror movie Alien. He had head the reports of an usher fainting during a sneak preview in Dallas. He had heard about women at the same screening running up the aisles and out of the theatre in order to throw up in the john.

“I’m amazed,” he said, “that people can get that worked up about a movie, especially when they know it’s supposed to be scary.” That remark may explain it all. Knowing that a film is supposed to be scary may put people in such a frenzied state of mind that if you showed them Bambi they still might blow lunch. That was certainly the case with the hyped-up crowds waiting to see The Exorcist a few years ago. People were hyperventilating in line, all in an attempt to stay cool.

Which is not to say that Alien —or The Exorcist, for that matter— is some kind of cheap, vulgar movie that is trying to out-gross every other film ever made. On the contrary, Alien in its many quiet moments is an extremely cool, even droll, commentary on the banality of space travel. The point of the picture: Just as there is random evil on Earth, so will there be random, indifferent evil in space.

The story is set a decade from now. Seven Americans (five men, two women) are travelling through space on a commercial tug, hauling a huge refinery being them. Their mission is to find intergalactic sources of fuel, and they go about their business in a lacklustre, routine office staff manner. In fact, as the picture opens, a couple of the guys are complaining about their wages (this is refreshing to see. Frankly, I’ve always been peeved at science-fiction movies that suggest the future will be radically different from today. My guess is that life in the next hundred years will be disturbingly similar to life today.)

Anyway, all is routine aboard the ship until its computer, a micro chip off the old HAL, suddenly receives a signal that eventually turns out to be a warning. The computer is receiving a signal from somewhere other than Earth, and it is a primary mission of the crew to investigate all such extraterrestrial transmissions.

What follows is that the crew touches down on a planetoid in order to investigate the transmission and winds up encountering a space monster.

The monster cannot be reasoned with. It’s not Darth Vader from Star Wars. It’s not Ming the Merciless from Flash Gordon. It’s not even HAL the Computer from 2001. This monster, the alien of the film’s title, is an organic mass that grows and grows. It cannot be talked to, charmed, persuaded, or even hit over the head. It can only be destroyed. In a way, I suppose, this monster is like a number of space monsters from sci-fi films of the ‘50s. It’s a Blob of sorts, only the people who made Alien are much more accomplished filmmakers.

Ultimately it is film technology, as much as anything, that makes Alien something more than a routine shock show. Its monster is first a horrifying blob, then a vicious snakelike critter with teeth, and ultimately… oh, why spoil it? But regardless of what shape the monster takes, Alien basically is a standard thriller about a bunch of people trapped in a haunted house (in this case a haunted spaceship) with a monster on the loose. You will spend much of the film guessing where the Alien is hiding, when it will strike, and who in the crew it will kill first — and last. There are some surprises.

There are some disappointments, too. For me, the final shape of the Alien was the least scary of its forms. I also wanted to learn more about the organisation, known as The Company, that apparently is running the world back home away from the spaceship. And on a technical level, I was disappointed that the film didn’t convey the enormous size of its spacecraft very well. Once we’re inside the tug, everything seems cramped.

But Alien is mostly in the business of thrillers, and on that score it did provide more than a few. I looked away from the screen during its most gory scenes. Even more enjoyable, though, was watching the film debut of an actress who should become a major star, Sigourney Weaver (she probably changed her name from Alice) makes an auspicious debut as one of the sturdiest crew members. A number of people who had seen Alien claim that Weaver, in looks and voice, is a dead ringer for Jane Fonda. I don’t share that opinion but clearly, her appeal is that of a strong but seductive woman, and that, I suppose, is Fonda-like.

In sum, Alien is not worth getting oneself into a vomiting dither about, but it is an accomplished piece of scary entertainment.

Heart-pounding terror: Alien

~ by Pete Lewis

The Des Moines Register Sun

June 3rd 1979.Ridley Scott’s science fiction film Alien was released by 20th Century Fox two years to the day after the same studio release the phenomenally successful sci-fi epic Star Wars. The two films share a few production workers, but otherwise are galaxies apart.

