In the closing moments of Prometheus Shaw and David, having struck an uneasy alliance, dart for the Engineer homeworld and leave LV-223 behind them. “There is nothing here but death,” Shaw narrates. But in the wreckage of Vickers’ escape pod the Engineer suddenly shudders to life – his chest cleaves open and a new life-form emerges: a spindly-limbed creature known as the Deacon, or, as the early script by Jon Spaihts call him, the Ultramorph.

“I wrote five different drafts of the script,” explained Spaihts, “working with Ridley very closely over about nine months. And even as we were working, we were constantly toying with the closeness of the monsters in the film to the original Xenomorph. You can see an interesting balance, even looking at the movies in the Alien franchise, between homage and evolution. In every film you’ll see that the design of the Alien shifts -the shape of the carapace, the shape of the body- and some of that is to do with new technology available to realise the monsters, but a lot of is just a director’s desire to do something new.”

“And so he was always pushing for some way in which that Alien biology could have evolved,” he continued. “We tried different paths in that way. We imagined that there might be eight different variations on the Xenomorphs – eight different kinds of Alien eggs you might stumble across, eight kinds of slightly different Xenomorph creatures that could hatch from them. And maybe even a rapid process of evolution, still ongoing, in these Alien laboratories where these Xenomorphs were developed. So Ridley and I were looking for ways to make the Xenomorphs new.”

One of the new Alien variants would be the Engineer-Alien; the creature that presumably erupted from the chest of the Space Jockey in Alien.

Alien insects: Again, just as they did on Alien, Ridley and the creative team turned to the brutal insect world for inspiration. Spaihts told Empire magazine: “Ridley is a great and ghoulish collector of horrible natural oddities, real parasites and predators from the natural world. He had a tremendous file of photography of real, ghastly creatures from around the world – they’re chilling, some of them! He would tell these tales with relish, of wasps that would drill into the backs of beetles and plant larvae, or become mind-control creatures. Terrible things happen, especially the smaller you get. As you get into the insect world or the microbial world, savage atrocities are perpetrated by one creature on another. And Ridley was thrilled with all of them. They inspired a lot of the designs and a lot of the ideas we tried.”

An Alien born from a Space Jockey is an angle already explored in the series’ expanded universe. One appeared in the comic book Aliens: Apocalypse – The Destroying Angels, and another in the Nintendo DS game Aliens: Infestation – both designs bore no similarity to one another, the Jockey-Alien being an unseen element in the films. Artists were free to render it as they wished. The hypothetical creature has also been the subject of fanart over the last few years. Spaihts’ Alien: Engineers movie would have been the first in the movie canon to depict the monster.

Alien: Engineers, as Spaihts’ script was called, would also expand Ridley’s notion that the Alien was a weapon of war and not a naturally occurring creature in its own right. The Alien had long been theorised to be an unnatural creation. In addition to Ridley’s ideas about the origin and purpose of the Alien, James Cameron also considered the theory that the Jockey may have been on a mission of either peace or war: “Perhaps he was a volunteer or a draftee on the hazardous mission of bio-isolating these organisms,” he said in an issue of Starlog magazine, before also postulating: “Perhaps he was a military pilot, delivering the Alien eggs as a bio-weapon in some ancient interstellar war humans know nothing of, and got infected inadvertently.”

The idea was explored in almost every one of Alien 3′s many scripts, which saw the Company’s weapons division attempting to domesticate an Alien for their own purposes. In David Twohy’s Alien III the antagonist Dr. Lone recognises their lethal potential: “Company assets are, as you know, many and far-reaching,” he says, justifying his use of Aliens as weapons, “There will always be a need for defensive weapons.” In Eric Red’s Alien III, Dr. Rand comes to the same conclusion: “This organism, on a cellular, even a molecular level, is purely and totally predatory. We have never encountered an organism that had its characteristics… or its potential.” Dr. Rand goes on to confidently declare to an audience that she has tamed the Alien for future military applications. She approaches the creature and…

“The Alien’s first set of jaws open, piledriver jaws jackhammering the back of Dr. Rand’s head, exploding it off her shoulders in a shower of meat. Her decapitated, spurting body collapses to the floor.”

