May 1978, and production, with all its attendant problems, was well underway at Shepperton Studios.

Though sets were being mapped out and constructed, some were being hotly debated; the Alien had been committed to canvas, if not rubber (Giger had not, for now, been tasked with the actual construction of his monster); the script was in a constant state of flux, and tensions between the producers and the film’s writers were beginning to break out with Ridley, trying to compromise between the O’Bannon script and the Giler/Hill rewrites, being stuck in the middle of a writers feud that had opened, and would probably close, the film’s inception and completion.

There was another, arguably more pertinent problem: in a month the cameras would finally roll, but the part of Ripley had yet to be cast. Auditions for the part had seemingly wrung Los Angeles and New York dry. British-American actress Veronica Cartwright had read for the role twice, and Ridley reckoned that he wanted her for the film, but her ability to convey catatonia and fear—a talent that Scott and casting director Mary Goldberg especially admired— wasn’t a fit for Ripley. “Laddie was going crazy,” Ridley remembered, “saying, ‘You’ve gotta make your mind up.’ I said, ‘Yeah, you know, I can’t find it yet.’”[1]

Several other actresses had been prospected. Twentieth Century Fox had initially pushed for an established actress to give the film heft: Katherine Ross or Genevieve Bujold, but stars of that calibre were not keen to be involved with a grubby science fiction movie. The success of Star Wars however convinced Fox that unknown actors could carry a successful film if buttressed by an established face or two, as Alec Guinness and Peter Cushing had done for Lucas’ unfamiliar cast.

One better known star who read for Alien was English actress Helen Mirren, who admired the refreshing ambiguity of the characters’ sexes. “I read the original script for that,” she said, “and when you read it, you had no idea which character was male and which was female. They were just people engaging with each other in this situation. They all had these sort of asexual names, so when Ripley said or did things, you had no idea whether Ripley was a man or a woman. You could have interchanged all the characters —they could have been all male or all female— any one of them could have been anything.”[2]

“There was no, ‘a lean 32 year old woman who doesn’t realise how attractive she is’ – there was absolutely none of that!” Mirren continued. “You had no idea who was a man and who was a woman. That was the revelation.”[3]

It wasn’t until the USA casting department put forth two choices for the role that the production started encircling potential Ripleys. The first suggestion was Meryl Streep, an up-and-coming theatre actress who briefly appeared in Julia (1977) and had recently wrapped on Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978) with her partner John Cazale. Unfortunately, Cazale, in the end stages of lung cancer throughout The Deer Hunter’s shoot, died March 12, 1978, and Gordon Carroll did not think it appropriate to ask Streep to consider the role.

“The other woman,” Carroll remembered, “was of course, Sigourney Weaver.”[4]

Susan ‘Sigourney’ Weaver was, of a sort, American aristocracy. Her grandfather Sylvester Laflin Weaver left St. Louis for Los Angeles in 1893 and placed an ad in the Times to find work, with salary “no object”. For years he eked his way as a janitor, book-keeper, shipping clerk and salesman. “I finally became sales manager,” he explained, “making stops at San Luis Obispo, El Paso and the City of Mexico, during which I accumulated a wife, four children and a fair modicum of this world’s goods.”[5] In 1905 he was chairman of the Chamber of Commerce, overseeing the development of Los Angeles Harbour, and in 1910 founded his own roofing company, Weaver Roofing; it was said that most, if not all, of L.A.’s emerging suburbs at the time had been roofed by Weaver.

His ambitions did not end there: he was president of the Los Angeles Rotary Club and then, in 1917, was elected a director of the L.A. Chamber of Commerce. In 1919, Weaver, now a beloved and influential figure, ran for Mayor. His candidacy was received with enthusiasm: he was the centrepiece of a parade that rolled down Broadway “while bands played, horns blared, guns popped, red-fire flared and flashlights streamed their beams.”[6] But his mayoral candidature was not to be; he came in third place.

