After three years, three different screenwriters and an assortment of drafts and directors, Alien III finally began to take some crude sort of shape. Plot and design elements were beginning to take hold, and though Ward’s script was never made per se, many of the decisions made here would ultimately affect or appear in the final movie. The decision to kill off Hicks, Newt and Bishop was made here, as was Ripley’s isolation among an imprisoned monastic order, her Alien pregnancy, and a denouement featuring a final sacrifice.

Still, progress was glacial and expensive. The pressure to deliver a worthwhile successor to Aliens was running high. The production had recently lost its director, Renny Harlin, who felt frustrated by a lack of creative control and went on to direct Die Hard 2 instead. For a moment the film was mired in production hell yet again, but when producer David Giler saw The Navigator: An Odyssey Across Time he was impressed enough to seek out the film’s co-writer and director, New Zealander Vincent Ward, and quickly hired him to direct their hindered Aliens sequel.

“At the time I was working on Map [of the Human Heart] with my co-writer,” Ward told The Independent in 1993. “I was broke, I’d spent a lot of money on going to the Arctic and interviewing anthropologists and dam-buster bomber pilots, and we were driving each other crazy. I was living in this basement in Australia, and the phone call came and I turned it down. But then they rang me back and said, ‘We’ll send you the script anyway.'”

But Ward was unimpressed. “I read it, I said ‘no’ again. And then they rang me back a third time, and said, ‘You can change the script if you like.’ Well, by this time that basement was driving me crazy, so I said yes just to get out.’

Free of David Twohy’s prison-station script, Ward was on a plane for Los Angeles when he struck an idea for the film. “After The Navigator I wrote a book [Edge Of The Earth],” he told Empire magazine in 2009, “and started exploring more medieval imagery, and I came across engravings and so on that I hadn’t seen before. One of them was of a devil being cast out of someone’s mouth. So on the plane over some of these images came to mind. By the time I got to LA, I had a complete story.”

He explained to The Independent that “It struck me that it would be possible to take the elements of the Alien story and overlay a whole Christian mythos on it, and it would fit perfectly. So these monks see a star in the East, which is Ripley’s escape craft, and it crashes down in a lake, and you carry on from there.”

Somewhat to his surprise, the producers liked his bizarre idea. Ward’s story would take place on a quasi-medieval wooden orbiter: Lindisfarne in space. “It was like a Bosch world,” he explained, “It had a lot of technology at the centre of it, controlling basics like gravity and air, but it was all rotting, and the surface world was like second century AD Turkey, controlled by an ascetic sect of monks whose buildings and machines were all made of wood.”

RELIGIOUS COLONY ARCEON

——————————————-

POPULATION: 350 exiles

CRIME: Political heresy

~ Alien III, by Vincent Ward & John Fasano

“It was sort of a retro film,” Ward explained. “[Ripley] was with monks in a strange wooden orbiting vehicle… With a monk commune, in a wooden orbiting satellite, really. [The monks] decided to do everything the hard way, because they were monks, but they did have basic technology so they could survive. Then, in a world where people believe in devils – where she doesn’t, comes the Alien. I think it would’ve been quite amazing.”

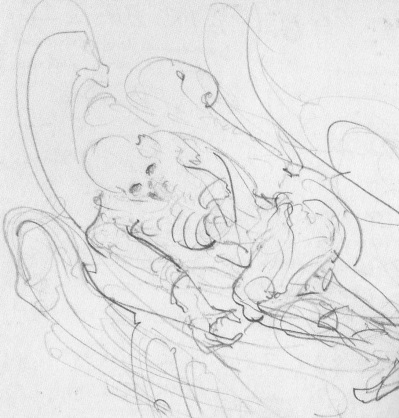

The Alien, the devil and the dragon: Ward wasn’t the only person who had thought of the Alien in an historical and mythological manner. In an interview with Don Shay, Ridley Scott commented:

“We’d always talked about and played around with the idea of the absolutes – of good and evil. And if the Alien was really … what was it? Was it the face of the Devil; was it the face of the demon? Because if you look at historical manuscripts, engravings, and pictures, from wherever they come from whether; it’s China, whether it’s Europe, whatever the nationality, there’s a kind of continuity of the idea of the demon, as there is about the dragon.

So, [Alien was] like taking off the mystical aspects of it and saying it’s nothing to do with [myth]; it’s a biological fact, it’s a biological creature, and it’s been here before.”

Despite its strange take on the Alien series, those involved with crafting the film were genuinely interested in exploring Ward’s angle. “I liked him immediately,” said the film’s production designer, Norman Reynolds. “He was very enthusiastic; he had lots of ideas. We looked at some images he was really excited about: the fires of hell, all that sort of stuff. It seemed a really interesting way to go with Alien.”

However, it is also true that many couldn’t wrap their heads around how a satellite made of wood could sustain life. Vincent Ward explained that the satellite was not made of wood, only covered in it, like scaffolding that had grown outwards from a technological core. The orbiter was originally quite ordinary, but it was modified it to resemble an ancient abbey. The monks themselves were to be exiles from Earth, and included political criminals among their ranks.

“What if you had like a sort of powerful sect on Earth (in the future of the Alien movies) who reject all technology beyond a certain date. So the ruling forces say to the sect, ‘Okay, you wanna live this way? We have an old satellite – huge thing. We’ll tow it into outer space and you can just live there on your own.’

They just give them a place to live where they know inevitably they’re gonna die. The sect agree, but they believe in having an environment that looks archaic. Within that environment -a huge, round satellite about a mile in diameter- you have maybe 16 floors, each one about 100 metres high. It’s layered like an ant’s nest, or bee’s nest, and each layer has been largely clad with huge areas of sculpted wood. They can grow wheat there, and even have windmills and orchards. In a way it’s like a monastery.