… its obedience was feigned. The Aliens likewise pretend to be obedient in an issue of the early Dark Horse comics – when the moment is right, they unerringly strike, to the shock of their would-be masters. The Alien seems to be a fantastic weapon, save for one element: control. Alien Resurrection and many of the expanded universe stories explored not only the Aliens’ tenacity and single-minded will, but also their intelligence and ability to quietly strategise amongst themselves when under duress.

Lack of control is a long running theme of the series (first hinted at in the first movie: the Space Jockey is clearly shown to have fallen victim to his cargo) and even containment is an arduous task. Ash is more content to allow the Alien to run amok; analysing and admiring the creature’s lethality seems to be his kick. Though he sabotages any attempt to expel or harm the Alien, he likewise makes no move to contain or communicate with it – he may have deduced that it may not be possible to do so. In Alien 3 the Company’s intention to capture the Alien is dismissed by Ripley as being futile and self-destructive. “They can’t control it, they don’t understand it, it will kill them all.” She would know. After all, her plan to trap the Alien only briefly succeeded.

In Spaihts’ screenplay the Engineer facility on LV-426 (LV-223 after Lindelof’s rewrite) is a testament to the Alien’s unsuppressible nature. The creatures there, some time ago, managed to infect and annihilate their creators. One Engineer (called the “Sleeper”) manages to stow himself away in cryosleep, and is found eons later by the protagonists of the story, who rouse him from his rest. The Engineer attacks the humans and launches his ship, the Juggernaut, but succumbs to the Alien’s birth pangs:

“In the pilot chair, the Sleeper convulses. An ALIEN erupts from his chest. Big as a wolf even at its birth. Dark grey, armoured, lethal. More hideous than any chestburster we’ve seen. An ULTRAMORPH. It wails hideously. The Sleeper dies. The Alien slithers free.”

~ Alien: Engineers, by Jon Spaihts.

Janek and Shaw take advantage of the Juggernaut’s loss of control and ram their own ship into it. Both ships subsequently crash and the Ultramorph rises from the wreckage and stalks Shaw, who eventually kills it with a diamond-tipped saw.

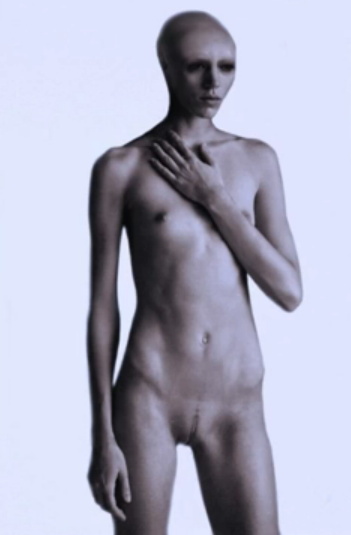

But the Ultramorph was not the only Alien to feature in the original script. Different variations cropped up throughout the story, including an alabaster, dolphin-headed Xenomorph that is born from Holloway. The classical Giger Alien is pulled form Shaw’s body during the MedPod scene, and she quickly dispatches it once the creature reaches maturation – “I brought it in,” Shaw tells Captain Janek, hefting her gun, “I took it out.”

The Holloway Alien however is given some time to rampage through the ship, and kills many of the crew.

“It is a humanoid demon, spindly limbs and bony back. Boneless and flexible and monstrously strong. A threshing eel’s tail. Its blunt head dolphin-like and elongated … A nightmare image, a translucent white goblin. Backlit, it shows the strange shape of a human face inside its fleshy skull. A mockery of Holloway.

And then it’s gone.”