Yet this disappointment, coupled with the 1921 destruction of his roofing plant by fire, dampened neither his fortunes nor popularity. The family’s frequent partying and holidaying was a regular subject of the local papers and gossip circles. His wife wrote operas, books and was a patroness for charitable events. His four children —two sons, two daughters— lived accordingly. “My father was one of the young men about town,” remembered Sigourney. “He used to go out with Loretta Young and her sisters, and he went to high school with Carole Lombard, whose name was Jane Peters then. He used to date all the stars.”[7]

Sylvester ‘Pat’ Weaver Jnr, like his father, was never still. Starting out as a writer for KHJ radio, he quickly became program manager, switched to managerial positions in advertising, served in WWII, and then joined NBC in ’49. By ’53, he had been vice president of television and radio, then vice chairman of the board, and finally president of NBC. In ’43 he married English actress Elizabeth Inglis, who had appeared in Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (1935) and opposite Bette Davis in The Letter (1940), with their children Trajan and Susan Weaver coming along after the war.

By the time Susan Weaver was born in 1949, the Weaver family was still firmly on the ascendancy. Her uncle Winstead ‘Doodles’ Weaver was a celebrated television and film comedian, “Manhattan’s favourite clown”[8] according to the press; her aunt a noted New York Times fashion critic, and her father the president of NBC, where he heralded both Today and The Tonight Show. “I was brought up in a show business environment,” she said. “Actors and famous people were there when I was a kid. The unusual was usual for me.”[9] She remembered stars like Art Linkletter visiting her father at their home on Long Island, and being “miserable because I was quarantined with the chicken pox.”[10]

Sylvester ‘Pat’ Weaver with his daughter Susan Weaver. June 1955.

It was at the Ethel Walker School for girls in Connecticut where Susan adopted the name ‘Sigourney’, lifting it from a one-off character in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. The name, she thought, would stop her classmates from calling her ‘Weaver’, and she was from a family of odd names anyway. Her father once suggested naming her Flavia —his interests, obviously, firmly Roman— but her mother relented, choosing instead to name their daughter after family friend Susan Pretzlik. “A very interesting woman,” said Sigourney. “She was quite an explorer. And if I had met Susan before I switched over to Sigourney when I was 13, I probably would have kept it.”[11] But, for the adolescent Weaver at the time, “To be named Susan in a family like that seemed inappropriate.”[12]

Her family took to Sigourney easily enough. “They called me ‘S’ for a while in case I changed it to something else. And then actually they wanted me to keep the Roman part of my name, which was Alexandra—Susan Alexandra Weaver—so my father and I tried to think of a way of calling me Alexandra.”[13]

But her father quickly abandoned this when his daughter’s headmistress pulled them up about the change in name. “Do you permit your daughter to use that ridiculous name?” Weaver remembered her headmistresses asking her parents.

“And my father said, ‘Are you talking about our daughter, Sigourney?’ I thought that was wonderful of him.”[14]

At school she played a greaser in an update of Alfred Noyes’ poem ‘The Highwayman’, and found she had a taste for performance. “I flipped my hair back and wore a big leather jacket and some girls chased me out. I guess I did a good job as an Elvis Presley type.”[15] Tall for her age, gangly and a little awkward, Sigourney discovered that acting could be liberating. “I figured it was like being an explorer. There were so many interesting things to be —a lawyer, a doctor, a biophysicist— and only one life. Acting was a way to get around it.”[16]

Sigourney Weaver at 13.

Her budding acting career was off to a bad start when, while rehearsing for a play at the Red Barn Playhouse, she was quickly replaced when the producer realised her romantic interest was only half her height. She had been a lanky 5’10 at 13, and even now many of her peers had yet to catch up. She stuck out. She looked odd. “I called my parents and described this situation to my mother and she said, ‘Well, welcome to the business.’ She said, ‘Your heart will be broken a hundred times.’”[17]

She found some acting work in weekend productions and summer stock, and even toured San Francisco with a comedy troupe, but these, she felt, were relegations: she wanted to do more, could do more, but no one else was willing to look beyond her height. “I was very much a loner,” she said, “and a self-conscious loner at that.”[18]