The satellite [named ‘Arceon’] has a range of technologies that allow it to survive in outer space: it has a means of dealing with gravity, and a means of dealing with air, and it has a low surface atmosphere. It looks like a meteorite on the outer surface.’

~ Vincent Ward, Empire magazine, 2009.

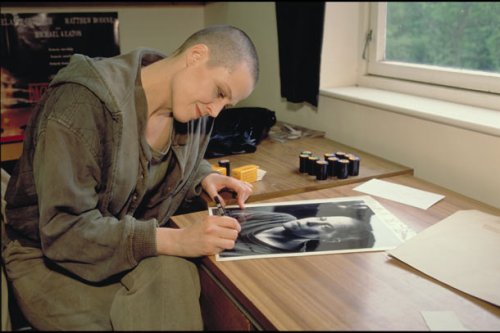

The wooden world under construction. Wooden panels and struts slowly envelope a technological core; the source of the station’s life-support systems and gravity.

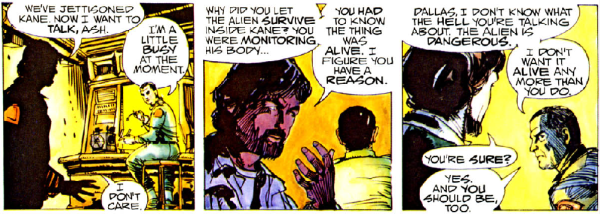

Before we get to the story synopsis, let’s take a look at (and get out of the way) one of Alien 3′s most infamous legacies, the killing of Aliens’ characters, and where it all began, right here, in Ward’s story.

Ward’s script begins with a scene familiar to Alien 3 viewers (the evacuation of the Sulaco) though with some key differences. The Sulaco is under siege by Aliens, and Ripley and Newt are awakened from hypersleep. They record an SOS message before abandoning the ship in an EEV:

“…taking pod four. The crew of the SS Sulaco and all Marine commandos are dead. Ship’s sensors have interrupted the hyper sleep cycle. An overlooked Alien egg has hatched. Bishop and Hicks have been killed. Xenomorphs have infested the cruiser. Newt and I are taking pod four. The crew of…”

As we know, the EEV crashes, killing Newt but sparing Ripley.

The script does not provide any explanation for the appearance of an Alien egg aboard the Sulaco, which remains a point of contention for the third movie even today. The script explains that Hicks and Bishop are subsequently killed by “Xenomorphs”. No real details are provided.

Ward’s decision to kill off Aliens’ supporting characters had, for him, a degree of emotional logic that would run throughout the film. Though he was apparently enamoured with Cameron’s parental theme, he wanted to give the film a parental theme of his own, supplanting Newt with an Alien embryo and adding nightmarish visions of Ripley’s dead daughter, Amanda (‘Kathy’ in this script, somehow). “One of the first things I wanted to do was kill [Newt] off,” Ward explained. “She kind of annoyed me.”

Ward explained that his motivation for killing Ripley’s adopted ‘family’ was necessary to explore the mindset of someone suffering from loss and their subsequent quest for personal redemption – not unlike Ripley’s previous arc in Aliens. “You can’t keep living your life fighting creatures without much of a family,” said Ward. “How would you survive? Families give us something. We’re communal, social creatures. So Ripley’s big regret is that she missed out on a personal life. She seeks some sort of strange atonement for not having had a relationship with her daughter.”

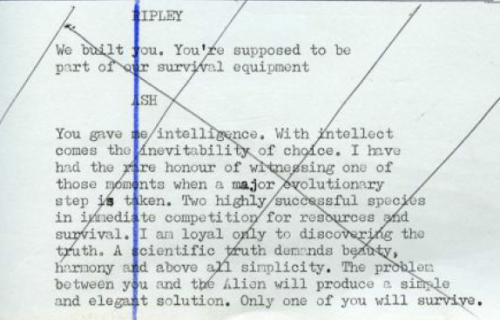

Ripley’s impregnation was to be a mockery of her parental desires. Her family is destroyed and then replaced by the Alien. “It was effectively father to the embryo inside her,” said Ward, “and so therefore would not want to destroy her during its gestation.”

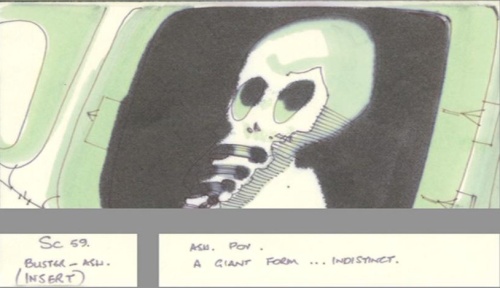

Her pregnancy would also inflict her with nightmares and strange hypnagogic visions of the Alien and her dead daughter. In one sequence, the Alien leers at her and sizes up almost for a kiss. “The thought of that creature licking at her would be truly frightening and kind of wonderfully revolting, sexual and protective at the same time, even if it was only in her nightmare. It would make you feel she had gone to hell and back, and when she finally kills it the satisfaction would be very primal.”

The image of the Alien leering in at Ripley, lips pared, tongue extended, later became one of the film’s strongest images, and was even featured in promotional materials and the trailers.

Now, on to the plot of the film…

SYNOPSIS

Cast of Characters

Major characters

Ellen Ripley – returning from Aliens.

Brother John – one of Arceon’s monks. Forty-ish, bookish, solitary. A proto-Clemens.

Brother Kyle – another monk. Black, early fifties. A proto-Dillon.