~ Alien: Engineers, by Jon Spaihts.

This particular Alien is able to sift through vents and small spaces, and its carapace only barely masks a leering human skull – just like the original Alien from the 1979 movie. Spaihts talked to Empire about the Holloway Alien’s appearance: “We toyed with the notion that the Xenomorphs might have a soft carapace like a soft-shelled crab, and be flexible and able to squeeze through cracks; that they might be pale rather than black; that they might retain inside some gelatinous cowl some resemblance of the human being in whom they’d incubated. We played with a lot of ghoulish notions like that.”

When the script was rewritten by Damon Lindelof (as a script titled Paradise) these Alien creatures were cut and replaced by other monsters. The Ultramorph, retooled as the Deacon, was saved for the closing scenes, but it never encounters any of the film’s human characters. Where it goes after its birth is not known, its intelligence and motives can only be guessed at, and some called its inclusion an unnecessary and overly obvious tip of the hat to the Alien series, from which Prometheus had previously seemed desperate to divorce itself.

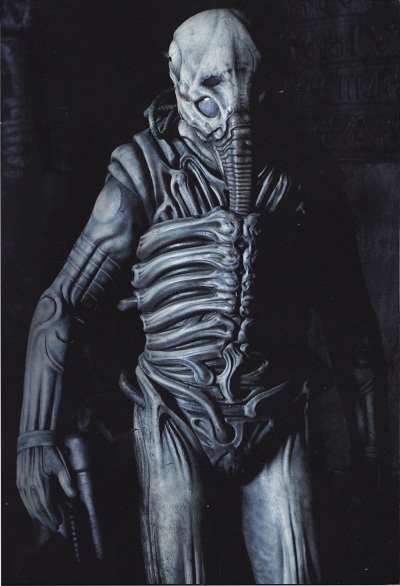

The design of the Deacon primarily fell to conceptual artist Carlos Huante, who was keen to explore Giger-esque forms and shapes. Many of his initial designs mimic early Alien concept pieces, but Ridley, as he did with other conceptual artist Neville Page, steered Huante away from mimicking Giger’s style, though Huante found the influence irrepressible. “The genesis of that character came after a conversation I had with Ridley about a design progression of the creatures to the Xenomorph of the first film,” he told AVPGalaxy. “I went home and thought about it, but kept on with the Giger-esque Ultramorphs.”

Once I realized that this film’s timeline was taking place before the Giger-esque aesthetic would come into effect, I started homing in on a design aesthetic [that] I felt would complement the beautiful Giger style that saturated the first film. I wanted everything white and embryonic. Ridley and I were right in tune with each other on this. I mean, Ridley was looking at paintings that had white ghost-like creatures, as reference for the Engineers. I loved the idea of pale white and started developing that as an overall concept for all the creatures.”

~ Carlos Huante, Prometheus: The Art of the Film, 2012.

“Then as I worked I thought, ‘wouldn’t it be cool if these Aliens, who are born of humans and haven’t been mixed genetically with the Engineers yet, would look more human and less biomechanical?’ Of course this was for a different version of the script, but that’s where the Deacon (or Bishop, as he was originally named) came from. He later became an Ultramorph and as the script changed slightly after I left the show, it became that thing at the end.”

The original concept of the Deacon looked similar to the Holloway-Alien in that it was tall, pale, and its head ended in a point.

The Deacon became a shade of blue in other pieces. Huante explained that blue tone was used to emphasise its whiteness in varying shades of darkness. Its skin also had a translucent quality…

As the design went through different permutations Ridley decided to move away from the ‘Ultramorph’ name for something else. At first it was referred to as ‘Bishop’, but this became ‘Deacon’ for obvious reasons. “It looks like a bishop’s mitre, the evil deacon’s pointed hat,” explained Arthur Max.