It was after gaining her English degree and while preparing for a PhD at Stanford that she decided to tackle acting head on, despite any misgivings about her physicality. Academia, she decided, wasn’t for her. “The course started getting really boring. Finally, I went to my adviser and said, ‘This is a desert, this part of it, right here in the middle. I hope it’s not going to be like this for three years.’ He said, ‘It’s going to be quite like this.’ I said, ‘I don’t think I can stand it.’ I was studying criticism of criticism. It was all this twice-removed stuff—deadly dry. So I just applied to Yale Drama School and got in.”[19]

Her family, who had so often occupied show business echelons, always warned her that the business was unfair, rarely a meritocracy, and even cruel—but she did not expect the disillusion to set in before she had even graduated from drama school. “My acceptance to Yale was addressed to Mr. Sigourney Weaver, so I really wasn’t sure when I got there what they thought they’d taken. My second day there I got violently ill from food poisoning and had to go to the hospital. I’d eaten liver at the Elm City Diner—I was trying to be healthy by eating liver. I remember sitting next to this window on Chapel Street that had a big bullet hole in it. I should have known then….”[20]

At Yale she was rarely cast. Her tutors asserted that she had no future as an actress. The best roles, she remembered, went to classmate Meryl Streep. “I still think they probably had this Platonic ideal of a leading lady that I have never been able to live up to,” Sigourney reflected. “And would never want to.”[21]

If she reckoned that, after graduation, her father’s show business contacts would give her a lift she was to find that she had to rely solely on herself. “When I got out of Yale Drama School I called up a friend of my father to see if he could find me some stage work. He said: ‘Look kid, why don’t you get a job at Bloomingdales?’ Ever since then I’ve been on my own.”[22]

She teamed up with Yale friend Chris Durang, a budding playwright who had been one of the few at Yale to cast her in his productions. “I sensed that the audience had a special rapport with Sigourney,” Durang recalled. “Actors need skill and intelligence—which Sigourney has in abundance—but stars need charisma, which hard work can’t give you.”[23] Sigourney, he knew, had charisma in spades; she just needed exposure. He remembered how, after graduating, casting agents tended to complain about her height and “kept trying to type her as a patrician girlfriend who poured cocktails and nodded politely while the leading man talked.”[24] Stepping in, Durang teamed up with Weaver, casting her in his off-Broadway plays ‘Titanic’, ‘Beyond Therapy’, and ‘Das Lusitania Songspiel’.

Weaver and Durang on a poster for Das Lusitania Songspiel’s 1980 revival.

For Weaver, her adventures off-Broadway with Durang were more than affirming favours from a good friend: they were a life line. “After I left Yale,” said Sigourney, “we were all doing these mad plays off-off Broadway. And I got back to that feeling I had from college, of everyone making up in front of one cracked mirror, which is what I loved—the scrappy theatre idea. I think off-off Broadway healed me, made me an actor again, and I was in so many different crazy shows. I played a woman who kept a hedgehog in her vagina in one play; I was schizophrenic in another. It was just so much fun.”[25]

It was at this time that her name had started to circle around, and she came to the attention of the desperate Alien production. “She came recommended the long way around,” said Ridley, “where somebody had said to somebody, ‘There’s this girl who’s doing theatre on Broadway who’s very interesting, is a giant, I think she’s 6’1 in her stockinged feet. She’s very interesting. Smart performer, very physical.”[26]

To get an idea of how she came across on film, Walter Hill screened Madman (1978), an independent Israeli film that featured Weaver opposite Michael Beck. Liking both actors, he tapped Weaver for Alien, and Beck for his forthcoming film The Warriors (1979). Sigourney was sent the Alien script and invited to audition in New York before Ridley Scott, David Giler and Gordon Carroll.

She did not, at the time, prioritise film roles, having turned down the part of Dorrie in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) when her commitments to Chris Durang’s ‘Das Lusitania Songspiel’ clashed with the filming schedule – Christine Jones took the Dorrie role, though Weaver was afforded a non-speaking cameo in the closing moments of the film as Allen’s date as recompense. It had been the theatre that reinvigorated her, and that was where her loyalties lay; there, she had rediscovered a joy in performing that she thought had been irreparably lost at acting school. When the Alien script came through she was busying herself with the play The Conquering Event as well as various acting and charitable seminars, and didn’t see herself as a science-fiction actor, let alone lead.