Mattias – Brother John’s grizzled dog.

The Abbot – leader of the monastery. Appears kindly but is authoritative. Can be considered Ward’s equivalent to Superintendent Andrews.

Anthony – an android banished to the monastery’s sub-levels.Other named and unnamed characters feature, but are either insignificant to the plot or are mentioned offhandedly.

The movie begins with the intention of beguiling the viewer into thinking they are watching a medieval scene. Inside a glass furnace several monks blow and shape the molten glass. One monk, Brother Kyle, observes one of his fellows, Brother John, entering the works, and welcomes him with song. John does not reply. Instead he tends to a burned monk. Kyle continues to mock him with song:

Brother Kyle: Tend you quickly he will, with bottles from a shelf.

But heals not, so easily,

The ills which plague himself.Brother John stops stirring.

Brother John: (to Kyle) Enough.

Despite Kyle’s jibs and John’s impatience, they are in fact quite amiable with one another. Kyle compliments his treatment of the burned monk, but John opines that he is no ‘Father Anselm’, a recently-deceased monk who was the Abbey’s Physician; a position that John himself would like to obtain.

We find out more about John in the next few scenes. The film assumes him as its protagonist. We see his living quarters, his “old worn out” dog, Mattias, and also John’s predilection for the library and several of its tomes. The Abbot appears in the cordoned area of the library, but allows John to borrow the book due to his treatment of the burned monk in the glassworks. “Father Anselm was… an unexpected loss,” says the Abbot. Then he adds, with an insinuation of a future promotion: “You’ll do fine.”

John takes the book at the Abbot’s insistence and leaves to find somewhere else to read. We are then given a tour of the wooden abbey as John and Mattias walk through it.

There is the bell tower with its ropes and cogs; the abbey floors thick with sandy dust, and then the films reveals its most infamous environment:

The door has opened onto the surface of a planetoid!

The curving horizon broken only by the very top of the Abbey bell tower poking through the levels below. Smoke curls from vents set into the surface. Sunken areas of the planet’s surface are seas.

This is Arceon. A man-made orbiter. A shell of lightweight foamed steel, five miles in diameter.

Constructed by The Company on Special Order, with the habitable levels within finished in whatever material suits its end user.

Here, on the top of the world, John and Mattias revel in the “celestial light” and the thinner, but fresher air. They walk to the shore of an artificial sea, where they sit and watch the stars.

After a moment, John begins to read aloud to Mattias. The book is the memoir of a monk living in a thirteenth century monastery that had been beset by the Black Death. “I stayed as long as I could bear it,” John reads, “then with my dog [I] fled.”

Rather ominously, the book’s text was finished by another hand, hinting that the author did not survive. John, somewhat disturbed, closes the book. It will prove to be prophetic, but for now he is again looking to the heavens.

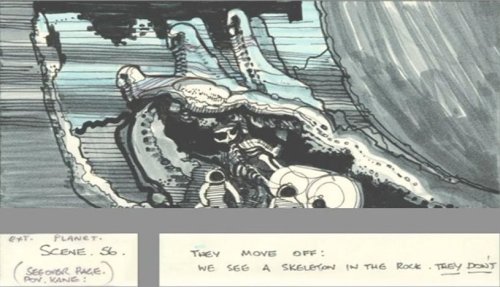

Suddenly, he sees:

One of the stars.

Brighter than the rest.

Moving.

Fast enough to leave a faint trail.

Across the stars.

And down.

A comet…

John and a band of nearby monks all gather to watch the comet’s descent. It takes days to approach, but by the time it roars overheard three hundred monks have gathered on the surface to observe it. The comet trails fire above them. “John holds up his hands – to touch a star – skin blisters as it passes over him.”

The comet crashes in the lake. John is the first there, leaping into a coracle to row to the impact site. He finds that the comet is in fact an emergency escape vehicle. He climbs in despite the protestation of the other monks. Inside he finds blood, shredded clothing, the head of a child’s doll, and two cryotubes – one smashed and empty, the other still harbouring its occupant. Ripley.

Brother Kyle boards the EEV and together he and John remove Ripley from her pod and carry her into the coracle. Kyle admonishes John for entering the vehicle but the latter is too amazed by the technology within to care.

Ripley is left to recuperate whilst the monks tow her EEV from the water. Ripley later opens her eyes to find John asleep in her room, having kept watch over her. Suddenly, an Alien emerges, glides over to her, and lays one hand over her abdomen and cocks its head. “The implication is clear,” reads the script. She screams – but it was all a dream. John eases her back to bed, where she again falls unconscious.

When she comes to she scans her surroundings and looks outside where she sees:

Garden of Earthly delights…

Monks labouring under a beautiful, celestial blue sky…

picking apples, fishing on the water on small inland lakes,

working with hammer and saw on small wooden cottages. Lyrical.

But the environment is quickly revealed to be a facsimile:

Workers on a scaffolding

with crude brushes at the end of poles paint the sky blue.

The abbey, the cottages, the fields outside her window are all on one level – inside the planet!

The vaulted ceiling, painted to look like the sky with huge glass ‘windows’ to allow the sunlight in,

is actually the underside of the planetoid’s outer shell.

The Abbot enters her room. Ripley looks around and, to her relief, finds John there also, standing in the doorway behind the Abbot. John’s presence and demeanor comfort her, not unlike Clemens in the final movie. The Abbot introduces himself and explains the purpose of the monastery and the monks within it:

“This is the Minorite Abbey within the man-made orbiter Arceon … We are a monastic order that has renounced all modern technology. We live the old way. The pure way.