The Deacon in the film is not as magisterial as the concept art, which depicted a fully-grown Alien rising from the caracss of the Engineer. The film opts to show the Deacon as a vulnerable creature that rises but tumbles as it is born: it is connected to its host via an umbilical cord and is sustained by an egg sac for feeding upon.

“Foals are gangly and ungraceful,” explained Neil Scanlan, “but have to grow quickly. A foal or a giraffe, if they’re born in the wild, out in the open, have to get on their own feet and get ambulatory very quickly. They’re ungainly, but they develop fast, and that’s what we wanted, so that was the strategy with the Deacon.”

As for its skin tone, Scanlan said: “The quality of the Deacon’s skin is based on the placenta when a horse gives birth. Steve [Messing] managed to get it — something between horrific and beautiful with the way he rendered the quality of the surface treatment. It had a sort of iridescent quality we really wanted. So it was kind of beautiful-scary.”

But Carlos Huante was not impressed by the Deacon’s dark blue skin and design changes from picture to film. “Why it was blue?” he said to AVPGalaxy. “I don’t know… The illustration was blue so as to emphasize its whiteness in a dark blue setting, and I was following some inspirational paintings that a contemporary Russian painter did of a man’s head that Arthur [Max] had sent me from Ridley. The creatures were all supposed to be albino. They were supposed to look simple, beautiful and ghostly, like a Beluga whale in dark Arctic water.”

“I wish I could have stayed on to supervise the follow-through with the designs,” he explained further. “My biggest disappointment is that what I did got modified, of course. Any artist would say that. But I really thought they were going to make my Deacon, but for some really strange reason they went with the one from the storyboards which was not my character and not the design.”

Huante reckoned that the production took note from the film’s storyboards rather than his concept art. “The board artist illustrated it for the purposes of storytelling for the storyboards but not as the design,” he said. “The design of the actual Deacon was abandoned … I’m shaking my head as I write this.”

When they met in London in early 2011 Ridley toured Giger around the film’s production offices, showing him the concept art of the various creatures. Giger, sitting at a desk with Scott, sketched some tentative alterations that ultimately were not integrated into the final designs.

THE ENGINEER lies on the ground, STILL.

Next to it, the TROGLYBYTE. Equally motionless looking very much like a DEAD OCTOPUS. And then…THE ENGINEER’S BODY STARTS TO TWITCH.

His ABDOMEN slowly rises — SOMETHING IS MOVING — UNDULATING BENEATH HIS SKIN LIKE A MASSIVE PYTHON — PRESSING AGAINST IT. AGAIN. AND AGAIN. AND — BURSTS OUT OF THE ENGINEER’S CHEST. A CRYSTALLINE PLACENTAL SAC FLOPS ONTO THE GROUND WITH A SICKENING SPLASH OF VISCOUS FLUID

— And now —

A RAZOR SHARP POINT PUNCTURES THE SACK FROM WITHIN — SOAKING THE CARPET WITH GOOP as it TEARS OPEN and in MAGNIFICENT GLORIOUS FASHION —

AN OOZING, ASTONISHING CREATURE — A DEACON — SLITHERS TO THE GROUND LIKE A HORRIFIC TUNA. FIERCE. TERRIFYING.

And it rises to it’s full TERRIFYING HEIGHT. Takes its FIRST STEPS towards the OPENING at the end of the room.EXT. PLANET, CRASH SITE, VICKERS’ MODULE – DAY

Stands there now — SURVEYING THE PLANET with the cold, detached air of a HUNTER.

~ Paradise, by Damon Lindelof.

The reaction to the Deacon was mixed. It hasn’t gained any of the stature of Aliens from the previous movies, though many fans are optimistic to see the creature as an adult. Its appearance in Prometheus can be compared to that of the newly-born dog Alien in the third movie – both creatures had yet to shed and mature into adults.

Some fans also humorously pointed out that the Deacon bore an unfortunate resemblance to monsters from other films, most notably the alien monster from the comedic Alien vs. Ninja: