The Alien script was born in fits and starts, and was finished after a series of brainstorming and late-night writing.

Dan O’Bannon loved science-fiction, and he loved sci-fi comic books and novels. He also loved movies, especially Kubrick, Welles, and Hitchcock. More importantly, he loved cosmic horror writer HP Lovecraft. Introduced to Lovecraft at the age of 12, the story which first caught his eye was entitled The Colour Out of Space, which told of an unformed alien evil that emerges from a meteorite to suck the life from the surrounding land. Discovering an old copy of the story, O’Bannon stayed up all night reading it. Lovecraft’s concept of a wondrous but uncaring universe, and of mankind stumbling unwittingly into a horror beyond all reasoning, influenced O’Bannon’s enough that it informs and pervades his greatest and most famous work: Alien.

“I wrote the first half of Alien in 1972,” Dan told Fantastic Films magazine in 1979. The film began life as a series of notes and ideas kept in the writer’s personal notebook. “I’ve kept a running journal for about the last ten years,” he revealed. The seed which would later become Alien was first planted in O’Bannon during his experiences making his sci-fi comedy Dark Star. “It was like, while we were in the midst of doing Dark Star I had a secondary thought on it – same movie, but in a completely different light.” The aforementioned film was born from his tenure at the USC Department of Cinema, where he studied film with future horror maestro John Carpenter, who also directed the movie.

Dark Star later opened up several avenues for the budding writer/director: firstly, it introduced him to artist Ron Cobb, and then led to contact with theatre-producer-turned-wannabe-film-producer Ron Shusett, who tracked Dan down with a wish to collaborate on scripts. Dark Star’s DIY special effects also impressed George Lucas enough to get him a job creating computer screens on Star Wars; and finally, it impressed Alejandro Jodorowsky enough to have him hire O’Bannon to head up effects duties on his Dune movie adaption.

Dark Star had a bleak space setting, a rundown spaceship, a beleaguered crew, and a mischievous alien running around the ship’s halls, but it was a comedy piece without any scares – and to O’Bannon’s dismay, without too many laughs, either. Dan figured that comedy was wildly subjective; everything laughed at different things, but, he reckoned, they were all afraid of the same thing. With this notion in mind, he took his notes and began work on his horror movie. However, he hit a dead end after putting together one half of a script. Frustrated, O’Bannon relegated it to his desk drawer. The ultimate space horror film was going nowhere.

What dragged Alien back from the backburner was a meeting with future collaborator, Ron Shusett. “I went down to meet him [O’Bannon] on the USC campus, where he was living in a garret and starving, like me,” said Shusett.

He continues: “I had acquired the rights to a Philip K. Dick story, that later became Total Recall [and] Dan said, ‘Put aside your story. I want you to read something I’ve got. I’ve been working on it a year and a half. I’ve got one act. So you need a second and third act; I need a second and third act. I don’t know you so I’m not going to let you leave her with it; I’m just going to give you these 38 pages to read. I’m totally stuck, and I get nothing but shit from all anybody at film school that I’ve tried to help me lick this. If you can help me with the second and third act, I’ll help you with the Philip K. Dick story, because that’s gonna cost more. With Alien I could probably get somebody like [Roger] Corman [to finance it], because it could be done on the cheap.'”

Shusett reflected that this initial meeting with Dan would prove to be creatively and financially successful for both: “Out of that meeting – here’s two bums with no agent, no credibility, and out of that meeting came Alien and Total Recall.”

“It was only about 20 pages long, and pretty sketchy; but I remember thinking it was one of the best beginnings I’d ever had – I just didn’t know where the hell to go with it. At that time, it started with the alien transmission and the awakening from hypersleep, and went up through the discovery of the dead space captain inside the derelict. Beyond that, my ideas were kind of nebulous. I figured the crew wouldn’t get off the planetoid until the end and that the creature itself would be some sort of psychic force; but I was having trouble working it out. It was Ron [Shusett] who finally broke the ice. He brought up an old idea I’d had about gremlins harassing a B-17 bomber crew on a night mission over Tokyo and suggested I make the alien creature physical and have it stalking the crewmen on their own ship.”

~ Dan O’Bannon, Cinefex, 1979.

O’Bannon’s story had several analogues in previous sci-fi movies. Planet of the Vampires, IT! The Terror From Beyond Space, and Forbidden Planet are the most commonly cited and acknowledged influences. O’Bannon’s story also shared the spirit of Lovecraft tales such as The Nameless City, about a traveller who seeks out an ancient city that predates mankind, which ends in his demise (several Lovecraft stories follow an unwitting protagonist who falls into the clutches of a long forgotten race), and also The Statement of Randolph Carter, which details the story of two men, a professor and his aide, who investigate a subterranean lair beneath a swampland cemetery. Staying on the surface, the aide can only listen to the exclamations and terrors of the other man, who has descended below. “Alien went to where the Old Ones lived, to their very world of origin,” Dan remarked in his essay, ‘Something Perfectly Disgusting’. “That baneful little storm-lashed planetoid halfway across the galaxy was a fragment of the Old Ones’ home world, and the Alien a blood relative of Yog-Sothoth.”

A.E. van Vogt’s The Voyage of the Space Beagle has also been touted as an influence (van Vogt even litigated Twentieth Century Fox over the similarities, with Fox settling out of court) but this has been categorically denied by O’Bannon.

Initial names for the movie included There’s Someting On Our Spaceship and Star Beast, before O’Bannon settled on Alien. The title was both apt and devastatingly simple. Then, midway through Alien, O’Bannon was contacted by Alejandro Jorodowsky and hired to work on Dune. Putting Alien aside, O’Bannon left for Europe.

Though Dune would never be made under Jodorowsky, it prove to be the most critical preliminary stage of Alien’s development. During this period O’Bannon was introduced to artists Chris Foss, Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, and HR Giger. Giger and O’Bannon, two Lovecraft fans, became friends throughout the project, and at one point later in their careers, O’Bannon and Giger were even considering an adaption of Lovecraft’s work. “Dan O’Bannon, with whom I’m still regularly in touch,” Giger told Cinefantastique in 1988, “keeps telling me he would like to do Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space with me as soon as he’s able to raise the necessary funds. That could be interesting because he’s definitely one of the greatest Lovecraft experts around.”

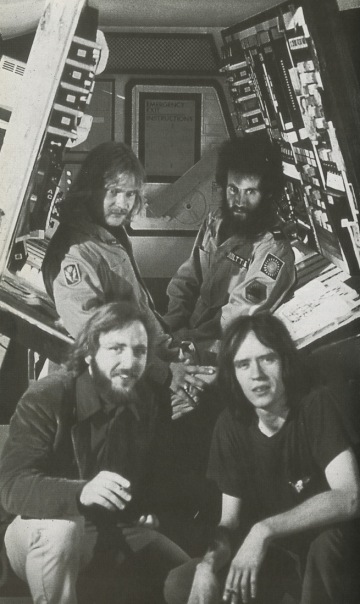

Dan and Giger at work on Alien. The artist’s visceral imagery was one major factor in compelling O’Bannon to finish the script for his movie.

O’Bannon was astounded by the sheer originality, beauty, and grotesqueness of Giger’s art. With the artist’s biomechanical phantasms running through his mind, O’Bannon knew what he needed to make his once-aborted horror film unique: a Giger monster.

“I love geniuses and have been privileged to work with several. One was HR Giger; I met him in Paris and he gave me a book of his artwork. I pored over it through one long night in my room on the Left Bank. His visionary paintings and sculptures stunned me with their originality, and aroused in me deep, disturbing thoughts, deep feelings of terror. They started an idea turning over in my head. This guy should design a monster movie. Nobody had ever seen anything like this on the screen.”

~ Dan O’Bannon, Something Perfectly Disgusting.

There were other considerations that helped Dan dust off Alien. Financially destitute after the collapse of Dune and living on Shusett’s couch, O’Bannon felt spurred to get to work on a screenplay and get himself off the sofa, and so he set to work on finishing his horror script. There were more stumbles along the way: how to get the creature off the alien world and onto the spaceship – impregnate a crewmember with an alien spore. Secondly, how to avoid the crew simply shooting the alien to death – give it acid for blood. Eventually, with the script completed, O’Bannon and Shusett began shopping their script in a bid to sell it.

“We’d finished the script,” explained Shusett, “and Dan said, ‘Let’s go to Roger Corman.’ We made an appointment; he was out of town. We saw his top guy, who said, ‘I love it! How much do you need?’ We said $750,000. We never doubted that it could become a classic. We were thrilled he was going to give us the money.”

Alien came perilously close to becoming a full-fledged B-movie with a shoestring-budget and B-grade actors and effects. More likely than not, this version of the film would have been forgotten shortly after release. Though O’Bannon and Shusett were happy to have their script handled this way, they were soon to come across even greater luck.

“Before we could sign the contract with Roger Corman,” explained Shusett, “Dan and I were walking down the street, and he saw a guy from film school named Mark Haggard. Dan said, ‘I want to ditch this guy. He’s always telling me he can make money to make movies, but he never has yet.’ We ran across the alley, but he called, ‘Dan, Dan! I hear you got this great script! Can I read it?’ We said, ‘Sure, everybody else is reading it.’ We were too stupid to think anyone would rip it off because we didn’t think it was good enough. He called the next day: ‘I got the money to make it.’ We said we had the money to make it with Roger Corman. He said, ‘I can get it made at a studio.’ We said, ‘We can’t sit around tying this up, waiting on the studios.’ He said, ‘No, twenty-four hours – that’s all I need. I’ll only go to one place. Let’s draw up a piece of paper and figure out what I get if I get you the money – my position and what my fee is.’ We said okay.”

Haggard’s connections in the movie industry included Walter Hill and David Giler, of Brandywine Productions. Haggard told O’Bannon and Shusett that he knew of “two hot writers,” but the catch was that “they can’t write science-fiction.” He continued telling the two that “They’ve got the confidence of [Fox executive] Alan Ladd, Jr. They’re partnered with a producer who’s won an Oscar, Gordon Carroll, who produced Cool Hand Luke. They want to do the dark side of Star Wars. They’ve read fifty scripts, and they can’t write one themselves because they don’t know how to do science-fiction, although they’re both successful writers.”

Shusett and O’Bannon weighed up their options. “[Walter Hill] wrote The Getaway, the Sam Peckinpah version,” said Shusett, “and he was becoming a hot director; he had done Hard Times with James Coburn; [David] Giler wrote the original Fun With Dick and Jane. So it was a natural marriage. They had the clout, and they loved the script.”

“They read it,” O’Bannon told Fantastic Films, “they called us in and Gordon [Carroll] said to us, ‘We’ve read 300 scripts and this is the first one we’ve all agreed on.’ Okay, great compliment. And they proceeded to make a deal with us. And we got into a lot of haggling, there was at least a month of negotiating. Finally we made a deal, an option deal, and they took it to Fox with whom they’d just made some kind of production arrangement for their company. And Fox immediately expressed interest and Brandywine exercised the option, which was a real surprise ’cause it was the first time in my life I’d ever had an option exercised.”

Walter Hill told Film International in 2004 how he came across Alien‘s script. “David [Giler] and I had formed a production company with Gordon Carroll – this was about 1975. About six months after we started, I was given a script called Alien by a fellow I knew, Mark Haggard, who was fronting the script for the two writers. I read it, didn’t think much of it, but it did have this one sensational scene – which later we always called the ‘chestburster’.”

Hill mulled over the script, and approached Giler with an idea: take O’Bannon’s script, and rewrite it to suit an A-level feature film. “I gave it to David with one of those, ‘I may be crazy, but a good version of this might work’ speeches. The next night, I remember I was watching Jimmy Carter give his acceptance speech to the Democratic Convention [July, 1976] and was quite happy to answer the phone when it rang. It was David – he told me I was crazy, but he had just got as far as this scene [the chestburster] and it was really something.” Though Giler has been adamantly dismissive of Dan O’Bannon’s script over the years, Hill always acknowledged the script’s strengths: “There was no question in my mind that they wanted to do a science-fiction version of Jaws,” he said. “It was put together with a lot of cunning. To my mind, they had worked out a very interesting problem. How do you destroy a creature you can’t kill without destroying your own life-support system?” Hill also compared O’Bannon’s story to another classic: “I should probably also say that The Thing (1951) was one of my favourite films from when I was a kid, and this script reminded me of it, but in an extremely crude form.”

On the other hand, Giler trashed both the script and O’Bannon, telling Cinefantastique in 1979 that, “[the script] was a bone skeleton of a story then. Really terrible. Just awful. You couldn’t give it away. It was amateurishly written, although the central idea was sound. Basically, it was a pastiche of fifties movies. We -Walter Hill and I- took it and rewrote it completely, added the Ash and the robot subplot. We added the cat Jones. We fleshed it out, basically. If we had shot the original O’Bannon script, we would have a remake of It! The Terror From Beyond Space … It wouldn’t surprise me at all to learn that O’Bannon stole the idea [for the film], I must tell you,” (contrary to Giler’s claim, the ship’s cat was present in O’Bannon’s script.)

Hill was unfazed by Giler’s low opinion of the material, and opted to rewrite the script. “I said I’d give the fucker a run-through. David was going off to Hong Kong with his girlfriend, but before he left we thrashed it out pretty good.”

The ‘revised final’ script was actually put together after filming had ceased, and incorporated the ad-libs and changes wrought on the film by budget and practical logistics.

There were several things that Giler and Hill immediately wanted to change. First, they disliked the names O’Bannon had bestowed on his characters. Names like ‘Melkonis’ and ‘Faust’ were a little too strange, they decided, and so they picked out new monikers with a more Earthly bent. “Some of the characters are named after athletes,” revealed Hill. “Brett was for George Brett, Parker was Dave Parker of The Pirates, and Lambert was Jack Lambert of The Steelers.” As for the ultimate survivor, Roby, “I named her Ripley, after Believe it or Not. Later, when she had to have a first name for I.D. cards, I added Ellen (my mother’s maiden name).”

Secondly, they wanted to remove all of the extraterrestrial elements from the screenplay. Giler explained that, “We believed that if you got rid of a lot of the junk -they had pyramids and hieroglyphics on the planetoid, a lot of von Daniken crap, and a lot of bad dialogue- that what you would have left would be a very good, very primal space story.”

Other Ideas: “Regarding Giler and Hill, they did eight various drafts,” explained Ron Shusett, “And they went off in many different directions … They were trying, roping, you always have to see how far you can push the envelope. It got ridiculous when you got Genghis Khan to fight the Alien … Their idea was somehow every past villain in history they would have to fight, somehow, Attila the Hun, ah, you know … famous historical villains … Hitler-type people, people that were mass murderers, or in some cases maybe a creature … Jack the Ripper, well that was one of them.”

The pyramids and hieroglyphics they replaced with government installations and weapon testing grounds. These elements themselves would later be vetoed by Ridley Scott at the behest of O’Bannon and Shusett. “They wanted that to be an army bunker for some reason,” said Shusett. “I guess they just went, ‘Okay this will give it realism,’ and that’s boring. You can’t, you know, once you’re committed to [Giger], you can’t go back to a steel twentieth century army bunker. That goes backwards in imagination, whereas that Giger design which he hand painted, airbrushed that whole wall himself personally, like he did his artwork, and that’s why it looks so eerie.”

Dan was likewise abhorred by the direction the producers were taking the film, and approached Ridley about the alterations. “I went in,” said O’Bannon, “and there [Ridley] was. Ronnie Shusett had feverishly rushed up to him and shoved a copy of the original draft of the script into his hands because Hill and Giler had begun to rewrite it. We were disturbed by the content of the rewrite. Ridley read it and went, ‘Oh yes. We have to go back to the first way. Definitely.’ So it was Giler and Hill’s turn to be disturbed. As a result, the entire remainder of the production became a battle between camps. One camp wanting one version of the film and another camp wanting the other version.” Scott settled on the pyramid and alien angle, but ultimately these were either scrapped or merged due to time or budget limitations.

Thirdly, shortly after Scott’s recruitment, Alan Ladd Jnr suggested that they have a woman on board the Nostromo. Ladd asked O’Bannon and Shusett for their opinion: both agreed it was a good idea, after all, their script carried a unisex tag for their cast.“Having pretty women as the main characters was a real cliché of horror movies,” O’Bannon told Cult People, “and I wanted to stay away from that. So I made up the character of Ripley, whom I didn’t know was going to be a woman at the time … I sent the people of the studios some notations and what I thought should happen and when we were about to make the movie the producer [Walter Hill] of the film jumped on it. He just liked the idea and told me we should make that Ripley character a woman. I thought that the captain would have been an old woman and the Ripley character a young man, that would have been interesting. But he said, ‘No, let’s make the hero a woman.’” Giler and Hill then rewrote their already-rewritten screenplay to accommodate this idea. “David had suggested making the captain a woman,” said Hill. “I tried that, but I thought the money was on making the ultimate survivor a woman.”

Fourth, feeling that the ship computer’s role would be perceived as being too akin to that of HAL9000 in Kubrick’s 2001, Giler and Hill, who had toyed with fusing the computer with Company-driven malevolence, transposed this idea to a new member of the crew – Science Officer, Ash. In addition to making him duplicitous, the two also decided to make him inhuman; an idea that Hill attributes to Giler. “He’s got a marvellous capacity for coming up with the unexpected – a u-turn that’s novel but at the same time underlines what you’re trying to do. A lot of the time he’ll present it as a joke, , and it’ll turn out to be a great idea. Like in Alien, when the Ian Holm character was revealed to be a droid – that was David.”

On the other hand, Giler attributed the genesis of the idea to Hill: “Walter Hill and I were writing the script,” he told Fantastic Film, “and we had invented the subplot of this dodging character. And Hill said, ‘I have what I think is a dreadful idea or a really good one. What do you think of this? Suppose , in this part, whack!, his head comes off and he’s a robot?’ ‘Well terrific,’ I say, ‘let’s do that. And we’ll put it on a table and then we’ll have the head talk.’ So we went back and made the subplot work for that. Actually at one time I wanted the first words from the robot on the table to be the Kipling poem, ‘If you could keep your head all about you…'”

The android Ash sneaks up on Ripley within Mu-th-r’s control room. The malignant android and Company were inventions of Giler and Hill.

The android twist was apparently met with skepticism by O’Bannon and Fox, but Ron Shusett stuck up for the idea. “While we were at [20th Century Fox], Giler and Hill, who were my co-producers, came up with this idea and wrote it into the script,” explained Shusett. “Everybody hated it but me. The studio was afraid of it. Dan said, ‘I don’t like it.’ Their own partner said, ‘It’ll be a mish-mosh.’ I said, ‘Let’s film it and preview it.’ I thought it was a brilliant concept and it gave a resonance to everything that came before, because you think back to when Ash opened the door and let the creature on board, you realize he wasn’t human, so of course he could have the lacking of humanity to sacrifice all the humans as long as he saved the Alien. That gave it an underbelly that helped it last through the years. When we filmed it, we weren’t sure it would work. We tried it on an audience, an invited audience. That was the only way that everybody said, ‘Oh, you need that.’ … I saw it at a preview in Dallas: when that robot’s head came off, an usher actually fainted!”

O’Bannon on the other hand remained indignant that Ash added nothing to the film’s plot. Riled by Giler and Hill’s changes to his script, he stuck his neck out and remained antagonistic towards the pair. Whilst this worked to return the alien elements that Giler and Hill had initially exercised, and whilst it also allowed for Giger to be brought onto the film (to the initial chagrin of the producers), O’Bannon’s forcefulness resulted in him being removed from the shoot.

“And boy, believe me, I was inextricably involved [with Alien], because if there was any way they could of gotten me out of their hair they would have, ’cause I was such a thorn in their side. I remember being faced with what I call a moral decision. My agent, my manager, and everybody else was starting to go over to England to start working on the film proper, and they said, ‘Be sure not to antagonize anybody, ’cause they’re so important, it’s your first project and it’s a major studio, every body’s liable on you to be friends.’

I got over there and I found that the confusion was so great and the babble of voices was so loud that I couldn’t make myself heard without being obnoxious. I couldn’t make an impact and there were things I felt so strongly about that i wanted to have heard. I wanted to win points, certain points I felt very strongly about. So I finally decided, ‘All right, I’m going to go against the good advice for my career; I’m going to fight.’ And my reasoning was, in 40 years I’d still be able to sleep with myself. That I wouldn’t look back and say, ‘You know, there’s Alien and it stinks and if I had fought, maybe it wouldn’t.’ And I looked forward to that in my own frame of mind. And I decided, ‘All right, I’ll fight,’ even though that it’s tactically the wrong thing to do.”

~ Dan O’Bannon, Fantastic Films, 1979.

O’Bannon revealed that before the film went into production David Giler “left for mysterious reasons” and apparently having left script rewrites unfinished. “And finally at the last minute, I saw that everyone, including Ridley, was so fed up with Giler and Hill’s failure to make any of the promised revisions that they said they were gonna make, that a little sliver of opportunity was created. I was standing there, I said, ‘You know, I’ll fix it if you’ll let me.'”

“When they bought the script and took it away from me to make it themselves, they tried to inflate it beyond what it was,” O’Bannon told Starlog in 1983. “Hill and Giler did nine rewrites, each progressively worse. They said, ‘You have a spaceship, it’s gonna be the biggest spaceship in the universe’. And then they changed that, and wanted a fleet of spaceships. I said, ‘Just one monster?’ They said, ‘Not a monster, we’ll have fifty monsters!’ It finally reached a point that Alien was in such bad shape that it couldn’t be filmed.”

“There were two weeks of frantic mutual work between all of us,” O’Bannon continued, “trying to put the script into a shape that they liked. By the time we got done, it was maybe 80% of the what the original draft was. What we got on the screen was actually very close to the original draft.”

Ron Cobb stold Starburst magazine that “The whole film is in a constant state of flux. Script revisions are going on every day. Things that haven’t been shot are still being rewritten and that’s why Dan is feeling better, because he and Ron Shusett are having substantial input into these last minute script changes. They’re fixing it quite well, strengthening it considerably.”

Here is a breakdown of the two plots. Giler and Hill’s version is a summary of their script before O’Bannon and Shusett urged Ridley Scott to have the script revised.

Dan O’Bannon’s Alien, a synopsis: the crew of the commercial vehicle ‘Snark’ awaken from cryosleep on a return voyage to Earth. Their ship’s computer has detected an SOS beacon of unknown origin emanating from a nearby planetoid. The crew land, and find a derelict spacecraft containing the corpse of a dead alien pilot. Nearby they find another structure; an ancient pyramid, containing mysterious spore. One of them is attacked and impregnated; the creature erupts during a meal after the ship has continued its journey to Irth. The crew are picked off one by one until only Roby survives, along with the ship’s cat. The Alien is ejected from the emergency shuttle and vapourised. The Snark itself is destroyed. Roby enters cryosleep for the journey home.

Walter Hill & David Giler’s Alien, a synopsis: the crew of the commercial vehicle ‘Nostromo’ awaken from cryosleep on a return voyage to Earth. Their ship’s computer has detected an SOS beacon of unknown origin emanating from a nearby planetoid. The crew land, and find a derelict spacecraft containing the corpse of a dead human pilot. Nearby they find another structure; a concrete Cylinder, containing mysterious spore. One of them is attacked and impregnated; the creature erupts during a meal after the ship has continued its journey to Earth. The crew are picked off one by one, and the Science Officer Ash is revealed to be a Company robot. Ash reveals that the crew were led to the Cylinder deliberately, to serve as test subjects for the weapons division – the Alien is one of the Company’s bioweapons. In the end, only Ripley survives, along with the ship’s cat. The Alien is ejected from the emergency shuttle and vapourised. The Nostromo itself is destroyed. Ripley enters cryosleep for the journey home.

As already pointed out, O’Bannon and Shusett intervened to have Hill and Giler’s draft rewritten to incorporate the alien elements that they had excised. “Ridley read [the original script] and went, ‘Oh yes. We have to go back to the first way. Definitely.'” Though Giler and Hill acquiesced to Scott’s demand, they still managed to infuse the script with the paranoia of a Big Brother corporate entity whose sheer size and oversight leads to the deaths of its employees in some dark corner of space.

At a first look, the most noticeable change between the two scripts is not so much the content, but the stylistic differences between O’Bannon and Walter Hill, whose sparse prose style is indelibly stamped on Alien‘s shooting script. The two writing styles are completely dissimilar. O’Bannon writes in a pulp fashion that reflects his comic book roots. Walter Hill however writes in a restrained and low-key tone. “I tried to write in an extremely spare, almost haiku style,” Hill said of his method in 2004. “Both stage directions and dialogue. Some of it was quite pretentious – but at other times I thought it worked very well.”

Style aside, the actual overall content of the rewrite remains almost unchanged, even in the final draft. Many character beats remain, but are transposed to different characters. Many devices and set-pieces remain. Dialogue is clipped in the revisions, but retains much of its content (though it’s much sharper in the revisions). Dialogue often finds itself hopping from mouth to mouth throughout the various revisions; speech that belongs to Melkonis/Lambert in the O’Bannon draft is transposed to Dallas in the Giler/Hill draft – and then shifted to another character in the final film. For example:

MELKONIS: I never saw anything like that in my life … except maybe molecular acid.

HUNTER: But this thing uses it for blood.

MELKONIS: Hell of a defense mechanism. You don’t dare kill it.

ASH: I’ve never seen anything like that, except molecular acid.

BRETT: This thing uses it for blood.

ASH: It’s the asbestos that stopped it, otherwise it eould have gone straight through.

DALLAS: Wonderful defense mechanism. You don’t dare kill it.

The dialogue above remains pretty much the same in the film, but the speech is attributed to a different character, (the asbestos line is removed completely ) Though Giler and Hill changed much, a lot of the text actually remains virtually unchanged from the original. Here is a scene from the Giler and Hill rewrites, followed by the same scene from O’Bannon’s script:

Carefully, Lambert advances down the passageway.

Then the Alien steps out from behind Parker. Picks him up.

Parker screams.

Lambert whirls around. Sees the thing dangling Parker.

PARKER: Use it. Use it. God, use it.

LAMBERT: I can’t!

The Alien takes a bite out of Parker. He screams, writhes.

Lambert can stand it no longer. She raises the flamethrower and fires.

The creature swings Parker around as a shield. He catches the full blast.

Lambert instantly releases the trigger mechanism. But Parker is now a kicking ball of flame. Still held at arms length by the Alien.

Carefully, Standard advances down the corridor.

Then THE CREATURE POPS OUT OF HIDING BEHIND HUNTER, AND PICKS HIM UP.

Hunter screams.

Standard whirls around, sees the thing clutching Hunter.

HUNTER: The flamethrower!

STANDARD: I can’t, the acid will pour out!

At that moment the Creature TAKES A BITE OUT OF HUNTER, WHO SCREAMS IN MORTAL AGONY.