“I was doing a seminar called the Hunger Project,” she said, “which was simply about making a difference in the world. Within the context of that seminar a movie part was so unimportant. I went up for Alien and didn’t want to be bothered, because I thought I had not suffered through the Yale School of Drama to do a science-fiction movie. I read the script and didn’t really care that much for it.”[27]

Though she was averse to science-fiction and couldn’t imagine the Alien looking anything other than silly, she still admired how “They had broken the rule and written two of the parts, originally designed for men, for women to play.”[28] One of those parts intrigued her in particular. “Actually, the part I wanted was Lambert. In the first script I read, she just cracked jokes the whole time. What was wonderful about it was that here was a woman who was wise-assing, telling stupid jokes just when everyone was getting hysterical. And she didn’t crack up until the end. That’s a character I could identify with because that’s how I assume I would act. If the elevator gets stuck that’s what I do.”[29]

The audition, held at the Loews Regency hotel on Park Avenue, was almost botched from the start, with Weaver turning up to the wrong hotel. She called her agent and suggested blowing it off, but he recommended that she go ahead anyway. Without much else to do, she rushed for the Regency. Ridley, Giler, Carroll and casting director Mary Goldberg waited, and waited, until finally, thirty moments after she had been due, Weaver turned up. “And then we hear,” said Carroll, “l can’t say running feet in the corridor, but we hear fast-paced feet coming toward the door, and then slowing down, composing itself… The bell rings, Mary opens the door, and Ripley was standing there.”

Weaver was quite the sight – standing over six feet tall in long boots, the panel found themselves looking up at what Carroll called “This extraordinary-looking woman; tall, commanding presence.”[30]

They talked about the script, beginning by asking Weaver what she thought of it.

“It’s a very bleak picture where people don’t relate to each other at all,”[31] she answered.

Mary Goldberg signalled that Weaver was sabotaging her own audition, but Weaver was undeterred from speaking her mind. “I happen to have worked on many new plays with new playwrights,” she said, “so I have been encouraged to speak up — I didn’t know if people in movies were used to that.”[32]

To her surprise (and relief), her interviewers acknowledged the shallowness of the characters, explaining that they were relying on interesting actors to bring them to life. “I thought it was best to put all my cards on the table,” said Sigourney, “because if they really wanted a ‘Charlie’s Angel’ I knew it wouldn’t be right for me. But they were the first to admit that it was going to take a lot of development and close working together.”[33]

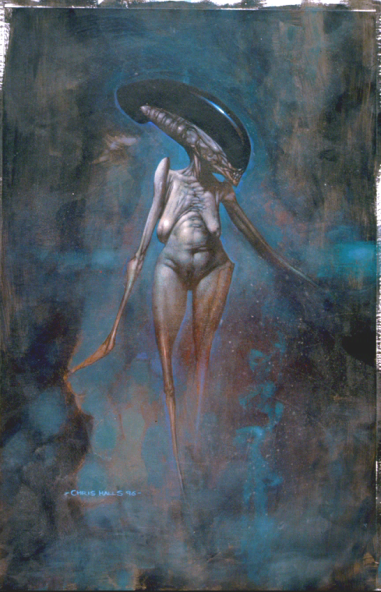

Then Ridley, remembering how effective Giger’s Necronomicon had been on himself, propped up a display of images by Giger and Rambaldi. Weaver was suddenly piqued. This would be the monster. She had never seen anything like it. They broke for lunch, with Scott and the producers taking Weaver for Japanese food on Fifty Fifth Street, where they met Walter Hill, before returning to the Regency to read through the script.

