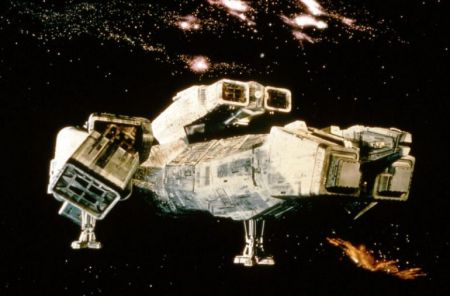

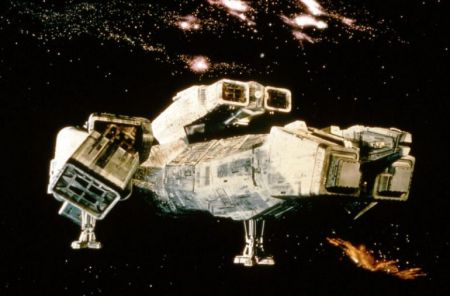

The Nostromo towing its refinery through the inky blackness of space.

“I was really influenced by three films,” Ridley Scott told Fantastic Films in 1979, on the subject of the Nostromo and its claustrophobic corridors. “Not so much in terms of Star Wars, but definitely from 2001 and Dark Star.” The latter film, directed by a young John Carpenter and written by, and starring, Alien writer Dan O’Bannon, was an inverse, comedic take on 2001 – where Kubrick’s film was cold, sterile, clinical, and philosophical in scope, Dark Star was cramped, crowded, shabby, dirty, irreverent and yet also elegiac. “There was a great sense of reality, oddly enough, in Dark Star,” continued Scott, “especially of seedy living. It showed you can get grotty even in the Hilton Hotel if you don’t clean it. Everything starts to get tacky, even in the most streamlined surfaces.”

“When we did Dark Star,” said O’Bannon, “which was in the wake of 2001, we thought we wanted -partly for the novelty, partly because it was realer, mostly just for laughs- we wanted to show this once-sterile spaceship in a rundown condition, like some old bachelor apartment.” For O’Bannon, Dark Star‘s ‘used universe’ was not as strong a visual element as he had hoped, and Star Wars’ “didn’t come across all that clearly either.” For Alien, O’Bannon instructed Ridley Scott that “if we want this spacecraft to look industrial [and] beat-up, you’re gonna have to make it about three times messier to the naked eye than you wanna to see it. And Alien probably was the first time where an audience clearly saw a futuristic machine in a run-down condition.”

The design of the Nostromo and the ‘used universe’ aesthetic would be drawn from O’Bannon’s earlier sci-fi effort, coupled with the realism of Kubrick’s Discovery One. “It’s futuristic,” Scott said of Kubrick’s approach to 2001, “but it’s still hung on today’s reality … In two hundred years things won’t change that much, you know. People will still be scruffy or clean. They’ll still clean their teeth three times a day.” Though Star Wars itself utilised a used universe (or, as Akira Kurosawa called it, a “maculate reality”), Scott wanted to create a tangible reality opposed to Star Wars‘ fantasy-hinged settings and ships. “I wanted to do the truck driver version, the hard-nosed version,” said Scott. “It was supposed to be the anti-thesis of Star Wars. The reality, the beauty of something absolutely about function.”

Before Scott came onto the project as director, writer Dan O’Bannon commissioned his friend and Dark Star spaceship designer Ron Cobb to draw what his script was then calling the ‘deep space commercial vessel Snark’ – a nod to Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark. O’Bannon had promised Cobb a job on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune, but when that film dissolved Cobb, who had terminated the lease on his home and prepared to move to Paris with his wife, was left standing empty-handed. To make up for the letdown, O’Bannon immediately hired Cobb for Alien, which allowed the artist to bounce back from a slump. “He was paid about $400 a week,” Cobb’s wife, Robin Love, told the LA Times in 1988. “We thought it was wonderful!”

