Ever since 1982 science-fiction fans have looked at Ridley Scott’s Alien and Blade Runner and noted similarities between the two. Many concluded that the two movies at least shared connective tissue, if not universes. Though Blade Runner was not constructed to stand in canon with Alien, the two intertwine not only in terms of aesthetics and thematics, but also share visual and audio cues, as well as behind-the-scenes inspirations that reach both before and beyond either Blade Runner or Alien.

Ever since 1982 science-fiction fans have looked at Ridley Scott’s Alien and Blade Runner and noted similarities between the two. Many concluded that the two movies at least shared connective tissue, if not universes. Though Blade Runner was not constructed to stand in canon with Alien, the two intertwine not only in terms of aesthetics and thematics, but also share visual and audio cues, as well as behind-the-scenes inspirations that reach both before and beyond either Blade Runner or Alien.

“I’m looking for another science-fiction script right now,” Ridley Scott told Fantastic Films in 1979, shortly after completing Alien. “Something that has a little bit of speculation or prediction about it, rather than just a thriller. Purely, as an art director, I find the the whole area of hardware and environment fascinating. One day I’ll do a film just about people, hardware and environment. Actually, that’s what science-fiction is all about, isn’t it?”

The project that Scott next latched himself onto wasn’t Blade Runner, but Dune, a film which, under Alejandro Jodorowsky, helped to introduce many of Alien’s creative team to one another. Dan O’Bannon was introduced to Chris Foss, HR Giger and Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud during Jodorowsky’s attempt on the film, and all four moved on to craft Alien’s characters, creatures, vehicles and environments – now, in an amusing case of synchronicity, Alien’s director was tackling Dune, and he took Giger along with him.

Unfortunately for fans of Herbert’s novel, Dune collapsed again, this time after Scott pulled out due to the death of his older brother, Frank. However, Scott found that working helped him to grieve, and he took another science-fiction film under his wing; an adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, for now titled Dangerous Days, and later known as Blade Runner.

Though Blade Runner existed in a world quite distinct from Ridley’s 1979 effort (that is, they share no continuity) it still found itself being informed by Alien as well as that film’s creative contributors. Firstly, Scott’s vision for the film was drawn directly from a strip penned by Dan O’Bannon and inked by Moebius during their Dune days. “We had [Moebius] working a little bit on Alien, and I tried to get him involved in Blade Runner,” Ridley revealed to Film Comment magazine in 1982. “My concept of Blade Runner linked up to a comic script I’d seen him do a long time ago; it was called The Long Tomorrow, and I think Dan O’Bannon wrote it.” The Long Tomorrow would also influence some imagery in Prometheus.

The most notable and obvious onscreen relationship between Alien and Blade Runner was in the grungy aesthetic employed by Scott. In Alien the Nostromo is cramped, dirty, oily, and battered. In Blade Runner the city is an amalgamation of crumbling stone and retro-fitted tech. “We’re in a city which is in a state of over-kill, of snarled up energy,” explained Scott, “where you can no longer remove a building because it costs far more than constructing one in its place. So the whole economic process is slowed down.” This meant that the towers and apartment blocks of the film were in a state of half-collapse, half-construction; old brick and cement infused with new steel girders and soaked in neon light.

Looking over the smoke and grime of Los Angeles, Scott quipped that, “This [film] kind of followed through on Alien, because there was almost like a connective tissue between all the stuff I went through on Alien, into the environment of the Nostromo, and people who still have Earth-bound connections … this world could easily be the city that ports the crew that go out in Alien. In other words, when the Alien crew come back in, they might go into this place and go into a bar just off the street where Deckard lives. That’s how I thought about that.”

Indeed, it’s not hard to imagine Dallas sulking at Taffey’s, or Parker mending a spinner.

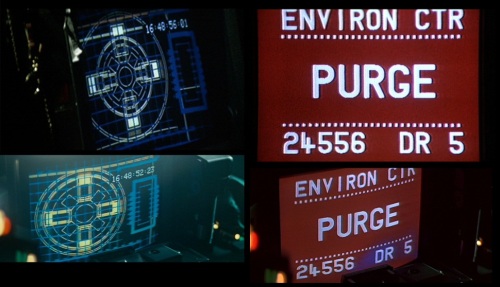

The most famous of Alien and Blade Runner’s connective tissue are the latter’s visual homages. Screens from the Nostromo’s monitors appear within the spinner vehicles. Top images are from Alien, the bottom from Blade Runner.

Other Alien/Blade Runner parallels include the role of corporations in the future. Scott imagined that companies would become bigger than legitimate political institutions and would act as de facto governments. These industrial imperialists would hold monopolies over property, robotics, space-travel, off-world colonies, the terrestrial police, paramilitary units and even, in the case of the replicants and the androids of Alien/s, the creation of life.

In an 1984 interview, Ridley Scott said in regards to the corporate worlds of Alien and Blade Runner: “Here you see a large corporation that does something in one area buying up another corporation that specialises in an entirely different field. Obviously two separate sides of the conglomerate world -perhaps engineering and biochemistry- will eventually merge, just as I think industries will develop their own independent space programs.”

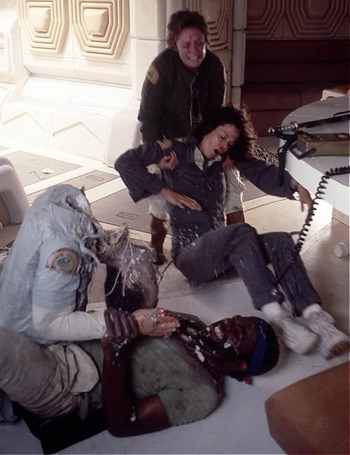

Sound effects from Alien also returned. Alien/Blade Runner editor Terry Rawlings revealed that “There’s this low, monotonous, humming noise you hear every time you’re in Deckard’s apartment. It’s there all the time, but you don’t know where it’s coming from until the end of the picture. Then Harrison discovers Sean Young sleeping under the sheets in his bed, and you realize that that sound has been coming from these two flickering TV monitors besides Deckard’s bed. Well, in that particular case, we reused a sound effect originally created for Alien. It had been done by a terrific sound editor chap named Jimmy Shields; Jimmy had initially cooked up the sound you hear in Deckard’s apartment for Alien’s Autodoc, the automated medical scanner John Hurt’s put under after the facehugger clamps onto his head. The reason we reused this audio bit for Blade Runner was because Ridley just liked the sound of it. It was so dynamic, it really stood up and hit you in the ear. Or tickled it, as the case may be.”

Blade Runner and the Alien series continued to intermingle throughout the 80’s and 90’s. Syd Mead, who had designed Blade Runner’s cityscapes, was recruited by Aliens writer/director James Cameron to design the Sulaco and its interiors. Though it can’t be seen onscreen, Dallas’ profile during the inquest sequence details his prior work and transits for one Tyrell Corporation.

Androids, Replicants, and dangerous days: Neither Alien nor Aliens explored the roles and social statuses of their respective androids, but the plight of Roy Batty and his replicant cohorts informed, in some small way, the performance of Bishop actor, Lance Henriksen.”When I got the part,” he said in 2011, “the first thing I did was look at actors who’d played characters like that, Rutger Hauer in Blade Runner, Ian Holm in the first Alien. They were phenomenal.” Earlier, in 1987, Henriksen had told Starlog, “I read a couple of books [for Aliens].” One book, Mockingbird by Walter Tevis, gave Henriksen an idea of Bishop’s unseen struggle with his artificial nature that reminds one of the elegiac mood hanging about the replicants. “There’s a bit in it where the android knew how to play a piano,” Henriksen explains, “but didn’t know why. He didn’t know what music was, but he kept hearing it. It was part of his builder’s input that hadn’t been completely erased. That image stuck in my mind, and what it translated to me was that there were feelings that Bishop didn’t understand, like a joke.”

Henriksen also alluded to technophobia in the Alien-verse: “For [Bishop], the world is xenophobic. He’s an alien to anything alive. He must be as careful as, say, a black man in South Africa, where you make a mistake and you’re out.” Henriksen concluded by saying, “You’re either replaced or you’re destroyed,” an allusion to Deckard’s “They’re either a benefit or a hazard” line.

In addition to being a theme of Blade Runner, technophobia, persecution, and Ludditism were points in William Gibson’s Alien III, and similar themes also swiveled around Prometheus’ David.

For Alien 3, David Fincher hired Blade Runner’s director of photography Jordan Cronenweth, solely based on his work on Scott’s movie. Unfortunately, Cronenweth’s struggle with Parkinson’s Disease caused Fincher to release him from the film, only two weeks into shooting. Rumours abounded that Twentieth Century Fox had strong-armed Fincher into firing Jordan, but the director ploughed on with Alien 3 with Alex Thomson serving as cinematographer.

Blade Runner managed to bleed itself into other areas of Alien 3. Though Ridley had envisioned the Nostromo and Company as being one-part Japanese, his film never made this overt. Los Angeles in Blade Runner however capitalised on the idea. The streets are strewn with Asian bicycle riders, lanterns, lingo, graffiti and advertisements. Seeing this, Fincher decided to make Weyland-Yutani’s presence on Fiorina 161 reflect its Japanese heritage; as such, the company’s logos in the film are accompanied by kanji, as do soda machines and other props scattered around the film. They usually translate as “Weyland Yutani kabushiki-g/kaisha”, meaning “Weyland Yutani joint-stock corporation”. Another obvious example is the large red lettering in the prison scrapyard.

-this shot of Fiorina’s hellish machinery. “A pretty nice Blade Runner-esque shot,” according to Richard Edlund of Boss Film.

Alien 3 matte painter Paul Lasaine added a Blade Runner homage in his painting of the Fiorina refineries, where distant towers styled after the stacks from Blade Runner‘s famous opening shot were included in the background – which you’re unlikely to have a chance of spotting in Alien 3 due to the overlapping effects and the diminutiveness of the painted towers. Allegedly, the Tyrell Pyramid structure is also in there, somewhere.

When Ridley returned to the Alien-verse with Prometheus, he also considered featuring some allusions and outright references to Blade Runner. “There’s one idea that I’m very sad that we didn’t do,” explained Prometheus concept artist, Ben Proctor. “Ridley, one day, came in and said, ‘You know, I’m thinking what if it’s the Weyland-Tyrell Corporation? Is that cool?’ Maybe the bodyguards, you know, that come out with Weyland, maybe one of them says Batty on his uniform. And we’re like ‘Awesome! Do it, do it!’ And it didn’t end up making it but I thought that was a really cool thing that there is such a compatibility between the sort of, you know, dystopian future of Blade Runner and Alien that they may as well be the same universe. And if we’re doing a Weyland versus a Weyland-Yutani, why not have corporate mergers shifting and make some kind of a connection there. I thought that was cool.”

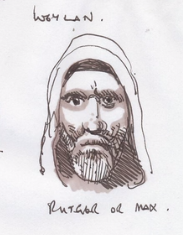

But a role as a military man wasn’t the only piece of connective tissue that was planned for Prometheus, as Ridley had toyed with the idea of casting Hauer as Peter Weyland.

Ridley’s sketch of Weyland. “Rutger or Max,” it reads. Rutger Hauer and Max von Sydow were originally considered for the role.

Ultimately no nod to Blade Runner made it into the film, but an ode of sorts did make it into the home release, courtesy of Alien Anthology/Blade Runner/Prometheus DVD/BD producer Charles de Lauzirika. A memo dictated by Peter Weyland reads:

“A mentor and long-departed competitor once told me that it was time to put away childish things and abandon my ‘toys’. He encouraged me to come work for him and together we would take over the world and become the new Gods. That’s how he ran his corporation, like a God on top of a pyramid overlooking a city of angels. Of course, he chose to replicate the power of creation in an unoriginal way, by simply copying God. And look how that turned out for the poor bastard. Literally blew up in the old man’s face. I always suggested he stick with simple robotics instead of those genetic abominations he enslaved and sold off-world, although his idea to implant them with false memories was, well… ‘amusing’, is how I would put it politely.”

The easter egg attracted much attention online. However, Lauzirika told movies.com that the memo was only a gag, and not intended to be taken seriously:

‘That was me having fun and being cutesy. I wrote all that stuff. I actually said this at the press conference they had in London, which is that if it’s in the film, it’s canon. I would argue that the viral pieces that are included in the Peter Weyland Files are canon just because they originated with Ridley and Damon Lindelof. I would say those, to some degree, are canon. But anything else – especially these which are kind of like little cute, embedded text graphics on the menus – I wouldn’t take those too seriously. It’s just meant to be an in-universe framework for those viral pieces.

As a Blade Runner fan, and because there’s been so much talk before this even occurred with people on the Internet speculating that maybe Alien and Blade Runner and Prometheus could all exist in the same universe, it was just more of a wink at that. Absolutely nothing to be taken seriously. I mean, I sent it to Ridley and he had no comment. [Laughs] So, it’s just icing on top of icing. It’s not the cake. It’s a fun, little side thing that’s very superficial. And, by the way, it in no way officially establishes that it’s Blade Runner because, if a lawyer were to comb through that, there’s no reference to Tyrell or anything in Blade Runner. It’s just a very lightly intentioned joke.”

~ Charles de Lauzirika, movies.com, 2012.

One last thing: in the 1980’s rumours of a Blade Runner sequel surfaced – to be directed by James Cameron. “I have nothing to do with Blade Runner II,” Cameron told Starburst magazine in 1989. “I wouldn’t be interested and I don’t want to go around cleaning up after Ridley Scott for the rest of my life!”

Alien/Blade Runner banner created by Space Sweeper. Many thanks.