She did not know it yet, but Carroll, Scott and Giler all felt that she was perfect for Ripley the moment they laid eyes on her. “Somehow,” said Ridley, “I knew this was her.”[34] Hill was similarly enthused, but Weaver herself did not feel like a shoo-in. In fact, she was somewhat mystified by the attention. “I didn’t really know what was expected of me as I’d only made one film,” she said, “and an eight-part television series about aristocratic women called The Best of Families.”[35]

But it was her naivety and inexperience that the producers and Ridley knew would be perfect for Ripley. The character was thinly-sketched in the script, the only real characterful moments being her adamancy that quarantine rules be stringently obeyed, and her swift assumption of command after the death of Dallas. Looking at Weaver— her intelligence, twinkling humour and soft-spoken assertiveness as obvious as her strong jaw, high cheekbones and broad shoulders— they could see the blanks being filled already.

Scott had been enamoured the moment she stepped through the door, and continued to marvel at her throughout the day. “Jesus Christ, I was always looking up at her!” he remembered. “I walked into a restaurant with her and she held my hand. I felt like, ‘Mummy, Daddy!’”[36]

“She clearly has the authority that she needs to have,” he continued, “and can give any guy as good as he can give back.” Gordon saw how Weaver could project composure, and yet, “You knew that just an eighth of an inch behind that composure was a very nervous actress, a very tense actress, and that was exactly right.”[37] Giler noted her “American aristocratic” bearing, how she embodied perfectly the officer class.

With the producers and director keen, Weaver was flown out to Hollywood to meet Alan Ladd Jr., and Gareth Wiggin. “I lost my bags on the plane and went in my rotten clothes,” Sigourney recalled. “We had a typical chatty Hollywood meeting where you’re all supposed to pretend you’re there for social reasons and no one mentions the film.”[38]

Ladd, ever cautious, agreed to hire Weaver provided that she complete a screen test first. Scott protested that he was mere weeks from filming, but acquiesced: Fox placed a lot of trust in him due to his self-made success with RSA, but there were still plenty of executives, like Peter Beale, who still viewed him as untested. It irritated Scott, who had left a promising career at the BBC in favour of his independence, to suddenly have his creative decisions become the purview of a committee… but he trusted and respected Ladd, who had allowed head scratchers like Star Wars and Alien to be made at all.

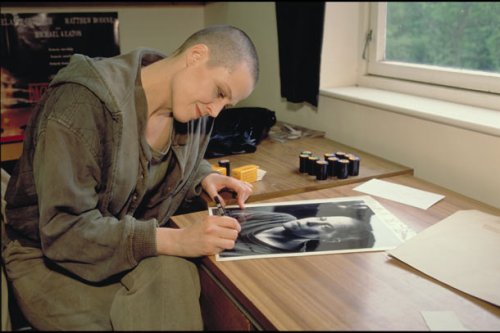

“So,” said Sigourney, “the next week I flew to London. I hadn’t yet been hired but I was the only actress they were screentesting. They hoped I would do well. And we did a run-through of the entire script.”[39]

Weaver filmed her screentest on May 12th. She was apprehensive, imagining that she would have to duck and weave in an empty space or react to a potted plant, but when she arrived she found that Ridley had constructed a piece of set especially for her test. “This test corridor we built was the first look at the interior of the corridors of the Nostromo,” revealed art director Roger Christian. “It established the look of Alien for the very first time.”[40] In effect, not only was Sigourney being tested, but Ridley’s vision for the film was about to be captured—and scrutinised—for the first time.

Ladd watched the test in silence and, once done, picked up a nearby phone. He asked that some of the women upstairs come down to view the rushes with him. “So we ran the test again,” said Ridley, “and Laddy simply then said, ‘What did you think?’ and there were, I don’t know, maybe eight, twelve women who immediately jumped in. One said, ‘I think she’s like Jane Fonda.’”[41]

“Alan Ladd watched the screen test,” explained David Giler, “and had all the secretaries in the building come down and watch it. And they got into a big argument that she looked more like Jane Fonda or Faye Dunaway, and he just said, ‘You can have her. She’s in.’”[42]