Ripley then asks for Newt, and is told nobody other than herself was found. She then panics about an Alien infestation, and attempts to explain the events of Aliens, but the Abbot cuts her off at the mention of Earth – “Not possible,” he says, explaining that:

“When we left Earth seventy years ago, it was on the brink of a New Dark Age. Technology was on the verge of destroying the planet’s environment. A computer virus was threatening to wipe away all recorded knowledge. There didn’t seem to be any way it could be averted. In the almost forty years since we were towed out here in hypersleep, the news that came with occasional supply ships only got worse. Finally, the ships stopped coming. We had to resign ourselves to the fact that worst had come to pass, and the Earth no longer existed.”

Ripley continues to rave about the Alien, and the Abbot’s patience evaporates. He demands she say no more, and assigns two “burly monks” to guard her door. Entry is forbidden, even to Brother John.

That night John falls asleep in the library. Another monk barges in, hysterical, and tells him that Sandy, his sheep, is ill. “All creatures great and small,” John mumbles, grabbing his medical kit.

When the two monks arrive at the barn, Sandy the sheep is convulsing in agony. The following scene could have come straight out of Eric Red’s Alien III script: the sheep convulses and the two monks watch as it explodes in a shower of gore and an infant Alien emerges from the carcass:

“It shows the characteristics of the animal in which it has gestated. Tiny razor sharp teeth and black, glass-like eyes peer from an elongated head covered with downy, but gore-matted WOOL. A quadruped, its shrunken hind legs struggling to free itself from the cooling morass of intestines.”

The hysterical (and bereaved) monk attacks the Alien with a pitchfork. A fire erupts, and the Alien is thrown into the flames. John and the monk leave in shock while the barn collapses like a pyre.

Meanwhile Ripley, who can see the barn burning from her quarters, leaps out of bed only to be assaulted by four burly monks, who escort her to a tribunal overseen by the Abbot. The monks accuse her of bringing a pestilence to the satellite, though Ripley’s warnings about the Alien still go unheard. The Abbot decides to have her interned in the bowels of the monastery, which the other monks promptly carry out. Afterwards John corners the Abbot and protests, but the Abbot brushes him off.

Meanwhile, in Ripley’s subterranean cell, a face appears in a hole in the wall: “bright, wrinkled eyes beneath a snowy white crew-cut” peer at her from the cell next door.

We cut back to John who, after having an apparent epiphany whilst researching medieval depictions of Satan, decides to approach the Abbot once again – and spies him ordering John’s silent arrest. The monk who alerted John to the sheep’s condition is likewise condemned and taken away, and John susses that the alleged offence is having witnessed the birth of the Alien in the barn. For now, John decides the best option is to approach Brother Kyle in the glass-works. Unfortunately, John’s frenzied state alerts the other monks, and he flees the scene.

He decides to enter the subterranean levels of the wooden world, and takes a secret passage down.

LADDERS

Extending down through huge open areas beneath the upper level.

Past vast underground viaducts held up by wooden rafters.

Beyond that – a great underground sea that marks the centre of

the planet – below that, the cells.

And Ripley.

At this point we cut to one of the script’s better known set-pieces: the bathroom.

As the Abbot and a ‘Bald Tribunal Member’ occupy the stalls, an Alien reaches up and yanks the latter down through the hole in the ground, and drags him under the floorboards. The toilet’s faucets and lavatories “reject a torrent of gore! Blood and viscera spraying the wall – converting the Abbey into an abattoir.”

The script does not tell us where this Alien comes from – the sheep-Alien having been killed in the barn. There is no insinuation at all that they are the same creature. If it stowed away on the EEV, there is no indication in the script. Perhaps its appearance was something to be sketched out more thoroughly in a later draft; still, it shows the carelessness of the plotting.

We catch up with Ripley and the head in the hole. The white-haired man is Anthony, an android. Anthony urges Ripley to eat and restore her strength, then to fight back against the monks. They are interrupted by John, who bangs on the cell doors in search of Ripley. He opens Anthony’s cell and enters. The two know one another.

John: Anthony? Thought you dead fifteen years.

Anthony: Made too good for that. What’re you doing?

John: I – I’m looking — the Abbot –

Anthony: What? You look like you’ve seen the devil.

Ripley (o/s): He has.

Ripley deduces that John has seen the Alien, and demands that he leave. She invokes the slaughter of the Nostromo and Sulaco crews: staying with her means certain death. “It never ends,” she says.

This conflict is set aside, and we cut to John, Anthony and Ripley working through the subterranean corridors. They discuss the nature of the Alien along the way:

Anthony: It must be able to take on some of the characteristics of the animal it grows in. Maybe they are from some sort of aggressive soldier race – warring parties drop the eggs on opposing planets-

Ripley: And the Alien takes on the form of the creature that finds it, assuming that animal is the dominant life form on the planet. So when it gestates in a man-Ripley shudders at the memory.

Anthony: It’s a biped. In a sheep or cow, a quadroped.

Ripley: Shit. I just didn’t think it could do that to animals.

John: Wait a minute – I thought you were the expert on this monster.

Ripley: Is that the only reason you came to get me out? Because I knew about this thing?

John: Yes. I mean no. I mean, that was part of it. Look. I never thought you were wrong. I was wrong not to say anything. I was afraid to speak up. It’s hard to be a monk, you know?

John also explains that Anthony was a spy placed on the wooden world by The Company, and Anthony reveals that the world is not intended to be a monastery, but a prison, and that its inhabitants are all political exiles. John and Anthony both elaborate:

John: The order was more of a counter-culture, a reaction to the technology that was beginning to take over everyone’s lives. It was a simple enough idea – read, don’t watch disc. Walk, don’t pump more carbons into the air. The earliest members denounced technology. Started to collect the remaining books. Nobody would have noticed if it hadn’t been for the virus.