Where Star Wars was a light-hearted romp of space fantasy that had its roots in the swashbuckling adventures of yore, Alien is a gory thriller that recalls Jaws, House on Haunted Hill, The Tingler, and nameless dozens of 1950s space monster movies.

Jerry Goldsmith’s excellent soundtrack sets the eerie tone as the movie opens, and if there’s any doubt as to the intent of the film, it is dispelled by the first view of the space tug ‘Nostromo’ (shades of Joseph Conrad) as it tows 200 million tons of ore back to Earth. In the gloom of deep space, the ore refineries resemble the ominous, gothic mansions that have been home to countless terrestrial horror stories. The interior views of the Nostromo lend to the mounting apprehension as the camera snakes though its vast, yet claustrophobic corridors.

The ship’s computer, ‘Mother’, intercepts a patterned broadcast signal that indicates intelligent life, reroutes the Nostromo and awakens the crew that has been in deep space hibernation.

It is our first view of the Nostromo crew: Captain Dallas (Tom Skerritt); warrant officer Ripley (Sigourney Weaver); science officer Ash (Ian Holm); executive officer Kane (John Hurt); navigator Lambert (Veronica Cartwright); Engineer Parker (Yaphet Kotto) and his monosyllabic assistant, Brett (Harry Dean Stanton). And of course, the ubiquitous mascot, Jones the Cat.

It is a refreshing blend of fine actors in brief parts, with especially noteworthy performances from Cartwright and Kotto. Weaver, who brings to mind the young Jane Fonda, is in fine form for her screen debut. Jones the Cat brings to mind the young Morris.

Even Shakespearean veteran Ian Holm manages well despite being shackled with an incredibly asinine character. Why screenwriter Dan O’Bannon included Holm’s character in a script already riddled with holes (black holes?) is one of the mysteries of the universe.

Anyway, whether it’s because their own conversation is so boring, or because they’ve been ordered to do so by a vaguely sinister organisation called ‘The Company’, the crew members are compelled to seek out intelligent life forms. They arrive on a bleak, howling, frozen planetoid and discover two things: the remains of a giant space ship, and director Scott’s obsession with sexual images.

In the womb of the ship they discover the fossilised remains of a giant alien (not the title character, however.) The giant, it soon becomes apparent, is but the first of many victims of the real alien (the title role.)

The message intercepted by Mother, it turns out, was not an S.O.S. but rather a warning sent by the dying giant.

Thus begins Alien. What follows is a terrifying film filled with psychological and jack-in-the-box horrors that will curdle your blood and dialogue and plot twists that will curdle your brain.

Take these examples (please):

“Let’s get out of here,” says Lambert to Dallas. As things get really spooky, she offers, “Let’s get the hell out of here.”

Parker concurs: “This place gives me the creeps,” he mutters.

Dallas catches on: “I just wanna get the hell outa here, awright?” he tells Ridley. Later, he announces, “I want to get the hell out of here.”

Their eagerness to get out of there is attributed to the alien, which assumes many equally repugnant forms, and is, in the words of science office Ash, “one tough [expletive deleted].”

Ash elaborates: “… A perfect organism; its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility… It’s a survivor — no conscience, no remorse, no delusions of morality.”

So, the crackerjack crew that in minutes can whip up sophisticated electronic tracking devices —“It works on micro-changes in air density”—sets out to slay the monster with torches, much as did the 18th century townsfolk in Frankenstein.

Ah well. Despite director Scott’s penchant for ramming the camera lens up under the actors’ noses, the film is beautifully photographed. The suspense is maintained (except for a temporary breakdown when the Ash character short-circuits into absurdity) and is ushered along quite nicely right up to the denouement. And the special effects are very special and very effective.

Weaver does unload one good line (in frustration at the computer ‘Mother’) but otherwise the dialogue is unrelentingly tepid, and in the case of closing lines, downright corny.

But short of screaming ‘BOO!’ probably no dialogue could do anything to enhance the heart-pounding terrors of Alien. The movie is advertised with the slogan, ‘In space no one can hear you scream.’ In the theatre you can hear everybody scream.

Alien is rated R, restricted. It contains considerable violence and gore, and some profanity. Definitely not suited for children.

Alien is frightening; killing gets boring.

By Paul Koval

The Decatur Daily Review

Tuesday June 26th 1979.Alien starts out superbly. Director Ridley Scott manoeuvres his camera through the empty corridors of the commercial spaceship ‘Nostromo’. The camera’s movement is restless as it searches the spaceship for signs of life. We in the audience are vaguely tense, waiting for something to happen.

Right away it is obvious that we are being manipulated by a talented director. Scott knows how to pull the strings of his audience’s emotions. Seemingly at will he can jolt us into shock or keep us breathless in suspense. Oddly enough, this mastery of the audience by Scott turns out to be both the primary strength and crucial weakness of Alien.

The film’s story line is fairly simple. The space vessel ‘Nostromo’ encounters signs of intelligent life. The crew members of the ship are then sent off to investigate.

Through a frightening turn of events, the alien life form they discover manages to get himself aboard ship. Once there, the alien methodically begins killing the crew members.

Exactly why the alien finds it necessary to kill every moving thing in sight is never made clear. The audience simply has to accept this side of his personality without question.

This lack of motivation for the alien’s rampage is symbolic of the manipulative tendencies of the entire movie. Scott wants the people on board to be hunted down, so he invents an outer being to do the dirty work. The monster just as easily could have been the shark from Jaws or the 15-foot mutant in Prophecy.

All Scott is interested in is frightening us. No attempts at thematic development are made. For that matter, there are not even any attempts made to develop the characters beyond cardboard depth.

Probably every member of the cast, excluding screen newcomer Sigourney Weaver, will be recognisable to you by face if not by name. Yet none of these talented actors (including Yaphet Kotto, Tom Sherrit [sic], and Veronica Cartwright) are ever given a chance to do anything. They are all used merely as pawns to be killed off at the director and Alien’s whim.

For the record, Alien did succeed in frequently frightening me. Unfortunately, as time passed the scares decreased with the repetitive violence of the movie. By film’s end I had been subjected to the pointless aggression of the alien for so long I was bored.

And I was also irritated with Ridley Scott for setting his sights for mere thrills when a director of his obvious talent is certainly capable of much more.

Alien attempts to wed genres of science fiction and terror

~ by Joseph Gelmis

The Clarion Ledger Sun

Sunday June 17th 1979.Alien entertains by punishing. Alien looks to be the season’s biggest hit. The implications are disturbing.

There is a mass audience for sick entertainment, and Alien is the slickest of them all and therefore, the most realistically repulsive movie to be offered by a major U.S. company in the thrall of this latest trend.

Set aboard a spaceship a hundred years from now, Alien offers several gruesome episodes. The first —and most harrowing— graphically depicts a man’s stomach exploding. Gore splatters on his fellow crew members. Out pops the alien, on his way through a series of shape changes, getting bigger and uglier and more powerful each time.

Alien is merely an atmospheric monster movie featuring the savage demolition of human and humanoid bodies. It is a movie about five men and two women trapped aboard an interplanetary ship with a remorseless killer—who just happens to have, in his service, a $9 million dollar budget and an army of makeup and special effects workers to make him ferocious.

What distinguishes Alien from another movie in the atrocity trend, Dawn of the Dead, is the money and skill lavished upon it. Dawn of the Dead is lower budget, lower grade shock “entertainment”. (That film highlighted cannibal zombies having their brains blown away by bullets in scores of close-ups.)

The only meaningful difference between the two movies is production values. Each film had its share of outraged and offended viewers who walked out of preview screenings. Each film is, ultimately, an oppressive, calculated nightmare violation of the human body. Each film is, in a word, obscene. But Alien is technically effective moviemaking while Dawn of the Dead is crude on nearly every level.