Weaver, already on her way home to New York, was not entirely confident. She reckoned she had played her scenes wrong, that she had been too stereotypically tough. “If I hadn’t been in an unambitious place philosophically, I think I would have tried harder,” she said. “In fact, it wasn’t until the day before the screen test that I sat down and thought, well, Sigourney, you’d really better make up your mind if you want to do this or not. They’ve already flown you out here. If you don’t, you’d better think about ending it. I finally decided I really liked the character of Ripley as well as the designs and Ridley Scott. Besides, I didn’t want anyone else to do it.”[43]

Luckily, she was to find that, barely home after her long plane flight, that she had gotten the part. “I had sort of written it off every step of the way.”[44]

But there was a snag when the actors convened for wardrobe fitting. Veronica Cartwright, who was eventually cast in the film after auditioning for Ripley three times, had assumed, naturally, that that was the role she was to play in the film. “I get a call,” she remembered, “and they said, ‘Okay, you need to come in for your wardrobe for Lambert’. I said, ‘Oh no, I’m not playing Lambert, I’m playing Ripley.’ ‘No no… you’re Lambert.’”[45]

“I called my agent back in LA and said, ‘Aren’t I doing Ripley?’ And he said, ‘Yes, I think so.’ I mean, that’s what he thought too. I even auditioned again when I was in England, and the part that I read for was Ripley. They didn’t bother to tell me. And I’d never even looked at the script from the point of view of Lambert. So I had to re-read the script.”

“I heard [about] that,” remarked David Giler. “Ridley had met Veronica on his own somehow and he really wanted her and we said fine, you know. Very good actress. So she was certainly fine with us.”

For her part, Cartwright suspected that internal politics played a part in the confusion. “There was a lot of politics going on during the making of that movie,” she remembered. “It was Sigourney’s first job. But her dad was a bigwig. There were a lot of favours going on. It just got a bit bigger than anybody had planned. And studio pressure and egos and everything got involved.”[46]

There might be some basis for Cartwright’s suggestion, with Alien 3 actor Ralph Brown detailing a 1991 meeting between himself and Walter Hill to discuss rewrites concerning Brown’s character Aaron ‘85’: “I am now paranoid about being cut from the film” he said, “like Veronica Cartwright was from Alien as Walter gently reminded me earlier – ‘I don’t want to alarm you Ralph but, well, yes, actually I DO want to alarm you. Don’t end up like Veronica Cartwright.’”[47]

However, it’s also likely Hill may be referring to the abundance of deleted scenes, many of which, Cartwright had complained after the film’s release, overwhelmingly featured her character Lambert.

Sigourney on the Nostromo bridge with her father Sylvester ‘Pat’ Weaver and mother Elizabeth Weaver.

Sigourney understood that her background would prejudice some against her, especially in an industry that was rife with competitive and suspicious attitudes. “When you are the lead in a film that costs a few million dollars,” she said, “you do get the best hair and make-up people, and you don’t have to worry about things in rehearsal you might not get if you were making an independent film or if you had a supporting role.”

“On Alien,” she continues, “there was some resentment towards me because I came from New York and got such a good part, the one character alive at the end. That was very difficult for me to deal with.”[48]

[1] Ridley Scott, Q&A with Geoff Boucher, Hero Complex Festival (2010).

[2] Helen Mirren, ‘Helen Mirren on The Tempest and Stealing All Her Best Roles From Men’ by Kyle Buchanan, vulture.com (13th December 2010).

[3] Helen Mirren, Empire (April 2016).

[4] Gordon Carroll, ‘Truckers in Space: Casting’ by Charles de Lauzirika, Alien Quadrilogy (2003).

[5] Sylvester L. Weaver, ‘Sketches of Big Men in Industrial Life: Sylvester L. Weaver Devotes Energies to Civic Upbuilding’, The Los Angeles Sunday Times (Sunday 2nd December, 1923).

[6] ‘Weaver is Parade Center’, The Los Angeles Times (May 4th 1919) p. 6.

[7] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[8] ‘Doodles Weaver, Manhattan’s Favourite Clown, Is a University Graduate Who Earns a Living Imitating Lions, Worms, and Baby Kangaroos’ by Virginia Irwin, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (24th March 1941).