When Dan met Ron: “I was working on my first sci-fi film, John Carpenter’s Electric Dutchman, which would ultimately metastastize into the feature-length Dark Star. I tried to reach Cobb to get him to design the whole film, but he was unreachable. For weeks his phone rang without an answer, and then it was disconnected, and then I got his new unlisted number but it was invariably answered by one of the girls who were living with him, who always told me he was out. It was impossible. It took another year and a half to track him down and get him to agree to design us a nice, simple little spaceship for our simple little movie. Finally, one night about ten pm, Carpenter and I drove over to Westwood and rousted him out of a sound sleep. He was hung over from an LSD trip and I felt kind of guilty, but I had to have those designs. We took him over to an all-night coffee shop and fed him and got him half-way awake, and then he brought out this pad of yellow graph paper on which he had sketched a 3-view plan of our spaceship. It was wonderful! A little surfboard-shaped starcruiser with a flat bottom for atmospheric landings. Very technological looking. Very high class stuff.”

“The first person I hired on Alien, the first person to draw money, was Cobb,” O’Bannon said. “He started turning out renderings, large full-colour paintings, while Shusett and I were still struggling with the script – the corrosive blood of the Alien was Cobb’s idea. It was an intensely creative period – the economic desperation, the all-night sessions, the rushing over to Cobb’s apartment to see the latest painting-in-progress and give him the latest pages.”

“I just sat down and started blocking out a ship – which I love to do. Anyway, Dan’s original script called for a small, modest little ship with a small crew. They land on a small planet. They go down a small pyramid and shake up a medium-sized creature. That’s about it. He meant it to be a low budget film, like Dark Star, and I loved the idea. So I did a few paintings and Dan scurried off with them and a script.”

~ Ron Cobb

“And he was doing some incredible stuff,” continued O’Bannon. “Wow! I was really happy during this period, seeing the movie appear under Cobb’s fingers. Of course, we usually had to go over and sit on his back to get him to do any work -otherwise he would just party on with his friends- but how beautiful were the results.”

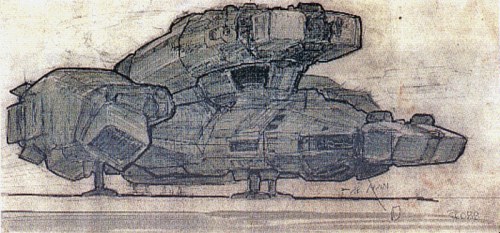

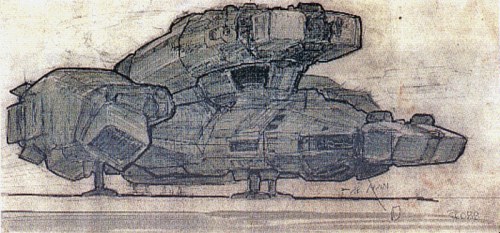

One of Cobb’s early Snark designs.

Coupled with Cobb was English artist, Chris Foss, who O’Bannon had come to know during their tenure together on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune. “Alejandro wanted Doug Trumble to do the special effects [for Dune],” Foss told MTV in 2011, “and of course, Trumble was a big important American, and certainly wouldn’t succumb to Alejandro’s manipulation. So he picked up this gauche American film student, Dan O’Bannon. He was quite hilarious, he said to me once, ‘Hey, these streets are so goddamn small.’ This is Paris, which had some of the widest streets in Europe. Of course, it was only when I got to Los Angeles that I saw what he meant.”

Though Dune would never come to fruition under Jodorowsky, the experience in France influenced O’Bannon’s approach to designing Alien. Jodorowsky had gathered together Chris Foss, Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, and HR Giger to design his film, and the eclectic team would be later reunited by O’Bannon to design his grungy sci-fi horror movie. “Dan said [to Twentieth Century Fox], ‘Hey, we’ve got to get this guy Chris Foss over here.’ So off I went to Los Angeles …

A sketch of the temporarily named Leviathan, by Chris Foss.

Another Foss sketch. The nose and wings of the ship resemble those of the final design.

The early stages of designing Alien were done in an almost ramshackle, low-fi manner. “We were put through shed after shed after shed,” said Foss of the times, “and they were going through director after director after director.” Ron Cobb told Den of Geek: “I soon found myself hidden away at Fox Studios in an old rehearsal hall above an even older sound stage with Chris Foss and O’Bannon, trying to visualize Alien. For up to five months Chris and I (with Dan supervising) turned out a large amount of artwork, while the producers, Gordon Carroll, Walter Hill and David Giler, looked for a director.”

Foss was largely critical of Brandywine’s apparently disinterested approach to setting up the embryonic film. “Walter Hill was very busy smashing cars up for one of his ‘streets’ films,” he told Den of Geek. “He couldn’t be arsed – much too busy! He walked in after months of work and just said, ‘Yep, roomful of spaceships’ and just walked out again.”