Money isn’t the only criterion for making a realistically terrifying horror movie. Cut-rate crudity has proved to be a virtue in such shoe-string budget, it’s-so-bad-it-looks-real movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Night of the Living Dead. Thus, money isn’t the only criterion for making a realistic slaughterhouse thriller. The significant thing about Alien is that 20th Century Fox spent about as much on it as on Star Wars and that Alien is not an independent exploitation film but a corporately-funded freak show. Fox is counting heavily on Alien to be its summer blockbuster.

Alien has some value, aside from the purely esthetic use of sounds and images, as a sign of our times. A predominantly young mass audience eagerly endures the most terrible and excruciatingly painful assaults on the human body that the mind of any shockmeister can invent. The era of the simple ‘disaster’ movie has passed. Each advance in screen realism automatically leads to the next. Jaws did not end a cycle. It began one. It is ironic that, unable or unwilling to top themselves in straight terror, the producers of the two Jaws movies plan to collaborate with the National Lampoon people to emphasize sick humour when next the man-eating shark eats.

What makes morbid and sick subjects and treatment so fascinating in our time? Future historians will have to sort out the causes. What we can observe right now is the vicious cycle that produces the films we see. Alien is an attempt to wed the two most successful genres —sci-fi (Star Wars) and terror (Jaws)— of the 70’s. The major companies are caught in a jackpot fever to keep up the conglomerate-mandated annual growth rate. They will exploit a nerve that shows, go as far as the public will allow.

Ridley Scott, the British director of Alien, obviously wanted his film to do one thing: Shake up the audience. Scott had gotten good notices for his first film, The Duellists, based on a Joseph Conrad story, but the movie didn’t do well at the box office. Scott claimed recently that he was not paid for his work on that film, since he deferred his salary and The Duellists didn’t earn a profit.

Scott spent eight years “knocking at the door” to get a film made, supporting himself by shooting TV commercials. “Then I analysed my problem with The Duellists and I realised that I had not entertained,” he said. “When I was offered the script for Alien,” said Scott,” it never occurred to me to question the morality or value of the material. I saw it as a chance to scare an audience.”

Fear is game amoral Alien plays — but it wins.

~ by Jacqi Tully

The Arizona Daily Star

Sunday June 24th 1979.Science fiction and horror join hands in Alien to produce a chilling, calculated, effective and infinitely repulsive cinematic adventure.

It’s a movie without a soul, replete with glittering hardware, several monsters and director Ridley Scott’s supreme indifference toward humankind.

Scott’s given us a new breed of movie, one that combines two highly successful genres with a vast sum of money. That money —$10 million— gives the horror movie unique status. The 1950s spook shows exuded a tackiness that let us achieve distance from the screen image.

But the supreme polish of Alien serves to heighten the fright factor. All Scott wants is to scare the hell out of his audiences. He succeeds. But he also gives new thought to the notion of amorality.

No doubt it’s an innovative, spectacular achievement in the field of special effects and clean, precise execution of visual disgust. But it’s also a predictable plot that begins beautifully and quickly succumbs to a perfunctory series of “who’s gonna be next” killings.

The story is simple: Dan O’Bannon’s screenplay tells of seven astronauts, five men and two women, working on a rather rusty commercial spacecraft deep in the womb of outer space. They encounter a strange, octopus-like creature. It cements itself to the face of one of the astronauts and finally disappears, only to explode through his chest. As the monster grows, so too does the horror.

The rest of the crew desperately tries to confront and kill the creature, which continually changes shape and colour. But this mysterious force only strengthens with battle, systematically terminating the humans.

A curious and rather appealing quality surfaces at the film’s beginning, with the fellow space travellers wear and light hearted. Tom Skerritt, Sigourney Weaver, Veronica Cartwright, Harry Dean Stanton, John Hurt, Ian Holm and Yaphet Kotto want to get home. They’re rumpled and dishevelled and cynically put off when they’re ordered to investigate the strange object.

The eerie, haunting quality that so often gives horror movies an odd sense of grace and style gives Alien an initial lift.

But Scott isn’t interested in building suspense. He wants terror to chart the course of each second of the film. So there’s not a moment of rest, reflection or pause. It’s all exploding guts, severed heads, drooling saliva, slimy innards and cold violence.

As the crew members scream to their deaths, panic intensifies, and in the midst of this domino death game, an odd scene occurs. The scientist on board (Holm) wants to keep the creature alive. But the commander, Ripley, played marvellously by Weaver, is now in charge. Her boss has been killed. She tells Holm they will not save the creature but rather will try to save themselves. He beats her to a pulp, and then we discover that he’s a robot. His head is severed and insides exposed.

It’s a shocking moment to watch because Scott chooses to have his audience watch a woman, and the hero of the film, bloodied unmercifully. And it’s precisely that sort of manipulation and coldness that gives Alien its empty, heartless and amoral tone.

Scott is talented. So, too, are the actors, though they never have a chance to exhibit their deftness. They exist only as objects of elimination. Production designer Michael Seymour and all the special-effects people have produced a superb design for the ship and the monster’s various evolutions.

Alien is supremely sophisticated, then, but it’s a freak show with each gesture calculated to evoke both fear and loathing. So it is meaningless, finally, because once the shock wears off, nothing is left.

Alien will make an enormous sum of money; it has already broken Star Wars’ box-office records for the first two weeks. It will be seen because it is different and because many moviegoers thrill to the chills of monsters and madness.

But it’s an empty film proceeding on repulsion. It glitters with expertise and gloss. Alien isn’t fun, though. Nor is it funny. And it isn’t concerned with substance. Fear’s the game, and Alien will break box-office records on that single, and in this case, shallow emotion.

The thing about critics is that they don’t like or respect genre films.

And their disdain for them naturally results in them not caring enough about them to bother understanding them, and judging them by the expectations of the mainstream “cinema” that they do like but that a genre film isn’t intended to be. Its like asking somebody who only likes apples and doesn’t like oranges to write a review of an orange.

A perfect example being roger ebert.

He’ll confidently write a review about a sci-fi film and announce whether it was good or bad, and ALWAYS gets it wrong. And he’ll explain the reasons how he came to his conclusion, and they’re always all the wrong reasons.

Like the shnook above who was disappointed that the Aliens motivations were not sufficiently explained to him like his favorite Robert Altman relationship drama.

A more welcome early Christmas present I could not imagine- another excellent post, Valaquen.

Almost without exception, these initial reviews have at least three parallel similarities-

1- An unconcealed and grudging respect for the fully-realised setting and arresting visuals.

2- A total misreading of one of the film’s greatest strengths- the subtle characterisations, the hyper-real acting and cunningly underplayed script. As time elapsed and the discombobulation of the visuals became instead, a marvel of future-realistic beauty and implied function, repeat viewings increasingly focused on and revealed the excellence of the performances.

3- The technical excellence of the reviews themselves. With beautiful command of language throughout, the reviews all have the weary, cynical and icy gaze of…Alien itself.

Great to read another super instalment. Hope you and yours are doing great.

A couple of excerpts of note-

Gene Siskel- Possibly the most pertinent and perceptive of all the observations of Alien on its release- that ordinary people’s lives would not fundamentally be much different than today. All the technology, all the material advancements will make no difference to people’s happiness, fulfilment or prospects. This cautionary tale in the subtext was Alien’s real gift to us all.

Dick Shippy- Three words. Rikki. Tikki. Tavi. Never, before or since, has Jones’ self-serving antics and dismal lack of heroics been skewered so effectively. And with such brevity! A six syllable Kipling literary reference says it all and opens a nice little door to discover a quite excellent story.

Link to a very beautiful Soviet animation from 1965, subtitled-

And some love for Morris, the 9Lives kitty who could be an ancestor to Jones 😛

Dear Morris, another fussy, fickle feline. But no Rikki Tikki Tavi.

Happy New Year to you and yours Valaquen.

It’s always funny to look back and see when contemporary critics got a film wrong. But then, culture is a funny thing. It’s hard to tell what films will land and what films won’t.

Pingback: Alien Reviews From Yesteryear | Strange Shapes. – The Nostromo Files