Standard can take it no longer, he raises the flamethrower and fires.

BUT THE CREATURE SWINGS HUNTER AROUND AS A SHIELD AND HUNTER CATCHES THE FULL BLAST OF THE FLAME.

Standard instantly stops firing, but now Hunter is a kicking ball of flame, held out at arms length by the monster.

The above example describes a scene that is drastically different from the events that unfold in the film. Here is an example featuring a conversation between Dallas, Ash, and Kane that is present in both scripts and the film. Again, Giler and Hill’s version is up first, followed by O’Bannon’s dialogue:

ASH: Mother says the sun’s coming up in about twenty minutes.

DALLAS: How far from the source of the transmission?

ASH: Northeast … about 3000 meters.

KANE: Close enough for a walk.

DALLAS: Let’s run an atmospheric.

ASH: 10% argon, 85% nitrogen, 5% neon … I’m working on the trace elements.

DALLAS: Pressure?

ASH: Ten to the fourth dynes per square centimeter.

KANE: I volunteer for the first group going out.

MELKONIS: Well … (consults instruments) … this boulder rotates every two and a quarter hours. Sun should be coming up in about 20 minutes. Transmitter … is to the northeast … about 300 meters.

BROUSSARD: Not bad for a walk.

STANDARD: Roby, will you run me an atmospheric please?

ROBY: 10% argon, 85% nitrogen, 5% neon … some trace elements … looks alright. Safe enough. No moisture.

STANDARD: Temperature?

ROBY: Is bracing hundred and twenty degrees cooler outside. Ten to the fourth dynes per square centimeter.

BROUSSARD: I volunteer. For the expedition.

Such observations make us question David Giler’s claim to Cinefantastique that “We changed all the dialogue. Every word of it. Nothing is left of O’ Bannon’s draft. Not a word of his dialogue is left in the film.” Not just the dialogue, but the descriptive action in the Giler and Hill script bares much in relation to O’Bannon’s:

Dallas, Kane and Lambert enter the lock. All wear gloves, boots, jackets. Carry laser pistols. Kane touches a button. Servo whine. Then the inner door slides quietly shut. The trio pull on their helmets.

Standard, Melkonis, and Broussard enter the lock. They all wear surface suits with gloves, boots, jackets, and pistols. Broussard touches a button and the inner door slides shut, sealing them into the lock. They pull on rubbery full-head oxygen masks.

Of Giler and Hill’s dialogue polish, O’Bannon remarked, “I think they made some of the characters cuter than they were. Some of the dialogue is definitely snappier than it was in the original draft.”

Trouble arose when it came to screenplay credits. According to O’Bannon on the Alien Anthology, the film’s credit originally went solely to Walter Hill and David Giler. When O’Bannon called Hill to discuss the credit and suggested it include all of their names, with O’Bannon’s name being prominent (considering he was the original writer) Hill rebuked the offer and decided to stick with the WGA’s initial Giler/Hill decison, with O’Bannon entirely uncredited. O’Bannon detailed the fight to reinstate his name in the credits:

“Back in September or so last year I started negotiating and hassling for my screen credit. Giler and Hill wanted credits to read; Screenplay by Walter Hill and David Giler based on a screenplay by Dan O’Bannon from a story by O’Bannon and Shusett. They didn’t shoot the Giler and Hill rewrite, Ridley shot my script. So I took it to the writer Guild for arbitration. On a Friday I get this call from the WGA telling me that they’ve decided in my favour. Then in the next breath they tell me Hill had immediately submitted an appeal of that decision. Finally after months and months of hassle the WGA has decided and the writing credit will read: A screenplay by Dan O’Bannon from a story by Dan O’Bannon and Ron Shusett. I’ve been vindicated. I still don’t know about my design credit but we’ll see. The problem with the money-men is that a lot of them don’t care about making good films, and don’t understand movies, yet they insist that you do it their way.”

~ Dan O’Bannon, Fantastic Films, 1979.

Despite Dan’s protestations, the Alien we know is almost certainly a compromise between the differing visions that O’Bannon and the producers had. Rather than resulting in a chaotic narrative mess, the film-makers managed to tease out a taut, lean, consistent horror movie that is infused with both Lovecraftian undertones and an unintrusive corporate conspiracy plot.

Despite this success, feelings between the two producers and O’Bannon remained mutually strained following the debacle of writing and crediting the film. “Walter Hill and David Giler, who have been attached to the project from the beginning, they hate my guts,” O’Bannon told Den of Geek in 2007. “Because they’re scoundrels. They thought that by pulling a couple of fast ones that they could steal my screenplay credit from the original Alien. They should have had enough experience themselves to know that that wouldn’t work, because they both had a couple of studio pictures already in their background, and they were both Writer’s Guild members, and they had been through arbitrations.”

“The arbitrations standards are pretty clear, and they should have realised that no minor changes were gonna get them – certainly not the sole screenplay credit, which they expected, and in fact they ended up getting no screenplay credit. I don’t know – villains think as villains think; y’know – they’re stupid. When they failed to get that credit they both just flipped their lids. They’d already targeted me as a victim, meaning that I was ‘not a friend’. And then when the victim ended up not being victimised, they were just furious, just beside themselves. Walter Hill spent several years telling everybody who would listen, any journalist that he’d really written Alien and I stole his credit, until I finally got fed up and had my lawyer shut him up for good.”

“Well, David Giler, who is one of the producers, sat down and just kept rewriting it all. Just kept rewriting and rewriting it, and rewriting it, until there was very little resemblance to the original screenplay. I wasn’t allowed to participate in that because he didn’t want me to. He was producer.

Then two weeks before we started shooting, he left for mysterious reasons. He left the production. The main producer, Gordon Carroll, and the director called me in and there were two week of frantic mutual work between all of us trying to put the script into shape. By the time we got done, it was maybe 80 percent of what the original draft was. What we got on the screen was actually very close to the original draft.”

~ Dan O’Bannon.

Ron Cobb also spoke of Dan’s last-minute difficulties with turning Giler and Hill’s constant revisions into a tighter and more tonally consistent film. “I think that the real problems were in Dan’s sphere,” he said in 1979, “because of what they did with the rewriting. It’s terrible, sloppy revisions, some of them pointless. It was very difficult for Dan to tighten the thing back up to keep it consistent and have it make sense.”

“In the end,” summed up Giler, “the plot in O’Bannon’s Alien and the one in ours are the same. Basically the same. And yet, they are as different as night and day. It’s something subtler than the Writer’s Guild is equipped to handle. Though the storylines are basically the same, what happens to the characters has been changed drastically. That is what has been altered.”

What is meant by the caption: “The ‘revised final’ script was actually put together after filming had ceased,[…]” Does this mean to imply that the date June 1978 on the script front page is not correct since as I understand filming went from july until december 1978?

The ‘revised final’ script is dated December 1978. I will dig up other screencaps, (I have a plethora of the film’s various scripts on my hard drive.) Things like Ash’s death speech were written the day they were filmed, and so different versions of them appeared in other scripts.

Give me some time and I’ll go through the scripts and how they’re dated, since my memory on the matter isn’t up to scratch lately (blame university…)

I am fascinated by the evolution of the scripts and did not know there was one dated December 1978. The lastest I’ve found has a hand-written revision date on the cover page of October 4, 1978. Would love an hour with Scott’s copy and a scanner…LOL!

Pingback: Ridley Scott’s Alien II (or ‘What He Wanted to Happen’) | Strange Shapes

Pingback: Crew Logs: Dan O’Bannon | Strange Shapes

It is a shame no one has gotten a hold of the various Giler and Hill scripts. There are excerpts from one of the Hill/Giler scripts where Mother was the secondary villain, not Ash. They essentially wrote in the more exciting “HAL versus Bowman” scene from the book 2001, where Mother is venting the air out, exploding hallway panels in Ripley’s face, as she’s trying to crawl down a tunnel to access Mother’s brain, which she proceeds to stab with a screwdriver as it spews purple fluids all over her face.. all the while Mother is cussing her out.

There are excerpts from this script in the Cinefantastique magazine dedicated to ALIEN.

I’d love to see this. Never managed to get a copy of that Cinefantastique issue (money!)

I’m reading that issue right now (Did you get my email Valaquen?) and its fascinating. Walter Hill has the mother computer getting pissed off and screaming, shooting tracer bullets at Ripley and calling her a cocksucker! Hill is a great writer, but I dont think he does science fiction. 🙂

And either one or both of the guys writing the article seem like schooks. I guess becasue they got an interview with Hill for the magazine that they felt beholden to go out of their way to use any flimsy excuse to shit on Dan O’bannon. They condemn Dans script for being too wordy (…and too macho, too juvenile and too unacceptable…), and then share Hills version where the foul mouthed gun toting mother computer goes on for a full page describing natures laws of natural selection while Ripley keeps repeating, “Enhance. Enhance some more. Enhance.”

Fascinating stuff though

They include a good little chunk of a script that isn’t available on the internet.

Pingback: Was Jack the Ripper Somehow Going To Be In the Original Alien Movie? | HE'SHero.com

Great post!