Ron Cobb, Steven Speilberg, and aliens: Cobb told bttf.com: “I first met Speilberg when I was working on Alien, at one point Speilberg was considered as a possible director for the original Alien. It was just a brief thing, he could never work out his schedule to do it, but he was interested.” Later, one of Cobb’s early story pitches to Speilberg, an alien horror tale called Night Skies, eventually became 1982’s E.T. Though Cobb cameo’d as one of E.T.’s doctors (“I got to carry the little critter,”) he wasn’t pleased with the family-friendly direction that the film took from his initial idea: “A banal retelling of the Christ story,” he told the LA Times. “Sentimental and self-indulgent, a pathetic lost-puppy kind of story.” Luckily for the artist, a clause in his contract for E.T. (he was originally to direct before the story took a turn) detailed that he was to earn 1% of the net profit. His first cheque amounted to $400,000. Cobb’s wife quipped: “friends from Australia always ask, ‘What did you do on E.T.?’ And Ron says, ‘I didn’t direct it.'”

When Ridley Scott took over the directorial duties, Cobb and Foss were shipped to England to continue their work. Around this point in time, HR Giger was drawing up the film’s alien, and Moebius was commissioned by Scott to design the film’s space suits, which would be brought into reality by John Mollo. The Snark went through a variety of designs, from a ship embedded in the rock of an asteroid, to an upended pyramidal design, to a hammerhead shape and other varieties of ship with white or yellow or more kaleidoscopic paint-jobs.

One of the more unusual designs. “Fanciful Nasa.” By Ron Cobb.

After many months of scribbling and painting spaceships, the production was no closer to settling what the vessel would actually look like. Due to script rewrites, it also changed names, from Snark to Leviathan before the name Nostromo was settled on. “I called the ship Nostromo from [Joseph] Conrad,” Walter Hill told Film International in 2004, “[For] no particular metaphoric idea, I just thought it sounded good.”

However, indecision was still rife on the actual look of the thing.

Scott on O’Bannon: “He’s great. A really sweet guy. And, I was soon to realise, a real science-fiction freak … He brought in a book by the Swiss artist HR Giger. It’s called Necronomicon … I thought, ‘If we can build that [Necronom IV], that’s it.’ I was stunned, really. I flipped. Literally flipped. And O’Bannon lit up like a lightbulb, shining like a quartz iodine. I realised I was dealing with a real SF freak, which I’d never come across before. I thought, ‘My god, I have an egg-head here for this field.'”

Scott on Cobb: “O’Bannon introduced me to Ron Cobb, a brilliant visualiser of the genre, with whom he’d worked on Dark Star. Cobb seemed to have very realistic visions of both the far and near future, so I quickly decided that he would take a very important part in the making of the film.”

Cobb on Foss: “Creating spacecraft exteriors came easily to Foss. His mind and imagination seemed to embody the entire history of the industrial revolution. He could conjure up endless spacecraft designs suggesting submarines, diesel locomotives, Mayan interceptors, Mississippi river boats, jumbo space arks, but best of all (ask Dan) were his trademark aero-spacecraft-textures like panels, cowlings, antennae, bulging fuel tanks, vents, graphics etc. As the months passed, along with two or three temporary directors, Chris began to have problems caused by his spectacular creativity. No one in a position to make a decision seemed to be able to make up their mind and/or choose one of his designs. I think Chris was turning out spacecraft designs the decision makers found too original.”

Ridley himself had input on the design: “I was looking for something like 2001, not the fantasy of Star Wars. I wanted a slow moving, massive piece of steel which was moving along in dead, deep silence … The concept was to have the hull covered with space barnacles or something. I was unable to communicate that idea, and I finally had to go down there and fiddle with the experts. We gradually arrived at a solution.”

Foss paints a more hectic process. “Finally what happened was that the bloke who had to make the [Nostromo] model completely lost his rag, scooped up a load of paper -they had a room full of smashed-up bits of helicopter and all-sorts- and he just bodged something together. So the actual spaceship in the film hadn’t anything to do with all the days, weeks, months of work that we’d all done. It’s as simple as that.”

Cobb explained: “Brian Johnson, the special effects supervisor under pressure to build the large Nostromo model, went into the deserted art department and, out of frustration, grabbed all the Chris Foss designs off the wall and took them to Bray studios. There he would choose the design himself in order to have enough time to build the damn thing.”