[9] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Sigourney Weaver: Alien Creature’ by Joe Baltake, Philadelphia Daily News (Friday June 8th, 1979) p. 37.

[10] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Independence isn’t an alien concept to Sigourney Weaver,’ Chicago Tribune (Friday 8th June 1979).

[11] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[12] Sigourney Weaver, interview with Bobbie Wygant (1979).

[13] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[14] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Sigourney Weaver rolls with punches’ by Dick Kleiner, The Index-Journal (9th July 1979) p. 5.

[15] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[16] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Independence isn’t an alien concept to Sigourney Weaver,’ Chicago Tribune (Friday 8th June 1979).

[17] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[18] Sigourney Weaver, ‘An Eyewitness Report on Actress Sigourney Weaver’ by Patricia Bosworth, The Santa Fe New Mexican/Family Weekly (August 9th 1981) p. 22.

[19] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Sigourney Weaver Tough Cookie in Alien’ by Richard Freedman, The Indianapolis Star (Sunday June 10th 1979).

[23] Chris Durang, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Sigourney Weaver’ by Jamie Lee Curtis, interviewmagazine.com (23rd February 2015).

[26] Ridley Scott, ‘Truckers in Space: Casting’ by Charles de Lauzirika, Alien Quadrilogy (2003).

[27] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[28] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Sigourney Weaver defends her semi-strip in Alien’, Photoplay vol. 30 no. 12 (December 1979) p. 42.

[29] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Playing Ripley in Alien: An Interview with Sigourney Weaver’ by Danny Peary, Omni’s Screen Flights/Fantasies (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1984) p. 159.

[30] Gordon Carroll, ‘Truckers in Space: Casting’ by Charles de Lauzirika, Alien Quadrilogy (2003).

[31] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Playing Ripley in Alien: An Interview with Sigourney Weaver’ by Danny Peary, Omni’s Screen Flights/Fantasies (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1984) p. 158.

[32] Ibid, p. 158 – 159.

[33] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Alien Interviews: Sigourney Weaver’ by Jim Sulski, Fantastic Films vo. 2 no. 6 (1979).p. 33.

[34] Ridley Scott, ‘Truckers in Space: Casting’ by Charles de Lauzirika, Alien Quadrilogy (2003).

[35] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Sigourney Weaver defends her semi-strip in Alien’, Photoplay vol. 30 no. 12 (December 1979) p. 42.

[36] Ridley Scott, Q&A with Geoff Boucher, Hero Complex Festival (2010).

[37] Gordon Carroll, ‘Truckers in Space: Casting’ by Charles de Lauzirika, Alien Quadrilogy (2003).

[38] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Playing Ripley in Alien: An Interview with Sigourney Weaver’ by Danny Peary, Omni’s Screen Flights/Fantasies (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1984) p. 159.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Roger Christian, ‘Exclusive Preview: Roger Christian’s Cinema Alchemist’ by Roger Christian, shadowlocked.com (27th October 2010).

[41] Ridley Scott, The Alien Legacy (1999)

[42] David Giler, The Alien Saga (2002).

[43] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Dream Weaver’ by Chris Durang, Interview (July 1988).

[44] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Playing Ripley in Alien: An Interview with Sigourney Weaver’ by Danny Peary, Omni’s Screen Flights/Fantasies (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1984) p. 159.

[45] Veronica Cartwright, Texas Frightmare Weekend Q&A (2013).

[46] Veronica Cartwright, ‘Veronica Cartwright Interview’ by David Hughes, Cinefantastique vol. 31 no. 8 (October 1999) p. 36.

[47] Ralph Brown, ‘Alien 3 – Paranoia in Pinewood’ by Ralph Brown, https://magicmenagerie.wordpress.com/2016/10/12/my-pop-life-171-praying-for-time-george-michael/ (12th October 2016).

[48] Sigourney Weaver, ‘Playing Ripley in Alien: An Interview with Sigourney Weaver’ by Danny Peary, Omni’s Screen Flights/Fantasies (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1984) p. 160.