Ripley: Your Abbot talked about that. The New Plague.

Anthony: A computer virus. A bad program. By the time the corporate structure was trans-global, all the world’s data storage systems were linked. It spread through two countries before it was stopped.

John: After a scare like that, thousands flocked to our retreat. People started clamouring for written information.For our books. They abandoned the modern ways-

Ripley: I think I can see how this comes out. They abandoned their possessions.

Anthony: This was a threat-

Ripley: To the Company.

John: A movement to live simply was quickly twisted by Federal agents into a political movement against the Company-controlled world government. Too much was at stake.

Ripley: Too much profit.

John: We were sentenced as political dissidents. This orbiter is our gulag. All the men were packed up with all our books, and towed into space. Ten thousand men. The eldest died very quickly.

Ripley: The Company had a sense of irony. Sending you out on this wooden tub.

Anthony: I was placed among them as a sensor. Keep tabs on the movement.

Ripley: So how’d they find out about you.

Anthony: I told them. After the supply ships stopped coming I saw no point in keeping up the charade. Since I was a sort of walking reminder of technology, they cast me down.

The scene certainly illuminates the strange concept of monks in space, though it does carry a very bizarre notion of political sentencing, and Ripley’s interjections do nothing but make it clear to the audience that corporatism and capitalism are still pressing themes in the series, (Weaver would complain about the quality of Ripley’s dialogue. More on that later.).

Ripley is quick to inform John that the Earth was not destroyed after the exile of the dissidents, but he still seems doubtful. She further reminds him that was was right about the presence of the Alien. They discuss the layout of the monastery, which is split into three ‘levels’: Heaven, a sea, and Hell below it. They also discuss the need for, and lack of, heavy artillery, and the presence of technology in the orbiter:

Ripley: This is a man-made planet. Something has to be circulating your air, your water.

John: God?

Ripley: Please.

John: I don’t know, I just took it for granted.

Anthony announces that there is technology in the satellite, a room where fresh air and water is produced; it is the “heart and lungs of Arceon.” The three resolve to head there, and Ripley announces that she will help the monks escape the Alien, but will avoid confrontation with it. “I’m not going to fight this thing to end up alone again,” she declares.

At this point she feels the first pangs of the Alien embryo inside of her. As she does in the movie, she writes off her bad turn as an effect of interrupted hypersleep.

Back to the Abbot, and it seems that the Alien has run amok throughout the monastery. The landscape is ablaze, the monks try to flee, and the Abbot, drenched in blood, watches as a procession of monks are stalked through a wheat field by the Alien, which reveals itself to be chameleonic. The Alien rips through the monks “like a scythe through wheat”, and soon enough the entire field is consumed in fire. The Alien then attacks the Abbot, and we get a closer look at its camouflage abilities:

THE ALIEN

Rises out of the grass in front of the holy man.

Slowly rises up to its height of almost three meters.

Its long, smooth head is no longer black and slimy.

It is golden.

Its cable-like arms are sheathed in a straw-like covering.

It has adapted to the environment of the wheat field. Its now

grass-like lips draw back into a ghastly parody of a smile.The Abbot screams and runs.

Back to the trio, and Ripley muses on the Alien’s apparent vendetta against her. She deduces that the Alien stowed away on her EEV and killed Newt, but spared and (somehow) impregnated her as a sort of revenge. “It’s almost like he’s playing with me,” she says. “Maybe they have some sort of race memory. Maybe he knows what I did to his ‘mother’. That’s why he didn’t just kill me. That would be too easy. He has to torment me.”

They reach a corridor lined with prison cells. For some reason, Anthony is winded, and John reaches out to help him climb a ladder. Anthony suddenly experiences a vision:

He is standing in an open field, sheep grazing peacefully at his side.

Suddenly he is attacked by a horde of medieval demons.

Fish-faced demons. Man-headed bird demons.

They fly about him, grab hold of his limbs.

Anthony flails and struggles against John’s grasp, imagining that he is a demon and that Ripley, who tries to help, is the Alien. Anthony falls unconscious but quickly awakens. He explains that the visions are manifestations of all the data (specifically, medieval imagery) he has absorbed during his time in the monastery.

They eventually come across the Abbot, who is in shock over the Alien’s attack. He denounces their idea of reaching the technology room, but joins them anyway. The technology room itself is surrounded by bear traps, set to dissuade anyone from entering. Using planks of wood, the four slowly set off each trap and they approach the room.

But the Alien attacks. Anthony, in a panic, steps into one of the bear traps, and the Alien seizes him, spitting acid over his face. John manages to pry Anthony free, and they flee inside the technology room, locking the Alien outside.

Inside they find:

WINDMILLS

Real Man of LaMancha wood and cloth windmills. Two story high

arms slowly rotating. Moving enormous volumes of air through

the wind tunnel-like room. As far as the eye can see.

Turning, creaking.

WHOOSH…WHOOSH…

But no electronics. No radio. No weapons.

This is the Technology Room.Ripley collapses to the floor and loses consciousness.

She dreams that she is aboard the Sulaco. Klaxons blare and she rushes for Newt’s cryotube. Again, the Alien assaults her:

The Alien spins her – pushes her over across the sleep tube –

Like it’s taking her from behind!

Ripley looks down into the sleep tube:

Newt is gone.

Her doll’s head lays in a pool of blood.

The Alien wraps his arms around Ripley.

Thin lips pull back for a kiss.

She SCREAMS.

She awakens, back inside the technology room. There is a moment of humour:

John: I thought we’d lost you.