However, Johnson had also scooped up Cobb’s art, and though Cobb was concentrating on the designs of the ship’s interior, one of his exterior pieces met with approval over Foss’ designs. “Well I soon found out that Brian found and took all of my exterior design sketches as well,” said Cobb. “About a month later I was told that Brian had used my sketch, ‘Nostromo A’, as the basis for the model, even to the extent that it was painted yellow. Ridley found the colour a bit garish and had it repainted grey.”

Cobb’s grey Nostromo.

“Ridley had his own very firm ideas about what he physically wanted to do,” Foss said of the process, “and he almost studiously ignored everything that had gone before … I kind of got the impression that Ridley was quietly going his own way, trying to get on with it and get it done, a bit like just another job. I’ve just got dim memories of Ridley being like that and really just ignoring months of input … I just have these memories of feeling a bit miffed that things weren’t put together so much better. And poor old Dan O’Bannon, the bloke whose concept it was, just got absolutely shafted. He was almost like patted on the head: ‘Yeah Dan, yeah Dan, that’s cool.'”

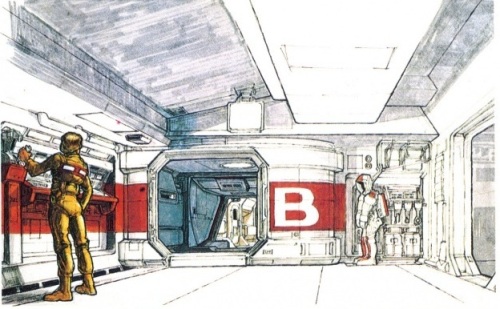

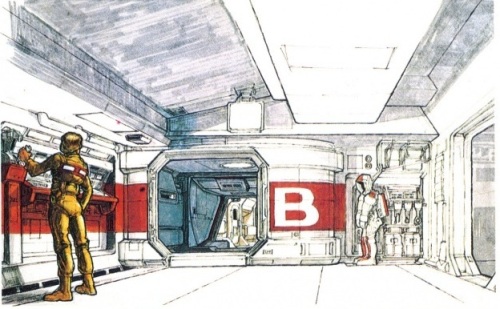

Cobb’s sketches, drawings and paintings for the interiors were also okay’ed by Scott and the production. At first Cobb’s designs were slightly more fantastical, with giant screens and computer readouts and windows covered by protective shells that would open up to reveal alien planets ahead of the ship. Though these ideas were scuppered due to time, money, and logistics, many of Cobb’s early designs and ideas were revisited in Prometheus.

“My first version of the bridge was very spacious indeed; sort of split-level, California style with these huge windows. I had this idea for a spectacular shot where you’d see the approaching planet rolling by on console screens, and then suddenly the windows would open and light would flood in and there would be the actual planet outside doing the same roll as the one on the screen. But it was decided that we couldn’t afford it, and we’d have to go to a Star Trek bridge with no windows and a viewing screen.”

~ Ron Cobb.

“By the time I got to London, Michael Seymour decided he liked the window idea and came up with this hexagon-shaped bridge that was radially symmetrical. Then Ridley wanted overhead consoles, and wanted to make the set tighter, more claustrophobic, like a fighter bomber, and I just started suggesting shapes and forms that would conform to that.”

~ Ron Cobb.

The ship’s auto-doc, as conceptualised by Cobb.

The Nostromo’s life-boat airlock, by Ron Cobb.

In addition to designing the Nostromo’s exterior, its bridge and auto-doc, Cobb also designed the ship’s airlocks, cyro-tubes, corridors, bulkheads, an observation dome (not built), Ash’s ‘blister’ observation unit, some of the film’s uniform patches and ship signage, the ‘flying bedstead’ maintenance vehicle (not built), and even Jones’ cat-box. Cobb told Den of Geek that, “My problem with designing Nostromo’s interiors, the control bridge, corridors, auto doc (or med lab), bulkhead doors, the food deck, etc., was that I grew up with a deep fascination for astronomy, astrophysics, and most of all, aerospace flight. My design approach has always been that of a frustrated engineer (as well as a frustrated writer when it came to cinema design). I tend to subscribe to the idea that form follows function. If I’m to arrive at a cinematic spacecraft design that seamlessly preserves, as in this case, the drama of the script, the audience has to experience it as something impressive and believable.”

“We’re beyond 2001 in terms of scientific advances,” said Scott of Alien‘s futurism, “our capabilities are more sophisticated but our ship’s still NASA-orientated, still Earth-manufactured … in our tongue-in-cheek fantasy we project a not-too-distant future in which there are many vehicles tramping around the universe on mining expeditions, erecting military installations, or whatever. At the culmination of many long voyages, each covering many years, these ships -no doubt part of armadas owned by private corporations- look used, beat-up, covered with graffiti, and uncomfortable. We certainly didn’t design the Nostromo to look like a hotel.”

“I didn’t want a conventional shape [for the refinery,] so I drew up a sketch and handed it to the model makers. They refined it, as it were, and built the model. I originally drew it upside-down, with the vague idea that it would resemble a floating inverted cathedral … I think that the machine that they’re on could in fact be 60 years old and just added to over the decades. The metal-work on it could be 50 years old … I would have liked to see it covered with space barnacles or space seaweed, all clogged and choked up, but that was illogical as well.”

~ Ridley Scott, Fantastic Films, 1979.

The Nostromo model was built under the supervision of Nick Allder and Brian Johnson at Bray Studios, not far from Pinewood, where the live-action scenes were being filmed in parallel with the model shots at Bray. For the refinery, Scott instructed the teams at Bray to make it appear “Victorian Gothic,” with towers and spires and antennae. Bray shop worker Dennis Lowe explained: “At that same time in the workshop Ridley was talking about his first concept of the refinery and he was describing an actual oil refinery with pipes and spires, eventually the term ‘Battleship Bismarck in space’ came up to describe the detailing of the model.”

“I spent a couple of months rigging the Nostromo with neon strips and spotlights that would mimic the Mothership from Close Encounters. These were sequenced using motorised rotary switches, Ridley came over from Shepperton after shooting and took a look at my work then made the decision to scrap the idea – such is life!”

~ Dennis Lowe.

When Ridley arrived after concluding filming at Pinewood, he further revised the ship’s look, removing many of the spires from the refinery, repainting the Nostromo from yellow to grey, and scrapping every piece of footage shot to date, taking it upon himself to re-direct the scenes. “It was a difficult situation,” said Scott, “Brian Johnson was over there [at Bray], working out of context away from the main unit. I could only look at the rushes while I was working with the actors, and that’s not a very satisfactory way of working. In the end, I think a director must be heavily involved with the miniatures, and that’s why I shot them myself.”

According to model builder Jon Sorensen, there were no real hard feelings over the redesigns and reshoots. “Ridley Scott then arrived from Shepperton to take an interest in the models and everything changed radically in terms of tone, colour and look. The yellow was sprayed over a uniform grey. Sections were rebuilt. We started over, discarding all previous footage. There was no anger at this. Surprise maybe. But it was Ridley Scott’s film. We liked him. So we entered the Alien model shoot Part Deux. I recall Bill Pearson and I talking once on what we thought was an empty, lunch-time model stage when a voice spoke from the shadows. Ridley, asking what we were discussing. We answered that maybe that part might look better moved over to there, (we were discussing the refinery). He smiled back and I guess that signalled what was true; we’d go all the way to help him. That night he bought both Bill and I a beer, a move which astonished the Assistant Director, Ray Beckett who complained that in 10 years of working with Ridley, he’d never been bought a beer. So we bought Ray one instead.”

Early shot of the yellow Nostromo approaching the alien planet.

The revised Nostromo hanging in orbit.

The Nostromo interiors were overseen by art director Roger Christian, who had helped craft the sets for Star Wars. Christian told Shadowlocked.com: “I art-directed Alien for Ridley Scott with my team because he was struggling to get the designer and the art department to understand ‘that look’ I created with the dressing on Star Wars … I went into Shepperton, and we built and dressed the first corridor section – actually for a test screen for Sigourney Weaver, who the studios were not sure about. I brought my little team of prop guys who’d understood then the process of what to strip down and how to place it. Because it was not something you just do randomly. It had to be done based on a kind of knowledge.”

“Roger is a brilliant set dresser,” Scott told Fantastic Films. “Though his department was not designing the corridors and sets, their ‘cladding’ of the walls made everything look absolutely real. He would go out with his buyers and prop men and visit aircraft dumps or army surplus stores and drag masses of things in for me to see.”

“With Alien I was able to go much further with the oily and gritty look than in Star Wars,” said Roger Christian, “and for the first time create a totally believable ‘space truck’, as Ridley described it. The set ended up looking as if we had rented a well-travelled, well-used, oily, dirty, mineral carrier – an unmistakably real and claustrophobic space vessel. I think this really helped audiences to identify with the movie, as the characters were so like space truckers, trapped in a claustrophobic nightmare.”

“[The Nostromo’s] like the bloody Queen Mary. Do you get a sense of scale in the interior? That it’s big? We couldn’t build the two to three-hundred foot-long corridors which it would have but it’s supposed to be like one of these huge Japanese super-tankers. Three quarters of a mile long. The refinery behind it god-knows how big. I mean… I dunno. A mile square?”

~ Ridley Scott, Fantastic Films, 1979.

“Ridley saw the ship very much as a metaphor for a Gothic castle,” said Ron Cobb on the subject of the ship’s interiors, “or a WWII submarine … a kind of retro, accessible technology with great big transistors and very low-res video screens.” However, at one point, Scott had other ideas for the Nostromo’s technology: “I wanted to have wafer-thin screens that are plexiglas, that just float on clips -and of course today you’ve got computer screens exactly like that- because I figured that’s where it [technology] would go. I really got those things off Jean Giraud, Moebius, when he’d been drawing and speculating. A lot of his stuff you see thirty years ago is now.”

Cobb acknowledged the Moebius influence, as well as the ship’s other, perhaps subtler, inspirations: “The ship is a strange mixture of retrofitted old technology, a kind of industrial nightmare, like being trapped in a factory … Ridley’s a wonderful artist and he wanted it to look a lot like a Moebius-designed ship, with all kinds of rounds surfaces and with an Egyptian motif.” This Egyptian motif is prevalent in the Weylan-Yutani logo, a wings of Horus design which adorns the uniforms of the crew in addition to their coffee cups, beer cans, etc. The hypersleep chamber also evokes a burial chamber, with the cryo-chambers arranged in a lotus shape. In addition to the Egyptian motif, another influence was Japan. “The owners of the Nostromo are Japanese,” Scott told Fantastic Films.

“The interior of the Nostromo was so believable,” HR Giger told Famous Monsters, “I hate these new-looking spacecraft. You feel like they’re just built for the movie you’re seeing. They don’t look real.”

“As I was working with the art director,” said Ridley, “I decided to make it faintly glittery. I wanted to have sort of anodized gold everywhere. Not steel, gold. Did you know that space landing craft are covered with gold foil? Amazing! So I thought, Why make this out of steel? Let’s make it all warm and oppressive, massive, and gold.'”

The glittery look can be seen in the opening shots of the ship’s computers bleeping into life, and the gold sheen is most prevalent in the ship’s maintenance area, where Brett finds the Alien’s discarded skin moments before his death. Scott explained the design process for the ship’s golden-hued maintenance garage: “We got hold of marvelous, actual parts of actual huge jet engines and installed them, and they’re like a coppery metal with some steel. We used them as four main supports, like columns, and they give a lot of the feeling of a temple. We played the same music we used in the derelict alien craft and we had two temples. The idol I wanted was through these massive gold doors which were as big as a wall, with a gap in them through which the claw [landing leg] can be seen. When that set was dressed, it looked like Aladdin’s Cave … [the garage is] filled with the equipment that the crew would use in their work on and around the refinery, and when they land on various planets – land crawlers, helicopters, other flying machines.”

“Ridley has this lavish, sensual visual style,” summarised Dan O’Bannon to Fantastic Films in 1979, “and I think that Ridley is one of the ‘good guys.’ I really think that he was the final pivot point responsible for the picture coming out good. And so a lot of the visual design and a lot of the mood elements inherent in the camerawork, while they’re not what I planned, are great. They’re just different.”

O’Bannon also nodded to the contributions of Cobb, Foss, Shusett etc., to the picture: “Also, it’s not 100% Ridley either. It’s Ridley superimposing his vision over the cumulative vision of others, you see. Now this could be such a strong director’s picture because Ridley’s directorial and visual hand is so strong. There will probably be tendency among critics to refer to it as Ridley Scott’s vision of the future. And he did have a vision of the future. But it was everybody else that came before, that’s what his vision is … if it sounds like I’m knocking Ridley, I’m not.”

The Nostromo at rest on the alien planetoid.