Ripley: What are you writing?

John: Last will and testament. (beat) Just kidding.

Ripley: Is [Anthony] –?

John: Resting. (shakes his head) He’ll be fine.

Anthony: No I won’t. He’s a terrible liar.

But the Abbot is pacing back and forth, denouncing Ripley’s actions. He accuses her of aiding the Alien. She ignores him and inspects the interior of the technology room. Everything in the colony is revealed to be reliant on plant and wind power, which is generated here. But the eco-generator is slowly destroying the wooden planet.

Ripley: Don’t you see? This is a planet set to self destruct. Not in ten minutes or two hours but soon. Your atmosphere here is finite. If the plants die the fires will eat up all the oxygen – this planetoid will be dead – Everyone will die.

The Abbot concurs, but reveals that he has always known that the environment was unsustainable. “The punishment for our crime was death,” he reveals. The monks were exiled and doomed to a slow and inexorable suffocation. “Poetic justice for the anti-technologists,” the Abbot says. “The Company’s finest work.”

The Abbot suddenly begins to talk rapid gibberish. Blood trickles from his ear and-

The Abbot’s HEAD EXPLODES!!!

Like a ripe melon dropped ten stories onto pavement.

Blood, bone, hair and brain matter SPRAY John.

John SCREAMS.A HORRIBLE ALIEN HEAD BURSTER is all that sits atop the blood spurting neck of the Abbot.

It keeps its hold on the Abbot’s spinal cord – The Abbot’s

body continues to stagger around, arms jerking mechanically as

a lack of fresh nerve impulses from the brain works its way

through the system.Ripley SCREAMS.

The Infant Alien-headed corpse stumbles towards her –

She plucks Anthony’s staff from the floor and SWINGS –

– Like a child hitting a baseball from a TEE —

WHACK-K -!!

BLASTS the Chest/head-burster across the room –It hits the floor SCRAMBLING. Scuttles down into where the

Windmills meet the floor. Disappears.

There is an obvious problem with the Abbot’s gestation time here, since he was obviously infected only hours before (if that), when the Alien wreaked havoc in the wheat fields.

Ripley becomes despondent, and is convinced that the Alien allowed the Abbot to escape with Ripley and company merely to toy with its prey. The trio briefly discuss the ‘head-bursting’ and the Alien’s reproductive process:

Anthony: Or this may be an as yet unseen stage of development – you saw a Queen – This could be like a King ant – more highly advanced than the drone, bred for survival –

John: How does this explain the thing that came out of the ewe’s chest? The Abbot’s head?

Ripley: Maybe it can deposit different types of eggs.

Ripley suddenly realises that she has been impregnated, but she does not share the news. She elects to find her ship, and Anthony decides to wait behind. Ripley and John ascend through the lower levels, and come to the satellite’s ocean, which sits in the middle of the structure.

Ripley and John spy a coracle that they can use to cross the sea. Meanwhile, Anthony, blinded by the Alien’s acidic saliva, enjoys his moments alone under the arms of the windmills inside the technology room:

The large canvas arms of the windmill rotate above his head. The wind blows through his hair.

WHOOSH…WHOOSH…

Feels good.Anthony reaches up and waves his hand over his eyes.

Anthony: Now the seer can only see what God wants him to. Forty years on a planet of Monks and I’ve finally found religion.

A floor board CREAKS. Anthony strains to hear.

Anthony: John? Ripley?

WHOOSH…WHOOSH… He knows it is not.

Anthony: Well come then. I haven’t got forever.

A shadow falls across his face. He can feel it.

He doesn’t have to see what is here.

Back in the coracle, Ripley and John discuss their personal lives. John reveals that he was condemned to the wooden world when he was still a child. He spent three decades in cryosleep at the beginning of his sentence. Ripley opens up about her daughter, Amanda, or as this script calls her, ‘Kathy’:

Ripley: She was nine when I signed on to the Nostromo. ‘Mommy will be home before you know it,’ I said. My shares would have set us up good. Then I lost sixty years floating around in a rescue pod. Thanks to the Alien. I came home to face a bitter, 70 year old woman. My daughter. A little girl whose mother never came home.

This is a strange detail, since we know that Amanda Ripley-McLaren died before Ripley was discovered. However at the time Ward’s Alien III was written the scene pertaining to Amanda’s fate had not been released: the Aliens Special Edition was some time off, and one version of Aliens’ early drafts described a scene where Ripley contacts her elderly daughter, but is shunned.

Unbeknownst to them, the Alien is stalking them underwater. They reach the upper levels and find the once-idyllic fields ablaze. Roasted corpses lie in the ash. Smoke bellows and pumps through the air. Monks have been impaled on their own spears, and their bodies are covered in cocoon resin. “Heaven has become Hell,” reads the script.

Ripley and John enter the glassworks and find Brother Kyle casually playing solitaire and talking to himself. Like the Abbot, he beings to speak gibberish. John euthanises him (via strangulation) and the two move on to the library, where they find Mattias, John’s dog, alive and well. The Alien cuts the reunion short by appearing in the doorway:

THE ALIEN

Standing in the open doorway. It’s in bad shape from the man traps.

Lost a foot. Tongue hanging out, useless.

Parts of it look like wood. Parts of it look like wheat.It carries Anthony’s waterlogged, limp body – POPS off his head like a grape from the bunch.

Tosses the corpse at Ripley’s feet.I could swear it’s trying to smile.

The Alien’s acid blood ignites on the wooden flooring, and the creature spins its tail in a circular motion, spraying and spreading fire throughout the library. The floor collapses and they plummet into the glassworks below. Ripley and John land safely, but the Alien plummets into a vat of molten glass. It begins to climb out, but:

THE HUGE DUMP TANK OF WATER

Empties a thousand gallons –

RAINS DOWN on the Alien.

It HOWLS in pain –

The Molten Glass instantly COOLS –

The rapid extreme temperature change causes the beast to

BE-THWOOOoooOOM -!!

EXPLODE into a million pieces…!!!!The room is littered with Alien bits.

Each piece is encased in glass –

Trapped like a fly in amber.

Ripley and John flee to the monastery, and enter the EEV. “Those dead monks out there are going to start hatching soon,” she warns. She readies the ship and locks John inside, announcing that she has been impregnated with an Alien spore.

Ripley: It always wins. We killed it, but it’s still inside me – You’re my last chance. If I can keep you alive it’ll make up for all those I’ve lost.

John pleads that if Ripley dies for him then his soul will be damned for allowing her sacrifice. Ripley relents, and John performs an ‘exorcism’ to expel the Alien embryo from her body. He punches and pounds her body, forcing the chestburster up into her throat. The scene is clearly sexual, with John straddling her prostate body, and when the embryo becomes lodged in her throat he leans in for a kiss and expels the Alien from her mouth – unfortunately, the creature slithers down John’s gullet to reside within his chest. He tells Ripley and Mattias to stay put, and leaves the ship.

BROTHER JOHN

Dawn’s rays are peeking through the battered ceiling as he walks slowly across the smoking roof.

Into the inferno that is the burning Abbey.Ripley watches as John and the alien horror inside him are INCINERATED.

Though she seemed unimpressed with the script as a whole, or more specifically its portrayal of her character, Sigourney Weaver read John’s sacrifice scene and had an idea – give it to Ripley. “In the original script, the male lead sacrificed himself, and Ripley goes off, again, into space,” she told Entertainment Weekly in 1992. “And I got to the end, and I thought, ‘Oh, God,’ I said, ‘This is it.'”

Back to the script, and Ripley pilots the EEV and escapes the wooden world.

She places Mattias the dog into cryosleep and spots a piece of parchment on the floor: it is John’s final testament:

John v.o.: I, Brother John Goldman of the orbiter Arceon, Minorite abbey and gaol, know the Abbot was wrong. There is a great evil here. I have seen it. I put pen to

paper now lest this plague – this creature stills my hand. I have gone down below – both to try to warn the others and get the woman -Ripley- get from her some clue as to how to battle this evil, or at least to make my peace for not defending her. She believes there is still an Earth and I hope she is right. I hope she will be able to find out. I hope she can find some rest for the devils that torment her.Ripley looks at the elapsed time counter on the command console. Pulls a pen from it’s holder. She adds:

Ripley v.o.: Whether the Earth exists or not, whether we end up in Heaven, or Hell, or the cold vacuum of space, she has.

The escape pod hurtles into the inky blackness of space, leaving Arceon burning and fading behind it like a dying ember.

THE SCREEN GOES BLACK

END CREDITS ROLL…

Teenager in the back of the movie theater shouts, “It’s in the dog!”

CONCLUSION

“Essentially I found that the whole story was being watered down, and on a project of that scale it’s very hard to maintain a single viewpoint on the material, which is kind of necessary for it to have any singularity to it otherwise it becomes a mishmash of everything you’ve seen before …

~ Vincent Ward, Venue Feature magazine, 1993.

So why wasn’t Ward’s script produced? After apparently being promised full creative control over the project, Ward found Twentieth Century Fox and Brandywine Productions beginning to reign him in. Objections were raised about the strange setting, and after one particularly patronising meeting with Fox’s executives, where Ward was made to sit on a bench outside the boardroom, the director left the movie.

The script certainly has strengths, especially with its promises of grand and nightmarish imagery, but it should be noted that almost every narrative fault in David Fincher’s Alien 3 has its genesis here: the inexplicable appearance of an egg aboard the Sulaco; the offhanded killing of Newt, Hicks and Bishop; a host of faceless and largely anonymous secondary characters; contradictory gestation times; and a general sense of confusion regarding the series’ by-now established rules.

The character of Ripley is strangely unendearing. Weaver described her as being written like a pissed-off gym coach, and that’s how she comes across. She is needlessly sarcastic in times of peril or trauma and even comes across as shallow in several excerpts. “You may dress like you’re living in the Middle Ages,” she tells the Abbot, “but you can’t treat me like your chambermaid, or whatever monks had.” Not entirely sharp in wit or intellect, and lacking any of the moral rage from the previous movie.

Brother John is a very endearing character, though it is hard to imagine Charles Dance in the role: the character has an air of naivete and boyish wonder about him, whereas Clemens is an embittered and world-weary man, a self-exile and pariah. Richard E. Grant, who screentested for the role of Clemens, may have suited Brother John more than Dance (a spectacular actor, of course). I do wish that the character survived more completely into Fincher’s movie. As for John’s dog, Mattias, it’s almost an afterthought, appearing at the opening and closing moments of the film.

Brother Kyle is unfortunately barely sketched. The script hints at a sort of teasing-camaraderie between him and John, but the character barely appears. It could be argued that the character provided the basis for Dillon, who became a far more layered and righteously-bombastic character than Kyle.

Anthony the android is an interesting character, though he violates pretty much all known rules concerning the androids so far. He tires out, is severely hindered by his wounds (unlike Ash and Bishop) and the Alien displays a strange interest in him – Ridley Scott mentioned in an interview that the original Alien would not have been interested in Ash: as an android, he was an unsuitable host. Cameron had planned a scene demonstrating this (the Aliens ignore Bishop as he crawls through the piping to the comms satellite) but it was never filmed. The Alien’s interest in Anthony also raises an interesting but unanswered question – if possible, what would an android-Alien hybrid be like? It’s an interesting angle that Ward never explores.

The idea that the Alien has a personal vendetta against Ripley is an interesting one, but its method of reproduction is hardly explained. If the Alien has a mission, it’s seemingly only to torment Ripley – a frightening idea in itself, but hampered somewhat by the Alien’s often rampage-happy attitude. There are insinuations that the orbiter will eventually become a floating hive, waiting to come across more unsuspecting prey in the vast expanses of space, but the Alien ensures the colony’s destruction by torching everything it touches. The ‘head-bursting’ is utterly bizarre, and feels like it was only included to amp up the gore factor (though it is reminiscent of the pseudacteon fly). Lastly, there is a sexual element to the Alien that is very welcome: it plays the role of father, tormentor, and rapist – which surely would have pleased fans of the original movie and admirers of the implied Lambert rape scene.

The wooden world itself would have looked strange, but fantastic. Ward was clear that the world was in a state of decay: missing panels and walls exposed the interior to the vacuum of space; the wood was knotted and gnarled and barnacled. It would have been an esoteric but very visually interesting environment for the Alien to stalk through. The prison colony in Alien 3 looks beautiful itself (Fincher made the best of a colour palette of browns and greys) but the film’s descent into a labyrinth of identical-looking corridors is a mess.

Parts of the monastery survived into the final film. Here, Ridley Scott is interviewed on the set (his son Jake worked in the conceptual department); parts of the abbey can be seen behind him.

Of the script’s various set pieces, the Alien in the fiery wheat field feels like the best. The bathroom attack seems too scatological and unbecoming of the series. Ward seems to enjoy talking about the toilet scene when he is asked about it on the Quadrilogy/Anthology, and we were clearly meant to be on the side of the Alien during its attack, since it lunges for the nasty tribunal members and the Abbot. It is similar to Superintendent Andrews’ exit in the final movie, where the Alien attack is played for a laugh as well as a shock.

Ward’s fear of studio executives muddying the creative waters was not unfounded, as the production of Alien 3 attests. The series was now a franchise, and creative liberties were becoming synonymous with financial risk.

“When you’re working in the studio system,” Ward explained, “they have these very powerful words – one’s yes, one’s no, and if you want something to retain its voice you have to know when to use the second one of those words. Also, you all have to be on the same page, because working in the studio system, it’s very corporate. One of my producers was on the same page, and one of them wasn’t. I ended up with a story credit for it, but it doesn’t at all resemble what I had in mind … These films are so expensive that the accountants start making the decisions.”

But the film did have vestiges of Ward’s story in it, which he acknowledged. “The basic story points are all mine,” Ward told The Washington Post in 1993, “but the rest is totally different. My idea was to spend $40 million recreating Bosch in space. I wanted to use every penny of $40 million just to scare the hell out of everybody. Apparently they had something else in mind.”

That same year he elaborated on his vision and the final outcome with What’s On In London magazine: “The prison planet wasn’t really me – I had more of a complete world than that. What I’d first pitched them on was, ‘Yes, it’ll scare the pants off people and yes, I can terrify them and there’ll be Aliens and yes, I can do all that stuff but I really want to create a world that’s quite special and different’ – and what they ended up doing was creating this convict world with guys with prickly scalps who couldn’t say more than ‘Der!’ I thought that was really boring – and so badly written. The characters… aaargghh!”

He was kinder when speaking with Venus feature magazine: “Under the circumstances they made a very good job. It’s not the film I would have made, but given the pressures they were under they did well.”

“David [Fincher] came in on the project when the original director Vincent Ward, who I thought was a really interesting guy, left the project. I really liked Vincent because we had already been involved in his Alien 3 and sold our company’s [Boss Effects] involvement to Vincent and 20th Century Fox. We were working with Vincent on designs and ideas when all of a sudden Vincent disappeared. Apparently he had some creative differences and so he left the project. We were really dismayed by this, because we had already been involved in Alien 3 for a couple of months … Certain parts of the monastery stayed in the movie, but got shifted around a bit. Norman Reynolds [the Production Designer] had already built numerous sets for Vincent’s script and had to start all over again. So it was kind of pandemonium.”

~ Richard Edlund.

Just as Ward read Twohy’s script and dismissed it, Fincher was not keen on filming Ward’s monastery story, and luckily for him, neither was Fox, who proceeded to redress or rebuilt the sets to resemble a prison colony.

Fincher himself was paraphrased by Alien set director Roger Christian as having walked into a meeting with Fox saying, “I don’t know what you’re doing – Alien is all about dirt and filth and oil and a hardcore technical world, why are we doing this ‘wooden’ thing?”

![Even Brett's shirt had a 'backstory': "[He] probably picked it up in some station way off, somewhere, just off Mars where they go into some gift shop. He gets cards for the kids that he'll probably see in four years time, and so he, and that's why he bought this Hawaaian shirt."](https://alienseries.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/harry-dean-stanton-alien.jpg?w=328&h=490)

!["A lot of this stuff we had to make up on the day. So we couldn't work out how to kill Ash. So we used one of those cattle prods and also left his interior to really be an organic choice, rather than having steel pipes and things like that [as innards] ... I loved the glass marbles on the strands and the teeny bits of fibre-optics, and of course his blood ... we worked forever trying to find what would be the voice of a dying robot. It's almost a doppler effect. Spooky." ~ Ridley Scott, Alien commentary, 1999.](https://alienseries.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/ashremains.jpg?w=400&h=400)